# I. Introduction

On November 25, 2024, the Shanghai Malu Grape Asset On-Chain Project made a high-profile debut as the "first case of RWA (Real World Asset Tokenization) in Chinese agriculture." The project claims to achieve "data assetization of vineyards" through blockchain technology and simultaneously completed 10 million yuan in equity financing and 200,000 yuan in NFT financing at the Shanghai Data Exchange. The official narrative positions it as a benchmark for "technology empowering real agriculture," sparking widespread discussion in the industry about the localization path of RWA.

However, peeling back the surface glamour, the essence of this project is far from a true RWA innovation. The so-called "tokenization" is essentially a traditional financing reconstruction with NFT digital collectibles as a compliant shell and SPV equity structure as the core—where the rights to income tokens are castrated, governance rights remain with centralized entities, and consumer NFTs merely serve as pre-sale cards. This "de-financialization" survival strategy, born under regulatory pressure, breaks through in the name of technology but falls into a deep dilemma of rights fragmentation, liquidity suppression, and lack of empowerment for producers.

This article will use the Malu Grape Project as a case study to reveal three fundamental contradictions behind its "RWA benchmark" illusion:

The dilemma of technological instrumentalization: Blockchain has become a tool for enhancing credibility, failing to touch upon the transformation of agricultural production relations;

The logic of regulatory arbitrage: Avoiding policy red lines through SPV equity isolation and NFT non-securitization definitions;

The cost of localization compromise: The complete separation of data income rights from producers (farmers), deviating from the original intention of RWA inclusiveness.

By deconstructing the entire process from asset selection, on-chain mapping to financing design, this article will argue that the core proposition of digitalizing agricultural assets in China is not about technological replication, but rather how to balance compliant survival with real value creation under policy constraints. The paradoxical practice of Malu Grape provides a key mirror for exploring the limitations and possibilities of local RWA.

# II. Process Breakdown

1. Asset Selection and Compliance Confirmation

RWA refers to the tokenization of physical or financial assets from the real world through blockchain technology, enabling them to circulate, trade, and be managed in a decentralized network.

This requires the project team to screen target assets before the project begins, ensuring that the asset attributes are suitable for tokenization and that there are no compliance issues in the real world:

Must be real and valuable assets

Must have stable cash flow or appreciation potential

Must have clear ownership, with no disputes

"Malu Grape" is a geographical indication agricultural product from Shanghai, with over 40 years of cultivation history, loved by consumers for its excellent quality and unique taste.

Data shows that in 2023, the area of concentrated planting of Malu grapes reached 4,051.96 acres, with a total output of 4,437.83 tons and a total output value of 107 million yuan, averaging 27,320 yuan per acre and an average price of 24 yuan/kg. The planting area and economic benefits of Malu grapes occupy an important position in Shanghai's grape industry, accounting for 12.9% of the city's grape planting area and 17.17% of the total economic benefits.

Currently, Malu Town has formed an industrial joint development model of "research institute + enterprise + cooperative + farmers." The research institute is responsible for the research and promotion of new varieties and technologies, enterprises handle brand building and marketing, cooperatives organize farmers for standardized production, and farmers plant and manage according to requirements.

In terms of product quality, Malu grapes include over 50 varieties such as Black, Xile, Jingmi, Jufeng, Juemei, Zui Jinxiang, Sunshine Rose, and Nina Queen, and have established a sound management system for field records, testing and inspection, packaging labeling, quality traceability, and trademark usage, combined with a digital cloud platform to achieve "one string, one code" traceability management, making it a benchmark for digital agricultural production and meeting the asset conditions for RWA tokenization.

2. Technical Packaging and On-Chain Mapping

One of the keys to RWA projects is to ensure the authenticity of off-chain data once it is on-chain, which is a decisive factor for the success of RWA projects.

(1) Data Collection

During the cultivation of Malu grapes, a tight data collection network is built using IoT devices.

In terms of environmental data, real-time collection of environmental parameters such as temperature, humidity, light intensity, and soil pH during the grape cultivation process, as well as recording agricultural activities (such as irrigation and fertilization) data.

In terms of economic data, sales data (such as sales volume, price), logistics information (transportation duration, loss rate), and brand value (such as geographical indication certification, certification information, consumer reputation, etc.) are included in the asset package.

(2) Asset Packaging

Integrating data from over 300 sensors across 600 acres of vineyards (soil pH, temperature, humidity, growth cycle, etc.), a "Data Asset Shell (DAS)" is constructed. DAS is an innovative "data asset shell" service system launched by the Shanghai Data Exchange, responsible for compliance certification of data and standardized processing. Different types and sources of data are uniformly organized to enable orderly integration on-chain, forming "true data" recognized by multiple parties on-chain (including growers, operators, regulatory agencies, investors, etc.), laying a solid foundation for subsequent asset valuation and trading.

Once data packaging is completed, it is stored on-chain through the SwiftLink platform, achieving trustworthiness throughout the agricultural production process. Traceability leverages blockchain technologies such as the SwiftLink management platform to instantly put the collected massive data on-chain. The immutability of blockchain ensures that once data is entered, it cannot be maliciously modified, safeguarding data authenticity and integrity.

On the other hand, using AMC (multi-chain synchronization) technology, data is simultaneously stored on the Shanghai "Pudong Data Chain," achieving on-chain credibility enhancement.

(3) Asset Valuation

A comprehensive valuation of the integrated Malu grape data assets is conducted using various scientific methods.

The cost-plus method accounts for a series of direct input costs from data collection equipment investment, labor costs to data processing operations; the market premium method assesses the additional value conferred by the Malu grape geographical indication brand based on its market premium performance; the income discount method forecasts future income increases from data applications, such as cost reductions from precision irrigation and brand value enhancement from traceability systems reducing counterfeits.

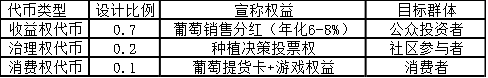

(4) Token Model Design

Based on the valuation results, the assets are converted into tradable digital tokens.

The project designed a layered token economic model, with income rights tokens accounting for 70%, closely tied to grape sales revenue, providing investors with an annualized benchmark dividend of about 6%, attracting stable investors such as bank wealth management funds;

Governance tokens account for 20%, allowing holders to vote on major decisions regarding the vineyard (such as introducing new varieties and expanding sales channels), attracting deep participation from industrial investors;

Consumer rights tokens account for 10%, linked to product discount rights, such as holding this token to enjoy an 80% purchase right for Malu grapes, enhancing C-end user stickiness while recouping some sales funds in advance.

3. SPV Structure and Financing Design

In October 2023, Shanghai Left Bank Xinhui Electronic Technology Co., Ltd. and Shanghai Left Bank Investment Management Co., Ltd. jointly invested 10 million yuan to establish Left Bank Xinhui (Shanghai) Data Technology Co., Ltd. as the project's dedicated SPV.

The SPV independently carries the Malu grape data asset package (including agricultural production data and brand rights), completely isolating it from the parent company's other businesses to avoid risk transmission.

The SPV company's 100% equity is held in custody at the Shanghai Equity Custody Registration Center and is stored on the blockchain platform "Guyu Chain," achieving transparency of ownership.

At this point, a significant and interesting change occurs in the project.

Since Malu grapes operate in mainland China and circulate on the Shanghai Data Exchange, according to the "Announcement on Preventing Risks of Token Issuance Financing" (2017) and the "Initiative to Prevent Financial Risks of NFTs," the issuance of securitized tokens is prohibited in mainland China. Ultimately, Malu grapes did not proceed with financing and circulation according to the initial token model but chose to sacrifice liquidity and adopt a "de-financialized" RWA route.

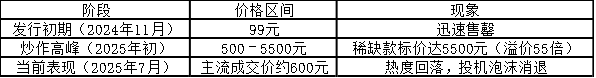

In practice, consumer rights tokens are not presented in token form but appear as NFT digital collectibles, clearly defined as "digital souvenirs," avoiding the red line of the "Announcement on Preventing Risks of Token Issuance Financing." Ultimately, 2024 NFTs were issued (including 1,924 basic versions and 100 scarce versions), with 2,013 publicly sold (accounting for 99.3%), and the project team retained 11 (for brand cooperation or airdrops), with an initial price of 99 yuan each. Thus, the Malu Grape project NFT completed 200,000 yuan in financing.

Next, governance rights belong to the project team, and income rights belong to investors, integrating income rights and governance rights into the SPV equity structure, open only to institutions, allowing Malu grapes to secure 10 million yuan in financing from investors. The 10 million yuan financing is based on SPV equity trading, where investors indirectly control the income rights of data assets through shareholding, complying with the regulatory framework of the "Securities Law" for equity trading.

4. Liquidity Management

(1) Issuance Situation

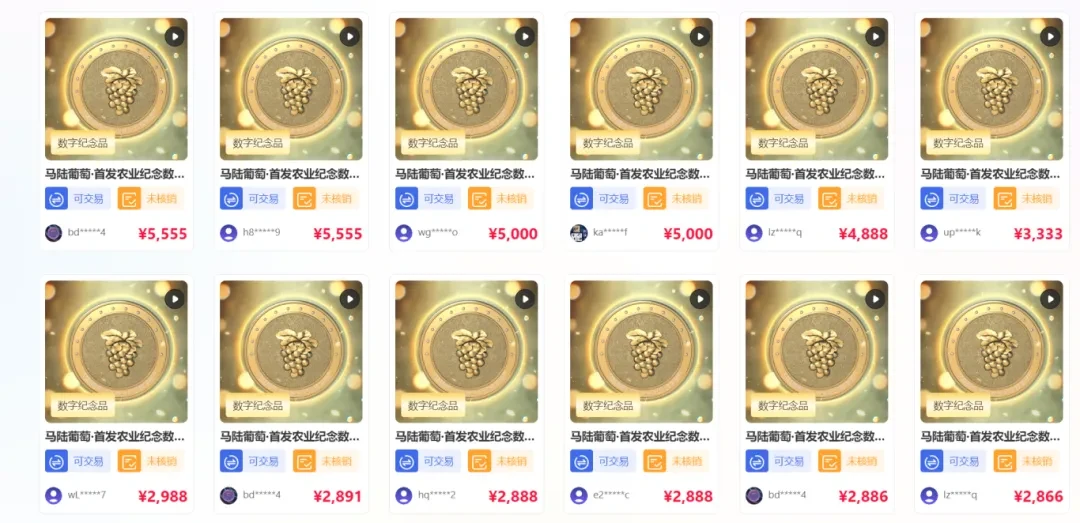

On November 25, 2024, Malu Grape NFT digital collectibles were publicly issued on the Shanghai Data Exchange, quickly selling out after issuance, with trading currently only available in the secondary market.

Each NFT includes two layers of basic and ancillary rights:

Basic Rights: Includes 1,924 basic NFTs and 100 scarce NFTs. The basic version comes with a 2-pound pickup card for "Sunshine Rose" grapes, valued at about 200 yuan, valid until December 8, 2025; the scarce version includes a 2-pound pickup card for "Nina Queen" grapes + 2 tickets to Malu Park, valued at about 300 yuan, with the same validity as the basic version.

Ancillary Rights: Can access the "Malu Planet" interactive platform, participate in virtual grape planting games, and redeem points. The top 50 users by trading volume before December 31, 2024, will receive an additional "early-maturing variety" pickup card.

(2) Circulation Mechanism

Trading Restrictions: Trading is limited to December 9, 2024, to December 8, 2025, with mandatory delisting upon expiration; a single user’s holding cannot exceed 5% of the total issuance (approximately 101 units), and exceeding this limit requires splitting and selling; after a single sale, a waiting period of 5 trading days is required before trading can occur again.

Redemption and Exit: After activating the pickup card, the NFT is redeemed on-chain, retaining only the qualification for platform interaction; if the vineyard is damaged (e.g., by fire), the project team has not publicly disclosed a compensation plan, creating a gap in rights protection.

(3) Market Performance

# III. Power Map

The tokenization of real assets is a capital operation that requires the participation and collaboration of multiple parties. Below, we will outline the various participants in the Malu Grape Project and their main responsibilities from the perspective of the participants, re-examining the project value of Malu Grape from a holistic perspective.

We can categorize the participants into two types: core participants and supporting institutions.

1. Core Participants

Left Bank Xinhui (Project Operator): Responsible for integrating grape production data and brand qualifications, issuing NFT digital assets, and managing equity financing funds, making it the core participant of the entire project.

Shanghai Data Exchange (Compliance Trading Platform): Responsible for providing "Data Asset Shell (DAS)" on-chain storage services, building NFT trading channels, and ensuring compliance with information disclosure.

Malu Town Economic Development Service Center (Government Coordination Party): Responsible for policy endorsement and resource connection.

"Malu Grape" Planting Enterprises (Underlying Asset Providers): Provide physical grape assets and generate agricultural data.

2. Supporting Institutions

Technical Infrastructure Service Providers: Provide underlying blockchain technology support to achieve on-chain data storage.

Compliance and Risk Control Institutions: Design compliance frameworks and audit the authenticity of real assets.

Asset Valuation Institutions: Asset pricing.

Equity Custody Institutions: Custody of SPV company equity to ensure transparency in equity trading.

Through the above analysis of the functions of each participant, we can see that the structure of participants in the Malu Grape RWA project is essentially a market-oriented co-governance experiment guided by the government. Through the triple nesting of "State-owned Asset Chain (Pudong Data Chain) + SPV + Parent-Child Brand," it ensures compliance (avoiding securitization risks) while activating industrial chain efficiency (with an average output value per acre reaching 1.7 times the Shanghai average). It is a complex economic activity that requires multi-party coordination and fully mobilizes production factors.

# IV. Source of the Problem: How the Three Characteristics of Pseudo-RWA Anchor the Localization Dilemma

Thus, through the dissection of the Malu Grape Project, we can identify a fact. Contrary to some promotional claims, Malu Grape does not belong to a true RWA project for the following reasons:

A typical RWA project represents corresponding income shares after asset tokenization, which can circulate freely on a global scale and automatically distribute dividends through smart contracts.

As defined by RWA—Real World Asset refers to the tokenization of physical or financial assets from the real world through blockchain technology, enabling them to circulate, trade, and be managed in a decentralized network.

In contrast, the Malu Grape project strictly defines the 2024 NFTs as digital collectibles, binding only to consumer rights, anchoring the ownership of future grapes, without involving potential future income. At the same time, strict limitations on circulation essentially classify it as a pre-sale of agricultural products.

From the perspective of income rights ownership, NFT holders only receive grape pickup cards (valued at 200-300 yuan) and game points, with no share in the data asset income. This income entirely belongs to SPV shareholders, completely severing the connection between data income and users. The project team claims "token binding income dividends," but in reality, the SPV equity structure completely isolates income rights from NFT holders.

Regarding governance rights, whether it is the introduction of new varieties or technological upgrades, it is still controlled by the SPV company, local government (Malu Town Economic Development Service Center), and technology providers (Ant Chain), with no public voting opened. "On-chain governance" serves as an internal decision-making tool for the SPV, contrary to the DAO concept.

In summary, the essence of the Shanghai Malu Grape RWA is a capital operation where NFTs serve as a compliant shell, and equity financing carries the core value. It is a "chain shell + traditional financial core," where technology serves only to enhance credibility rather than liberalization, representing a "Chinese-style" RWA project with high government involvement.

On one hand, we should recognize the correct positioning of this project (essentially equity financing); on the other hand, we should also see the duality of this project, which is a compromise under compliance pressure while also opening up technological innovation in the cracks, providing pioneering reference significance for exploring RWA projects in the current agricultural field in mainland China.

# V. Breaking the Wall Experiment: A Ladder Path from Real Compromise to Ideal Reconstruction

The duality of the Malu project—compromising with technology for survival under regulatory constraints while sacrificing the core value of RWA—reflects the deep-seated dilemma of digitalizing agricultural assets in China: when "compliance survival" squeezes "real innovation," where is the breakthrough path? If we replicate its SPV isolation technique and NFT de-financialization path, we will fall into a cycle of "policy privilege dependence" and "lack of producer empowerment"; if we return to the true RWA path, we must face threefold constraints: policy repression, technical cost, and non-standard rights distribution. The following breakthrough experiments may provide a gap to tear the iron curtain.

1. Analysis of Project Promotion Difficulty

The core value of the Malu Grape Project lies in pioneering the localization path of agricultural RWA, but its promotion faces three structural obstacles:

(1) Non-replicability of Policy Dependence

The project heavily relies on the Shanghai Pudong Data Chain (a state-owned asset alliance chain) and government coordination mechanisms, while most agricultural areas nationwide lack such infrastructure support. For example, non-pilot areas find it difficult to obtain compliance endorsement from data exchanges, and the mainland's prohibition of homogeneous token trading creates a policy red line, forcing other agricultural enterprises to only imitate its "consumer-type NFT" compromise solution, unable to achieve true income rights openness.

(2) Scale Threshold of Technical Costs

Deploying over 300 IoT sensors across 600 acres of core area incurs an average equipment investment of over 20,000 yuan per acre, far exceeding the capacity of small and medium-sized farmers. Ordinary agricultural products (e.g., cabbage) have a premium rate of less than 5%, which cannot cover costs, while Malu grapes rely on a 20% brand premium from geographical indications to achieve breakeven. If promoted to low-value-added categories, a regionally co-built IoT platform (e.g., county agricultural cloud) is needed, but cross-entity data integration faces ownership disputes.

(3) Industry Limitations of Asset Standardization

Grapes are easy to standardize due to "one string, one code" traceability and controlled cultivation, but categories like tea and aquatic products lack unified data collection standards. For instance, the quality of tea is influenced by subjective factors such as microclimate and picking methods, making it difficult to generate credible data packages on-chain, leading to a lack of consensus on asset valuation.

(4) Essential Contradiction

The Malu model is essentially a special case of "strong policy area + high premium products," and its technological dividends are only applicable to scarce agricultural products like Wuchang rice and Yangcheng Lake hairy crabs. Replicating in ordinary agricultural areas requires breaking through cost constraints and data property distribution dilemmas—EU regulations stipulate that original data producers (farmers) should enjoy 40% of income rights, while in the Malu project, 27 cooperatives only serve as data providers and do not participate in SPV dividends.

2. Conditions for Achieving Complete RWA Form

(1) Compliance of Asset Securitization as a Precondition

Avoiding regulatory pitfalls in the mainland, choose jurisdictions like Hong Kong/Singapore that recognize income rights tokens. Underlying assets must have stable cash flow (e.g., annual revenue from charging piles > 30 million yuan), approved through the CSRC's No. 1 license, and disclose asset audit reports. The Malu project, due to grape revenue being affected by climate fluctuations, was forced to replace hard cash flow with "data appreciation potential," weakening the credibility of asset anchoring.

(2) Design of Technical Penetration

Use oracles (e.g., Chainlink) to verify off-chain asset status in real-time, ensuring a strong correlation between token value and physical assets. In contrast, Malu only stores environmental data on the Pudong Data Chain, failing to achieve automatic on-chain income, and NFT holders cannot receive dividends through smart contracts. True RWA requires deploying ERC-3643 standard contracts (including dividend modules) to support daily income automatically distributed to wallets.

(3) Dual Construction of Liquidity

The primary market should privately place offerings to qualified investors through licensed exchanges (e.g., Hong Kong HashKey); the secondary market should connect to DEXs like Uniswap, with market makers ensuring trading depth. In contrast, Malu NFTs are limited to trading on the Shanghai Data Exchange platform, with an average daily transaction volume of less than 10, and mandatory delisting in 2025 artificially suppresses liquidity.

(4) Key Leap

True RWA must complete the cross-border separation of "domestic assets + overseas financial ends." The QFLP channel in Hainan Free Trade Port can serve as a springboard—domestic state-owned asset chains store asset ownership, while overseas SPVs issue income tokens, balancing compliance and capital freedom.

3. Future Outlook for Agricultural RWA 4.0

Currently, the Malu project is stagnant at Stage B (assets can be split but not circulated) and needs the Hong Kong/Hainan sandbox to achieve the leap from C to D. The development of agricultural RWA requires phased breakthroughs in institutional and technical bottlenecks, with the ultimate goal of returning sovereignty to producers.

(1) Short-term: Mixed Rights Experiment in the Sandbox

Implement a "consumer-type NFT + micro-income rights" mixed model in pilot areas like Hainan and Hengqin, with an annualized income cap set at 3% to comply with consumer rebate regulatory standards. For example, the Hainan durian project plans to return 1.5% of harvesting income to NFT holders through smart contracts, avoiding securitization recognition while enhancing user stickiness. At the same time, establish an "agricultural data bank" to support pledge loans for planting data from tea gardens, rice fields, etc., replicating the Malu project's 1.5 million yuan bank credit model.

(2) Mid-term: Breakthrough in Data Property Legislation

Promote the introduction of the "Regulations on the Registration and Management of Agricultural Data Assets," clarifying the three-party rights allocation ratio: farmers receive 40% of the original data income (as providers of production materials), cooperatives receive 30% (as data integrators), and the technology platform/government receives 30% (for infrastructure investment and regulatory costs). By solidifying the rights division rules through on-chain storage, address the pain point of "lack of governance rights" for small farmers in the Malu project.

(3) Long-term: Producer Sovereignty under DAO Governance

Construct an on-chain cooperative model: Farmers gain voting weight based on their land data contribution, while consumers participate in variety introduction decisions through governance tokens. For example, when the IoT detects a 15% improvement in drought resistance for a certain grape variety, a DAO vote decides to expand the planting area, and a smart contract automatically adjusts the production plan and allocates income. This structure allows code to become the "hoe" of the new era, reconstructing the subjectivity of small farmers in the digital economy.

(4) Core of the Chinese Paradigm

The ultimate value of agricultural RWA lies in "technology being globally applicable while production relations are locally reconstructed." In the short term, accept the transitional nature of consumer-type NFTs, and in the long term, empower farmers with data pricing rights through on-chain cooperatives (DAOs), allowing producers in the fields to truly become the primary distributors of digital dividends.

# VI. Conclusion

The essence of the Malu Grape Project is a revolution bound by shackles—when the distributed ideals of blockchain encounter the iron wall of real-world regulation, it chooses to retreat to advance: using the "compliance shell" of consumer-type NFTs to cover the real breakthrough of IoT and traceability technology, leveraging a small leverage of 200,000 digital pickup vouchers to pry open 10 million in equity financing for industrial upgrades. This dialectic of compromise and innovation is akin to a seed growing in the cracks of a rock: bending down is not for submission, but to gather strength to break through the soil.

The true legacy of the Malu Grape Project is that it provides a dialectical model for the digitalization of agriculture in China:

It proves that under high-pressure regulation, consumer-type NFTs are the only safe entry point, while the opening of income rights needs to rely on offshore hubs (such as the Hainan QFLP channel);

It reveals that IoT + blockchain can achieve "asset disassembly," but "capital accessibility" relies on breakthroughs in cross-border liquidity;

It indicates that the endpoint of RWA should be the awakening of producer sovereignty—when farmers grasp data pricing rights through DAOs, technological innovation truly elevates to become the engine of rural revitalization;

The core proposition of agricultural modernization has never been about the replication of technology, but rather the reconstruction of production relations. All "atypical RWAs" are shadows cast by the times. The compromise and breakthrough of Malu Grape are like a seed deeply buried in the soil—it may not reach the sky, but in its curved posture, it marks the direction for future generations to break through the ground.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。