Original Author: Unintelligible sol (X: DtDt 666)

In this wave of spike-style decline, many brothers say that Binance's market makers have encountered problems, including the pegged gold $PAXG which also spiked.

Why do many retail investors say that every time they buy, the price drops, and every time they sell, the price rises?

So, what do market makers do? How do they operate?

Fee rebates

Bidirectional orders, where both sides are executed, earning a small profit from the spread, accumulating thin profits, essentially capturing liquidity through time and information delays.

Price discovery, helping the market to price efficiently and providing liquidity.

Market manipulation, coordinating with news to sell liquidity to retail investors.

The English term for "做市商" is Market Maker, which means: in places where there is no market, market makers create a market.

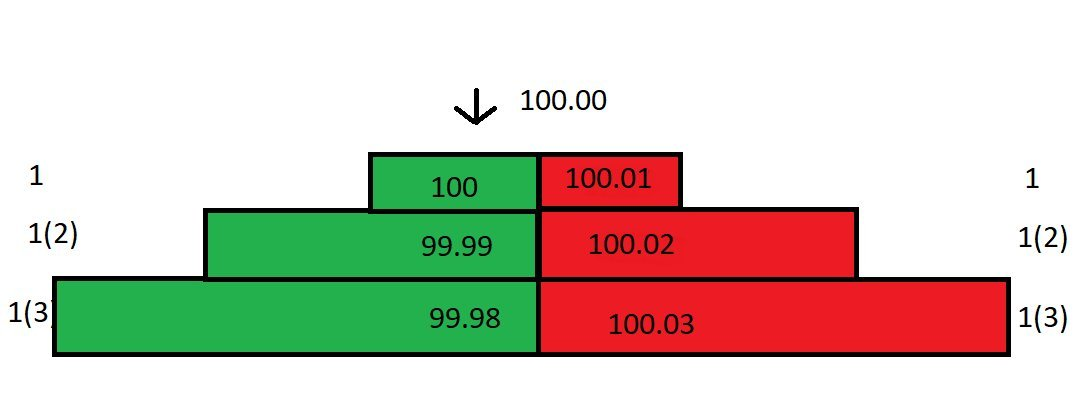

First, let's assume you are a market maker for a project, and now there is an order book that looks like this:

Let's make some assumptions: there are no other investors placing limit orders in this market, you are the only liquidity provider, meaning you are the only market maker; the minimum price movement unit is 0.01; all takers need to pay a 0.025% fee, and all makers receive a 0.01% rebate.

As a market maker, you are on the side of the limit orders, and for all market orders that execute at your price, you can receive a 0.01% rebate.

The difference between the best buy price and the best sell price (best bid and best offer, abbreviated as bb/o) is called the spread, and the current order book's spread is 0.01.

Now, a market sell order comes in and will execute at your buy price of 100. You paid 100 for this transaction, but the other party actually only received 100 - 0.025 * 100 = 99.975, where 0.025 (100 * 0.025%) is the fee, and you can receive a 0.01% rebate from it, so you actually only paid 99.99.

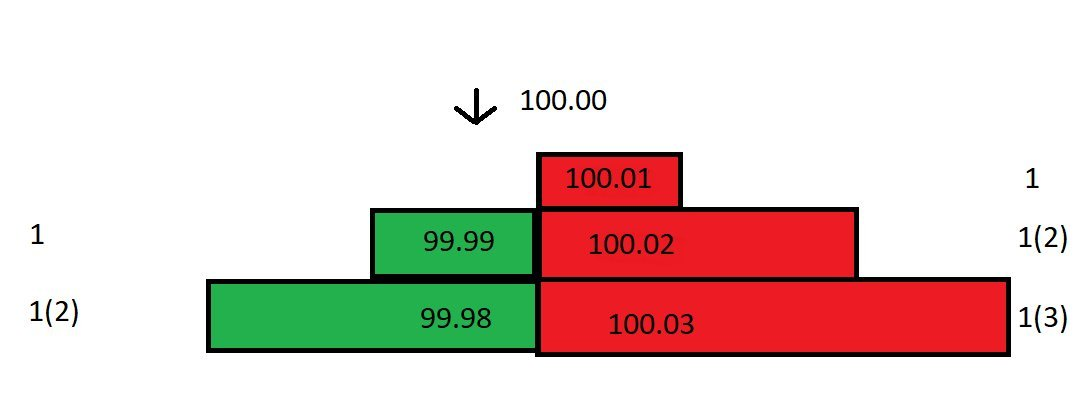

Since the buy price has been taken, the structure of the order book has changed, and the current spread has become 0.02. However, the market price is still 100, because this is the last transaction price:

If a buy order comes in at this moment, it will execute at your sell price of 100.01. You bought the previous order at 99.99 and are now selling at 100.01, earning 0.02, plus the rebate, the total profit from this buy and sell can reach about 0.03.

Although your buy (100) and sell (100.01) spread is only 0.01, the actual profit is as high as 0.03!

If a continuous stream of market orders comes in and executes with you, you can earn 0.03 on each buy and sell, accumulating wealth in no time!

But unfortunately, the market did not develop as smoothly as you expected. After you received the goods at 99.99, the spot market price immediately dropped from 100 to 99.80. You quickly canceled your buy orders at 99.99 and 99.98 to avoid being arbitraged by others.

Since the current price has dropped to 99.80, your sell price is still 100.01, which is too high, and no one will execute with you at that price. Of course, you could lower your sell price to 99.81, but that would result in a loss of 0.17.

Don't forget, you are the only market maker in the market, and you can fully utilize this advantage to adjust the order book and minimize losses!

You calculated what price to set your sell order to break even. You received the goods at 99.99 and want to sell at a break-even price, so your sell order should be at 99.98 (because with the rebate, you actually receive 99.99, which is just enough to break even).

So you adjusted the order book, placing buy orders at 99.80 and 99.79, and a sell order at 99.98:

Although the price difference is now large, you are the only market maker in the market, and you can decide not to lower the sell order price. If someone is willing to execute at the sell price of 99.98, that would be great. If not, that's okay, because your buy order price has been lowered to 99.80, and a market order will come in and execute with you.

At this point, a market buy order comes in and executes at your buy price. Now you have 2 contracts, and the average holding cost will be spread to: (99.79 + 99.99) / 2 = 99.89. (The previous transaction was at 99.99, and this one at 99.79, executed at a lower price than the buy order due to the 0.01% fee rebate.)

OK, now the average holding cost has been reduced to 99.89, and you lower your sell price from 99.98 to 99.89. Suddenly, the huge price difference has halved. Next, you can continuously operate in this way to gradually reduce costs and narrow the spread.

In the above example, the price only fluctuated by 0.2%. What if the price suddenly fluctuates by 5%, 10%, or even more? Even using the above method could lead to losses because the spread is too large!

Therefore, market makers need to study 2 questions:

How much volatility is there in price over different time windows?

What is the size of the market's trading volume?

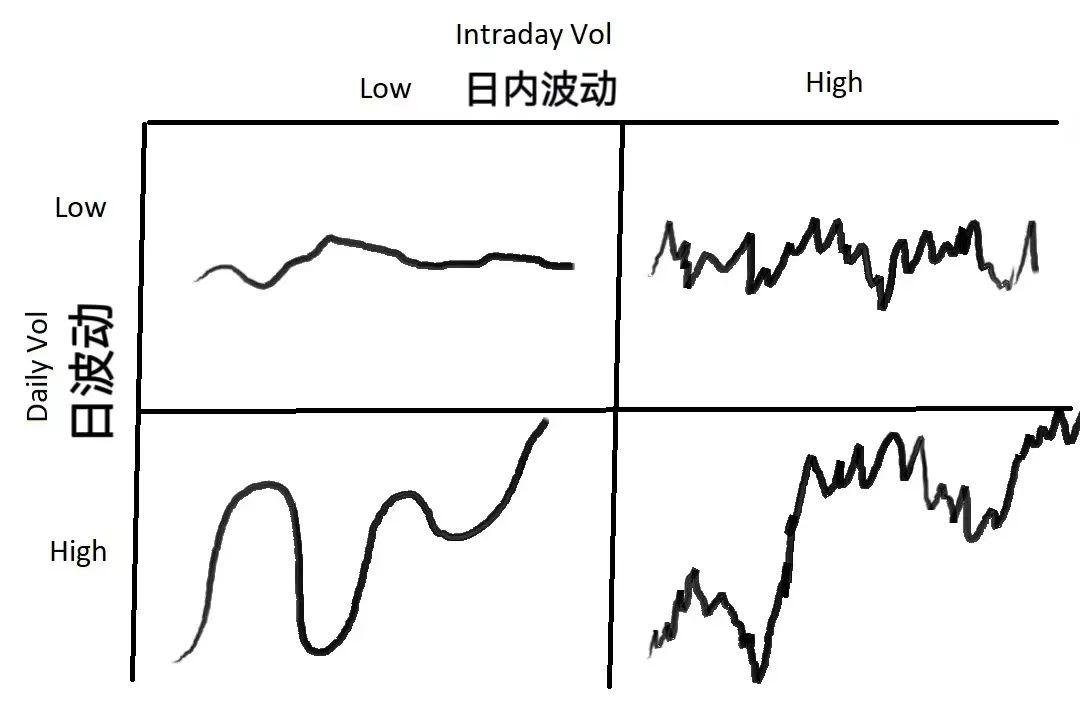

Volatility simply refers to the degree of deviation of the price from its average. The volatility of prices varies across different time windows. A particular asset may fluctuate wildly on a 1-minute candlestick chart while showing a calm trend on a daily chart. Trading volume indicates liquidity, which affects the spread of limit orders and the frequency of transactions.

The above chart demonstrates 4 types of price volatility. For different volatility situations, market makers need to choose different response strategies:

If the overall market volatility is low, with both daily and intraday volatility being very low, then a smaller spread should be chosen to maximize trading volume.

If daily volatility is low but intraday volatility is high (meaning prices fluctuate significantly but without substantial changes), you can widen the spread and use larger order sizes. If prices move unfavorably, you can use the method mentioned above to lower the average cost to reduce losses.

If daily volatility is high but intraday volatility is low (in other words, prices are moving steadily in a trend), you should use a smaller, tighter spread.

If both daily and intraday volatility are high, you should widen the spread and use smaller order sizes. This is the most dangerous market situation, often scaring away other market makers, but it also contains many opportunities. Most of the time, market makers earn stable profits, but when the market behaves erratically, it can breach one side of your order book, forcing you to incur losses.

Market making has 2 key steps: determining fair price (pricing) and determining spread.

The first step is to determine fair price, which is to identify at what price to place orders. Pricing is the first and very important step; if your understanding of fair price is too far off, your "inventory" may not sell, and you will ultimately have to close your position at a loss.

The first method of pricing is to reference the price of the asset in other markets. For example, if you are trading USD/JPY in the London market, you can refer to its pricing in the New York market. However, if there are abnormal fluctuations in prices in other markets, this pricing method can become very unreliable.

The second pricing method is to use the mid price, where mid price = (best buy price + best sell price) / 2. Using mid price for pricing is a seemingly simple but very effective method because the mid price is the result of market competition. Quote around mid, the market is probably right; pricing around the mid price means the market is likely correct.

In addition to the 2 pricing methods mentioned above, there are many other pricing methods, such as algorithm-based pricing and market depth-based pricing, which will not be elaborated on here.

The second question market makers need to consider is the spread. To determine an appropriate spread, you need to consider a series of questions: What is the average trading volume in the market? How much does this trading volume vary (variance)? What is the average size and variation (variance) of taker orders? What is the situation of limit orders near the fair price? And so on. Additionally, you need to consider price fluctuations and variance in very short time windows, as well as the fees that market makers have to pay/receive, and other secondary factors such as interface speed, order placement and cancellation speed, etc.

In very short time periods, the profit expectation for market makers is actually negative because every taker order wants to execute with you at a price advantage, unless it is a forced stop-loss order. Every other participant in the market wants to profit at your expense.

Imagine you are a market maker; where would you place your orders?

To maximize the spread while ensuring your orders can be executed, you need to place your orders at the front of the order book, at the buy/sell prices. As soon as the price changes, your buy order will be executed quickly, but frequent price changes are a bad thing— for example, if you just received goods and the price changes, your original sell order can no longer be executed at the order price.

In a market with insufficient liquidity and small price movements, placing orders at the buy/sell prices is much safer, but this raises another issue—other market makers will notice you and place orders with a smaller spread, tightening the spread. Everyone will compete to continuously narrow the spread until there is no profit left.

Now let's explore how to determine the spread from a mathematical perspective, starting with volatility. We need to know the volatility of the asset's price/volume around its mean over very short time periods. The following mathematical calculations will assume that price movements follow a normal distribution, which may deviate from actual conditions.

Assuming we take 1 second as the sampling period, with the past 60 seconds as the sample, let's assume the current mid price's mean is the same as the mean from 60 seconds ago (remember that this mean remains unchanged), and that this mean has a standard deviation of 0.04 from the current price. Since we previously assumed that price movements follow a normal distribution, we can further conclude that, 68% of the time, the price will fluctuate within 1 standard deviation ($-0.04 to +$0.04) from the mean; and 99.7% of the time, the price will fluctuate within 3 standard deviations ($-0.12 to +$0.12) from the mean.

Ok, we quote a spread of 0.04 on both sides of the mid price, meaning the spread equals 0.08. Since 68% of the time, the price will fluctuate within 1 standard deviation ($-0.04 to +$0.04) around the mean, for the orders on both sides to be executed, the price movement must breach the prices on both sides, meaning it must exceed 1 standard deviation. There is a 32% chance (1 - 68% = 32%) that the price movement will exceed this range. Therefore, we can roughly estimate the profit per unit time: 32% * $0.04 = $0.0128.

We can continue to deduce: If we place orders with a spread of 0.06 (at positions 0.03 away from the mid price), this corresponds to 0.75 standard deviations (0.03/0.04 = 0.75). The probability of the price movement exceeding 0.75 standard deviations is 45%, estimating the profit per unit time as 45% * 0.03 = $0.0135. If we place orders with a spread of 0.04 (at positions 0.02 away from the mid price), this corresponds to 0.5 standard deviations (0.02/0.04 = 0.5). The probability of the price movement exceeding 0.5 standard deviations is 61%, estimating the profit per unit time as 61% * 0.02 = $0.0122.

We find that placing orders with a spread of 0.06, which is at the position of 0.75 standard deviations, yields the maximum profit of $0.0135! This example illustrates the cases of 1/0.75/0.5 standard deviations, and comparing them, 0.75 standard deviations yields the highest profit. To further validate this intuition, I used Excel to derive expected returns under different standard deviations and found that the expected return is a convex function, which reaches its maximum value around 0.75 standard deviations!

The above assumes that price fluctuations follow a normal distribution with a mean of 0, meaning the market's average return rate is 0, while in reality, the mean price will change. A shift in the mean will make it harder for orders on one side to be executed, and when we have inventory, it not only leads to losses but also reduces the expected profit margin.

In summary, a market maker's expectation consists of two parts: first, the probability that the order will be executed, for example, placing an order at 1 standard deviation has a 32% chance of being executed; second, the probability that the order will not be executed, for example, placing an order at 1 standard deviation has a 68% chance that the price will move within the spread, resulting in the order not being executed.

When orders cannot be executed, the mean price is likely to change. Therefore, market makers need to manage "inventory costs," which can be viewed as a loan that incurs interest. Over time, this will lead to increased volatility, and the interest on the loan will also rise. Market makers can formulate regression strategies based on the average volatility over various periods to limit holding costs.

Finally, brothers, why do many retail investors say that every time they buy, the price drops, and every time they sell, the price rises? This is not unfounded; this article provides the answer!

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。