Written by: Agustin, Jae

Translated by: Glendon, Techub News

Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin today commented on the "pros and cons debate of prediction markets," stating: "An important point I want to add to the debate about the pros and cons of prediction markets is that most mainstream prediction markets currently do not pay interest, which makes them very unattractive for hedging. Because participating means giving up a guaranteed 4% annual return in dollars. I expect that once this issue is resolved, trading volume will further increase, leading to a large number of hedging application scenarios."

He also believes that ultimately, hedging will be the healthiest and most sustainable form of non-expert trading. There are many well-known correlations between prices and global events, so there are many ways to reduce statistical variance through reverse trading on Polymarket.

Previously, X user Jae (@TomJrSr) responded to and refuted KOL Agustin Lebron's article "Predicting Our Own Demise," emphasizing that "prediction markets are the early financial markets," which sparked intense discussion within the community.

The following are the original views of Agustin Lebron and Jae:

Prediction markets are thriving.

Polymarket's daily trading volume is about $30 million, and Kalshi's daily trading volume is similar, recently completing a new round of financing that values it at $2 billion. In terms of regulation, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) seem to have given up attempts to restrict Kalshi's transformation into a sports betting giant, rendering state-level sports betting regulations virtually meaningless. In fact, prediction markets are on the rise, and the overall situation in the gambling industry is similar. The world is heading towards decline.

At least theoretically, what reason is there not to love prediction markets? Economists like Robin Hanson have been advocating for prediction markets for decades. There is strong theoretical evidence that prediction markets can efficiently and accurately aggregate participants' information, just like financial markets. Who wouldn't want more accurate predictions about the future?

I want them. But prediction markets cannot truly deliver. And if these markets become large enough, they could destroy our society.

Prediction Markets Are Bad Markets

What constitutes a good market?

If we want to understand what makes a good market, let's look at the best existing markets: financial markets. The best and most efficient financial markets (such as S&P 500 futures or Treasury futures) share some common characteristics:

Standardized products: Every share of AAPL stock is the same as other stocks in the same category. This interchangeability allows the market to pool liquidity and improve efficiency.

Numerous participants: The market can only function optimally when the number of market participants is maximized. This way, whenever you want to trade, there is always someone willing to trade with you.

Low transaction costs: Compared to almost all other financial transactions, transaction costs in liquid financial markets are extremely low. Investors can buy $1 million of SPY ETF for less than $10 in fees.

Jae: "This is a product of efficiency and competition, but not a characteristic of a potentially efficient market."

Heterogeneous participants: When many different institutions are incentivized to contribute their knowledge and understanding, the market can find effective prices. High-frequency traders, arbitrage traders, long-term investors: everyone contributes their expertise, and all of this is essential for a well-functioning market.

Jae: "Prediction markets are still in a very early stage, but don't these currently efficient markets lack heterogeneous participants? Heterogeneity is a characteristic that gradually forms in efficient financial markets."

Lack of Hedgers

Fundamentally, financial markets can operate (and operate efficiently) because different participants have different risk preferences. This may come as a surprise, as we have always been taught that markets can only function well when people hold differing opinions about the value of trading products. While this indeed drives a lot of trading, relying solely on the "belief divergence" assumption can almost lead to a halt in trading. The problem lies in adverse selection.

Even if I possess private information about certain securities (say, that they are undervalued), I must cross the bid-ask spread to establish a position. And any party willing to trade with me knows that the only reason I am trading is that I have private information that the security is cheap. Therefore, they will gradually lower their quotes until trading with them becomes unprofitable for me. The result is no trading (or very little trading).

Jae: "This is true, but it only considers the direct outcomes for both parties, ignoring the key differences between traditional markets and prediction markets. First, traders with private information have no incentive to trade. Over time, as you mentioned, the market will be unable to maintain liquidity, and the only remaining participants will be those with private information. Second, in event-based markets, the amount of actionable private information people can have within a given timeframe and for a given event is limited. Theoretically, in prediction markets, due to less private information, the negative impact should be smaller than in traditional markets, leading to more effective long-term pricing and not significantly hindering others (hedgers) from becoming market participants."

But we do see a lot of trading; the S&P 500 futures (ES) have a daily trading volume close to $500 billion! The reason behind this is hedging. The trading volume of ES is so large because investors use it to hedge. They transfer unwanted risk and are very willing to pay (a small) fee for the service the market provides. It is this activity that generates all the trading we see in financial markets. People willingly engage in negative expected value (-EV) trading because these trades have positive utility for them. Even better, these trades also have positive utility for the counterparty because the risk preferences of both parties differ.

Jae: "Well said. This is undoubtedly an important reason why trading volume can continue to grow even in more efficient markets. That said, to establish an efficient market, other volume drivers, such as speculation, are also needed in addition to hedging. Where should you start, with hedgers or with speculators? Are there examples of markets that had significant trading volume early on? Hedging is a driver of trading volume, but its emergence is not a characteristic of a potentially efficient market. I do believe that the number of potential participants who can use the market for hedging can indicate whether a market can achieve efficiency levels similar to ES (S&P 500 futures)."

What is missing in prediction markets is precisely those hedgers, those participants with varying risk preferences, which has two structural reasons.

Jae: "I am sure that hedging trades have emerged, even if on a small scale. It would be foolish to assume that multiple participants have not given up some expected value (EV) in favor of utility or economic gain (EG). Look at the 2024 election and imagine the number of parties that could be affected economically, politically, and socially. The trading volume for the 2024 election (adjusted for time) is likely larger than the usual trading volume of many complex traditional financial markets. Should we believe that these traders are all speculators? If so, based on your previous argument, why is there such a large trading volume?"

B. Clearly, there are some binary events that can provide substantial economic value to the market; for decades, parties have been trying to trade in traditional markets through highly correlated but not completely correlated assets. You can provide cheaper and simpler hedging opportunities for interested parties through binary event contracts. I have listed many such examples below.

C. It is also worth asking how much of the hedging is driven by speculation. Of the total risk exposure that needs to be hedged, what proportion is a result of speculation? I guess that number is large. In prediction markets, this is not the case. Businesses, industries, and individuals are constantly (whether indirectly or forcibly) exposed to real-world events through their assets. Currently, they have no other cheap or simple way to hedge the risks of these events besides prediction markets. As the number of market participants grows, the value these markets provide to other markets will increase, and we will see the snowball effect that all successful financial markets have experienced."

Prediction Markets Are Binary Markets

The outcomes of prediction markets are either "yes" or "no." One type of information is referred to as "binary contracts." Binary contracts have been attempted many times before. In fact, these experiments have mostly failed. As far as I know, there are two reasons:

- They are almost impossible to hedge, so liquidity providers hate them. Liquidity providers try to minimize risk. For contracts with settlement prices as continuous numbers, you can almost always find a tool (usually the underlying security for derivative settlement) to hedge the risk. This makes providing liquidity relatively safe, so more people do it. But for binary contracts, assume the market trading volume is around 50%. If you short, and the settlement price is "yes," you will incur heavy losses, and vice versa. But you cannot reduce the risk; all you can do is pray. This means that the liquidity a trader can provide in a given contract is limited. All you can do is provide a small amount of liquidity across a large number of contracts and hope the law of large numbers works in your favor.

Jae: "Event contracts themselves are the underlying assets. They will be used to hedge the risk exposure of event contract derivatives, as well as the risk exposure of traditional securities and other derivatives. Furthermore, the idea that no one would be willing to help you reduce risk at a certain premium, even if the underlying asset itself is an event, is foolish. The premium may be relatively high, but is it enough to offset the liquidity incentives provided by hedgers? Ultimately, someone has to hold the underlying asset, but that does not mean it cannot be hedged."

- The second, more fundamental issue: it is hard to imagine what natural risks can be optimally hedged with binary contracts. Perhaps I am a politically appointed official facing the risk of a presidential election outcome. But even so, it seems (a) this is a small market; (b) given the presence of K Street (Washington lobbying groups, also known as Lobbying Street), the significance of economic risk is not obvious; (c) perhaps having a good social network can better hedge these risks. I believe that if you look closely, you will find that under closer scrutiny, most or all of the so-called hedging value of binary contracts will disappear.

Jae: "A. Of course, perhaps for you as a politically appointed official, this market is too small, but for someone who may have to pay a few hundred dollars more in taxes due to a new president being elected, is the market really that small? All markets have a starting point, and judging its future economic value solely based on market size is clearly wrong.

B. Do you really think K Street can completely mitigate your risk of political failure? Moreover, it will have a greater impact on your economy, and that impact will far exceed your political career.

C. Perhaps you are right in this specific case, but just because it is better does not mean that other methods are worthless."

It is worth noting that we already have a term to describe continuously valued prediction markets: cash-settled futures.

Jae: "These markets are based on the prices of underlying assets, but they are less attractive and applicable to potential hedgers (whose risk exposure does not stem from speculation). But why wouldn't hedgers choose actual events they believe will affect their positions as much as possible?"

Selfishness Above All

The lack of natural hedgers in prediction markets ultimately becomes their fatal weakness. Everyone in the market is either a noise trader (a euphemism for "degenerate gambler") or a savvy trader. The former will eventually run out of funds, leading to mature prediction markets filled with individuals who share the same risk preferences and goals: making money through trading. This brings us back to the "no-trade theorem."

Jae: "I can't imagine how many entities have accumulated risk exposure to ES through non-speculative means. There are even more potential examples where parties have accumulated risk exposure to binary event contracts through non-speculative means; I have listed some examples below."

The only way for prediction markets to sustain themselves is to rely on a continuous influx of new gamblers willing to lose money to savvy traders. It's no wonder platforms like Kalshi and Polymarket are so supportive of regulatory relaxation. After all, all the real money is locked up in institutions: pension funds, mutual funds, and so on. If prediction markets can provide value to institutional participants, why cling to bringing retail investors onto their platforms? The answer is obvious. Prediction markets can only function if they consistently receive a supply of "dumb money."

Jae: "This situation won't last forever; the market will continue to grow, and as these markets grow, more participants will be incentivized to trade."

Self-Referentiality of Markets

I can hear you saying, "Well, that's just your opinion. What if you're wrong?"

Maybe I am wrong. Perhaps prediction markets will naturally give rise to a type of hedger I haven't thought of. But even so, prediction markets are still bad, and this could be fatal for the social structure we currently enjoy. The reason lies in self-referentiality. (Techub News note: The self-referentiality of markets, also known as reflexivity, refers to the way market participants' perceptions and expectations directly influence market trends, and the feedback from market trends reinforces or alters participants' perceptions, creating a two-way interactive feedback loop.)

Jae: "What comes to mind—

Agricultural producers: rainfall, drought, temperature, frost dates

Utility companies: average monthly temperature

Theme parks: seasonal weather impacts on visitor numbers

Airlines: hurricane frequency, snowstorms

Hotels: natural disasters, tourist numbers

Cruise companies: travel warning levels, outbreak events, tropical storms

Retail chains: consumer confidence index, travel rates

Real estate developers: interest rate announcements, home sales data

Logistics companies: global shipping rates, port strike outcomes, export/import data

Pharmaceutical companies: FDA approval/rejection events, regulatory change events

Insurance companies: natural disasters, death tolls, vaccination rates

Energy companies: OPEC production quotas, sanction outcomes

Defense contractors: defense budget approvals, conflict outcomes, political outcomes

Imagine trying to hedge the risks posed by any of the above events in a simple, low-cost way. In today's market, you can hardly do that. There are almost countless participants needing to hedge event outcomes, but currently, they lack the means to do so."

A "Clean" Prediction Market

Take solar radiation as an example; suppose there is a prediction market. Solar activity varies over time, with periods of high sunspot activity corresponding to higher radiation levels. Sometimes, the sun may remain inactive for extended periods, affecting the climate accordingly.

Therefore, trading in a prediction market about whether the number of sunspots will exceed a threshold might be reasonable. This could help farmers hedge against crop prices when reduced solar activity leads to unfavorable weather. So far, so good. The reason I chose such an apparently extreme example is that, as far as I know, we cannot influence solar activity. The sun will operate according to its own rules regardless, especially not changing due to our prediction market forecasts. The sunspot prediction market has no causal relationship with the number of sunspots.

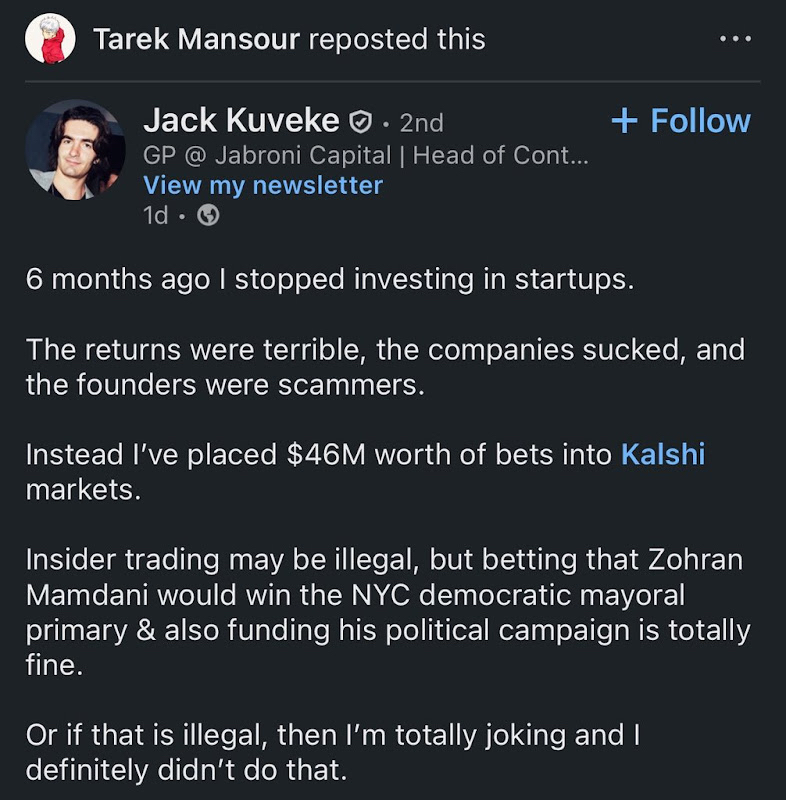

"The Tail Wagging the Dog"

Now, take a look at this tweet.

The main selling point of prediction markets (aside from the argument of "easy gambling") is that they are a way to aggregate information and create a mechanism for seeking truth through simple self-interested behavior. But this perspective completely ignores reflexivity. If the existence of prediction markets directly influences event outcomes, then it is no longer a quest for truth.

Once prediction markets become large enough, they shift from seeking truth to seeking the realization of predictions.

Again, it is emphasized that the existence of prediction markets itself influences and distorts the underlying events being predicted!

Jae: "An illustrative example is as follows:

Suppose there is a market: 'Will candidate X drop out of the election before September?'

As a large trader, if you heavily short 'no,' this signal may influence media coverage or donor confidence, thereby increasing or decreasing the actual likelihood of candidate X dropping out.

Now, your trade not only conveys information—it also changes the world.

This leads to adverse selection:

If your trade results are unfavorable to you, then you effectively become 'dumb money,' spending to skew the truth. If your trade results are favorable, the price will depreciate, detaching from reality, and the market will lose substantial economic value.

Rational market participants will recognize this and avoid participating in markets that may alter objective facts."

This is Not the First Instance

This is not a new phenomenon. In financial markets, whenever the scale of the derivatives market (in terms of liquidity, trading volume, etc.) exceeds that of the underlying assets determining their value, this situation arises. Especially in cash-settled derivatives, the definition of prediction markets lies here. For example, the recent actions taken by India's Securities and Exchange Board (SEBI) against Jane Street, which was accused of manipulating the underlying stock market to increase the profits of its options positions.

The same thing can happen not only in prediction markets but is also positively incentivized.

Atmosphere Economy

Twitter user @goodalexander has written extensively about what he calls the "attention economy" or (I prefer to use this term) "atmosphere economy."

Define "nonsense" as whether something is true is irrelevant.

Define "atmosphere economy" as the ability to capture the public with nonsense, possessing core economic value.

For example, whether what Joe Rogan says is true is irrelevant. The more he says it, the more it "becomes a fact," and the more people believe it to be true and act accordingly. Clearly, the "current resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue" is well aware of this dynamic.

Back to prediction markets. Prediction markets are a way to decentralize the atmosphere/nonsense generation process, allowing participants to directly reap the economic benefits of these atmospheres. Now remember reflexivity. By creating economic incentives to manipulate probabilities, as long as the atmosphere is somewhat manipulable, it can actually become reality.

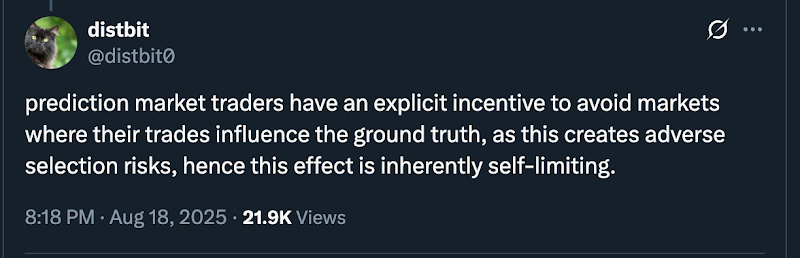

Jae: "These markets will also naturally fade away due to reflexivity."

Specific Cases

Now, let’s consider a prediction market about "Will Trump run for re-election in 2028?" If the market is small, then it is a true prediction market. It will not affect the final outcome.

Now imagine a prediction market with billions of dollars in daily trading around this question. People are discussing it, thinking about it, and looking for ways to realize it. Now this has become an atmosphere. A significant amount of social resources are mobilized to support or oppose it. This feedback loop directly increases the probability of those rare and volatile events occurring through the mobilization of resources.

Similarly, the probability of highly likely events occurring will be reduced.

Jae: "Shouldn't these forces balance and offset each other in the market? Why would traders with lower realization probabilities naturally be more motivated than their counterparts to influence the outcome?"

Now ask yourself, is this process beneficial to society? I think it is clearly not beneficial. Because society itself is fragile and vulnerable.

Destruction is much easier than construction. Jae: "It feels more like a worldview rather than having any particular relation to prediction markets."

The "significance" or atmosphere of negative events naturally attracts more audiences. Jae: "This is true, but equally true is that 'bad' events usually have the most direct economic impact on potential affected parties. Think of civil wars versus artificial general intelligence (AGI). Civil wars can lead to immediate industry collapse, while AGI may take decades to fully integrate into society. This brings us back to your original point. Destroying something is easier than building it."

The profit margin for betting on rare events occurring is much larger.

Thus, prediction markets will naturally focus more on questions like "Will there be a civil war in 2030?" rather than "Will we discover anti-gravity in 2030?" Jae: "I agree with this, but for the reasons mentioned earlier, these markets will provide more direct economic value to potential hedgers."

So, atmosphere markets (and prediction markets) will be dominated by trivial and resource-consuming content (like sports) or results with negative social impacts.

Jae: "Sports events can also attract those hedgers who previously could not manage risk. Think of the Brooklyn Nets trying to hedge against the risk of the Knicks winning the championship, or think of venues trying to hedge against ticket losses due to poor team performance; there are countless similar cases."

But aren't financial markets the same?

Not at all.

The self-referentiality of financial markets (typically) generates positive externalities rather than negative externalities. Those investing in Tesla or Nvidia create venture capital that funds competitors. New ideas receive funding, technological advancements occur, and we all become wealthier, making the markets more efficient.

The meme stock phenomenon could be considered an exception. The more financial markets are invaded by the atmosphere economy, the more detrimental it is to these markets and the world as a whole. However, let's save that discussion for later.

Conclusion

Prediction markets are poorly designed and induce bad incentives.

But there is still time to put the "devil" back in the box.

So let’s take action.

Jae: "Prediction markets provide hedging opportunities for many entities that were previously overlooked, rewarding those with the correct views of the future and incentivizing the truth (rather than a fantasy of the truth) to spread in society."

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。