Original text from Rick Maeda

Translation|Odaily Planet Daily Golem (@web3golem)_

One fact is that most crypto users are not hacked through complex vulnerabilities, but rather through clicking, signing, or trusting the wrong things. This report will analyze in detail these everyday security attacks that occur around users.

From phishing toolkits and wallet theft tools to malware and fake customer service scams, most attacks in the crypto industry are directly aimed at users rather than protocols, which means that common attacks focus on human factors rather than code. Therefore, this report outlines vulnerabilities in cryptocurrency targeting individual users, covering not only a range of common vulnerabilities but also practical case analyses and precautions that users need to be aware of in their daily lives.

Note: You are the target of the attack

Cryptocurrency is designed to be self-custodial. However, this fundamental attribute and core industry value often make you (the user) a single point of failure. In many cases of personal cryptocurrency fund loss, the issue is not a protocol vulnerability, but rather a click, a private message, or a signature. A seemingly trivial daily task, a moment of trust or negligence, can change a person's cryptocurrency experience.

Therefore, this report does not focus on smart contract logic issues, but rather on personal threat models, analyzing how users are exploited in practice and how to respond. The report will focus on individual-level vulnerability attacks: phishing, wallet authorization, social engineering, and malware. The report will also briefly introduce protocol-level risks to outline the various vulnerabilities that may occur in the cryptocurrency field.

Analysis of Vulnerability Attack Methods Faced by Individuals

Transactions occurring in an unpermissioned environment are permanent and irreversible, typically without the involvement of intermediaries. Additionally, individual users need to interact with anonymous trading counterparts on devices and browsers holding financial assets, making cryptocurrency a hunting ground for hackers and other criminals.

Here are various types of vulnerability attacks that individuals may face, but readers should note that while this section covers most types of vulnerability attacks, it is not exhaustive. For those unfamiliar with cryptocurrency, this list of vulnerability attacks may be overwhelming, but a significant portion of these are "conventional" vulnerability attacks that have occurred in the internet age and are not unique to the cryptocurrency industry.

Social Engineering Attacks

Attacks that rely on psychological manipulation to deceive users, putting their personal safety at risk.

Phishing: Fake emails, messages, or websites that mimic real platforms to steal credentials or mnemonic phrases.

Impersonation Scams: Attackers impersonate KOLs, project leaders, or customer service personnel to gain trust and steal funds or sensitive information.

Mnemonic Phrase Scams: Users are tricked into revealing recovery mnemonic phrases through fake recovery tools or giveaways.

Fake Airdrops: Users are lured with free tokens, leading to unsafe wallet interactions or private key sharing.

Fake Job Opportunities: Disguised as employment opportunities but aimed at installing malware or stealing sensitive data.

Pump and Dump Scams: Using social media hype to sell tokens to unsuspecting retail investors.

Telecom and Account Takeover

Exploiting telecom infrastructure or account-level vulnerabilities to bypass authentication.

SIM Card Swapping: Attackers hijack the victim's phone number to intercept two-factor authentication (2FA) codes and reset account credentials.

Credential Stuffing: Reusing leaked credentials to access wallet or exchange accounts.

Bypassing Two-Factor Authentication: Exploiting weak authentication or SMS-based verification to gain unauthorized access.

Session Hijacking: Stealing browser sessions through malware or insecure networks, thereby taking over logged-in accounts.

Hackers once used SIM card swapping to take control of the SEC's Twitter and post false tweets.

Malware and Device Vulnerabilities

Infiltrating user devices to gain wallet access or manipulate transactions.

Keyloggers: Recording keystrokes to steal passwords, PINs, and mnemonic phrases.

Clipboard Hijackers: Replacing copied wallet addresses with addresses controlled by attackers.

Remote Access Trojans (RAT): Allowing attackers to gain full control of the victim's device, including the wallet.

Malicious Browser Extensions: Compromised or fake extensions that steal data or manipulate transactions.

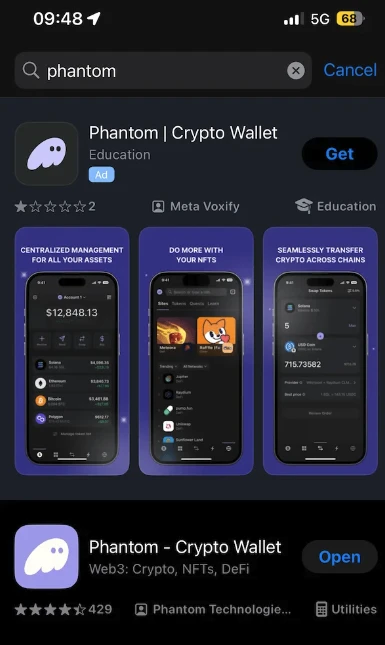

Fake Wallets or Applications: Counterfeit applications (Apps or browsers) that steal funds when used.

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) Attacks: Intercepting and modifying communications between users and service providers, especially on insecure networks.

Insecure WiFi Attacks: Public or infected WiFi can intercept sensitive data during login or transmission.

Fake wallets are a common scam targeting cryptocurrency newcomers.

Wallet-Level Vulnerabilities

Attacks targeting how users manage or interact with wallets and signatures.

Malicious Authorization Depletion: Malicious smart contracts exploit previous token authorizations to deplete tokens.

Blind Signature Attacks: Users sign vague transaction conditions, leading to fund loss (e.g., from hardware wallets).

Mnemonic Phrase Theft: Leaking mnemonic phrases through malware, phishing, or poor storage habits.

Private Key Leakage: Insecure storage (e.g., in cloud drives or plaintext notes) leading to key leakage.

Hardware Wallet Leakage: Tampered or counterfeit devices leaking private keys to attackers.

Smart Contract and Protocol-Level Risks

Risks arising from interactions with malicious or vulnerable on-chain code.

Rogue Smart Contracts: Interactions that trigger hidden malicious code logic, leading to fund theft.

Flash Loan Attacks: Exploiting uncollateralized loans to manipulate prices or protocol logic.

Oracle Manipulation: Attackers tampering with price information to exploit protocols relying on erroneous data.

Exit Liquidity Scams: Creators design tokens/pools that only they can withdraw funds from, trapping users.

Witch Attacks: Using multiple fake identities to disrupt decentralized systems, especially governance or airdrop eligibility.

Project and Market Manipulation Scams

Scams related to tokens, DeFi projects, or NFTs.

Rug Pulls: Project founders disappear after raising funds, leaving worthless tokens.

Fake Projects: Fake NFT collections lure users into scams or signing harmful transactions.

Dusting Attacks: Using tiny token transfers to anonymize wallets and identify phishing or scam targets.

Network and Infrastructure Attacks

Exploiting the front-end or DNS-level infrastructure that users rely on.

Front-End Hijacking/DNS Spoofing: Attackers redirect users to malicious interfaces to steal credentials or trigger unsafe transactions.

Cross-Chain Bridge Vulnerabilities: Stealing user funds during cross-chain bridge transfers.

Physical Threats

Risks in the real world, including coercion, theft, or surveillance.

Personal Attacks: Victims are coerced into transferring funds or revealing mnemonic phrases.

Physical Theft: Stealing devices or backups (e.g., hardware wallets, notebooks) to gain access.

Shoulder Surfing: Observing or recording users inputting sensitive data in public or private settings.

Key Vulnerabilities to Note

While there are many ways users can be hacked, some vulnerabilities are more common. Here are three types of vulnerability attacks that individuals holding or using cryptocurrency should be most aware of, along with how to prevent them.

Phishing (Including Fake Wallets and Airdrops)

Phishing predates cryptocurrency by decades; the term emerged in the 1990s to describe attackers "fishing" for sensitive information (usually login credentials) through fake emails and websites. As cryptocurrency emerged as a parallel financial system, phishing naturally evolved to target mnemonic phrases, private keys, and wallet authorizations.

Cryptocurrency phishing is particularly dangerous because it lacks recourse: no refunds, no fraud protection, and no customer service to reverse transactions. Once your keys are stolen, your funds are essentially gone. It is also important to remember that phishing is sometimes just the first step in a larger attack, and the real risk is not the initial loss, but the subsequent series of damages, such as stolen credentials allowing attackers to impersonate victims and deceive others.

- How does phishing work?

At the core of phishing is the exploitation of human trust, enticing users to voluntarily hand over sensitive information or approve malicious actions by presenting a false trustworthy interface or impersonating authority figures. The main dissemination methods include:

Phishing websites

Fake versions of wallets (e.g., MetaMask, Phantom), exchanges (e.g., Binance), or dApps

Typically promoted through Google Ads or shared via Discord/X groups, designed to appear consistent with real websites

Users may be prompted to "import wallet" or "recover funds," thereby stealing their mnemonic phrases or private keys

Phishing emails and messages

Fake official communications (e.g., "urgent security update" or "account compromised")

Links to fake login portals or guiding users to interact with malicious tokens or smart contracts

Some phishing attempts even allow you to deposit funds, but the funds will be stolen minutes later

Airdrop scams, sending fake token airdrops to wallets (especially on EVM chains)

Clicking on tokens or attempting to trade tokens triggers malicious contract interactions

Secret requests for unlimited token approvals or stealing users' native tokens through signed payloads.

Phishing Case

In June 2023, the North Korean Lazarus Group attacked Atomic Wallet, marking one of the most destructive pure phishing attacks in cryptocurrency history. The attack compromised over 5,500 non-custodial wallets, resulting in the theft of over $100 million in cryptocurrency, all without requiring users to sign any malicious transactions or interact with smart contracts. This attack extracted mnemonic phrases and private keys solely through deceptive interfaces and malware— a typical case of credential theft based on phishing.

Atomic Wallet is a multi-chain non-custodial wallet supporting over 500 cryptocurrencies. In this incident, the attackers launched a coordinated phishing campaign that exploited users' trust in the wallet's supporting infrastructure, update processes, and brand image. Victims were lured by emails, fake websites, and trojan software updates, all designed to mimic legitimate communications from Atomic Wallet.

The phishing methods employed by the hackers included:

Fake emails disguised as Atomic Wallet customer support or security alerts urging users to take urgent action.

Deceptive websites mimicking wallet recovery or airdrop claiming interfaces (e.g.,

atomic-wallet[.]co).Distributing malicious updates via Discord, email, and infected forums, which either directed users to phishing pages or extracted login credentials through local malware.

Once users entered their 12 or 24-word mnemonic phrases on these fraudulent interfaces, the attackers gained full access to their wallets. This vulnerability required no on-chain interaction from the victims: no wallet connection, no signature requests, and no smart contract involvement. Instead, it relied entirely on social engineering and the users' willingness to recover or verify their wallets on seemingly trustworthy platforms.

Wallet Stealers and Malicious Authorizations

Wallet stealers are malicious smart contracts or dApps designed to extract assets from user wallets, not by stealing private keys, but by tricking users into authorizing access to tokens or signing dangerous transactions. Unlike phishing attacks (which steal user credentials), wallet stealers exploit permissions—the very core of the Web3 trust mechanism.

As DeFi and Web3 applications became mainstream, wallets like MetaMask and Phantom promoted the concept of "connecting" dApps. This brought convenience but also significant attack vulnerabilities. From 2021 to 2023, NFT minting, fake airdrops, and some dApps began embedding malicious contracts into otherwise familiar user interfaces, leading users to connect their wallets and click "approve" out of excitement or distraction, often unaware of what they were authorizing.

- Attack Mechanism

Malicious authorizations exploit the permission systems in blockchain standards (e.g., ERC-20 and ERC-721/ERC-1155). They trick users into granting attackers ongoing access to their assets.

For example, the approve(address spender, uint256 amount) function in ERC-20 tokens allows a "spender" (e.g., a dApp or attacker) to transfer a specified amount of tokens from the user's wallet. The setApprovalForAll(address operator, bool approved) function in NFTs grants the "operator" permission to transfer all NFTs in a collection.

These approvals are standard configurations for dApps (e.g., Uniswap requires approval to swap tokens), but attackers maliciously exploit them.

- How Attackers Gain Authorization

Deceptive Prompts: Phishing websites or infected dApps prompt users to sign a transaction labeled "wallet connection," "token swap," or "NFT claim." This transaction actually calls the

approveorsetApprovalForAllmethod at the attacker's address.Unlimited Approvals: Attackers often request unlimited token authorizations (e.g.,

uint256.max) orsetApprovalForAll(true), thereby gaining complete control over the user's tokens or NFTs.Blind Signing: Some dApps allow users to sign opaque data, making malicious actions difficult to detect. Even hardware wallets like Ledger may display seemingly harmless details (e.g., "approve token") while hiding the attacker's intent.

Once attackers gain authorization, they may immediately use the authorization information to transfer tokens/NFTs to their wallets or wait (sometimes weeks or months) to steal assets, reducing suspicion.

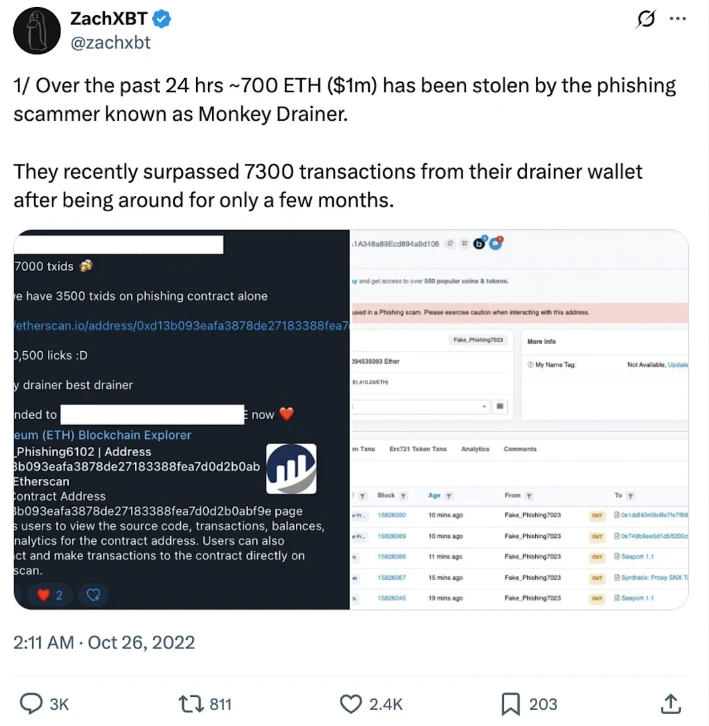

Wallet Drainer/Malicious Authorization Case

The Monkey Drainer scam primarily occurred in 2022 and early 2023. It is a notorious "drainer-as-a-service" phishing toolkit responsible for stealing millions in cryptocurrency (including NFTs) through deceptive websites and malicious smart contracts. Unlike traditional phishing that relies on collecting user mnemonic phrases or passwords, Monkey Drainer operates through malicious transaction signatures and smart contract abuse, allowing attackers to extract tokens and NFTs without directly stealing credentials. By tricking users into signing dangerous on-chain approvals, Monkey Drainer stole over $4.3 million from hundreds of wallets before shutting down in early 2023.

Famous on-chain detective ZachXBT exposed the Monkey Drainer scam.

This toolkit was popular among low-skilled attackers and heavily promoted in underground Telegram and dark web communities. It allowed affiliates to clone fake minting websites, impersonate real projects, and configure backends to forward signed transactions to centralized withdrawal contracts. These contracts were designed to exploit token permissions, signing messages without users' knowledge, granting the attacker's address access to the assets through functions like setApprovalForAll() (NFT) or permit() (ERC-20 tokens).

Notably, this interaction process avoided direct phishing, as victims were not asked to provide private keys or mnemonic phrases. Instead, they interacted with seemingly legitimate dApps, often on minting pages featuring countdowns or popular brand promotions. Once connected, users were prompted to sign a transaction they did not fully understand, often obscured by generic authorization language or wallet user interfaces. These signatures did not directly transfer funds but authorized the attacker to transfer at any time. Once authorized, the drainer contract could execute bulk withdrawals within a single block.

A key feature of the Monkey Drainer method is its delayed execution; stolen assets are typically withdrawn hours or days later to avoid raising suspicion and maximize profits. This made it particularly effective against users with large wallets or active trading activities, as their authorizations blended into normal usage patterns. Some notable victims included NFT collectors from projects like CloneX, Bored Apes, and Azuki.

Although Monkey Drainer ceased operations in 2023, the era of wallet drainers continues to evolve, posing an ongoing threat to users who misunderstand or underestimate the power of blind on-chain authorizations.

Malware and Device Vulnerabilities

Finally, "malware and device vulnerabilities" refer to a broader and more diverse range of attacks that encompass various dissemination media aimed at infiltrating users' computers, phones, or browsers to install malware through deception. Their goal is typically to steal sensitive information (e.g., mnemonic phrases, private keys), intercept wallet interactions, or allow attackers to remotely control the victim's device. In the cryptocurrency field, these attacks often begin with social engineering, such as fake job opportunities, fake application updates, or files sent via Discord, but quickly escalate into full system intrusions.

Malware has existed since the inception of personal computers. Traditionally, it was used to steal credit card information, collect login details, or hijack systems to send spam or ransomware. With the rise of cryptocurrency, attackers have shifted their focus from online banking to stealing irreversible crypto assets.

Most malware does not spread randomly; it requires victims to be tricked into executing it. This is where social engineering comes into play. Common dissemination methods have been listed in the first section of this article.

Malware and Device Vulnerabilities Case: 2022 Axie Infinity Recruitment Scam

The 2022 Axie Infinity recruitment scam led to a massive Ronin Bridge hack, serving as a typical case of malware and device vulnerability exploitation in the cryptocurrency field, backed by complex social engineering tactics. This attack was attributed to the North Korean hacking group Lazarus, resulting in the theft of approximately $620 million in cryptocurrency, making it one of the largest decentralized finance (DeFi) hacks to date.

The Axie Infinity vulnerability was reported by traditional financial media.

This hacking incident was a multi-stage operation that combined social engineering, malware deployment, and exploitation of blockchain infrastructure vulnerabilities.

The hackers impersonated recruiters from a fictitious company, targeting employees of Sky Mavis, the operating company of the Ronin Network, through LinkedIn. The Ronin Network is a sidechain associated with Ethereum that supports the popular "play-to-earn" blockchain game Axie Infinity. At the time, Ronin and Axie Infinity had market capitalizations of approximately $300 million and $4 billion, respectively.

The attackers contacted multiple employees, but their primary target was a senior engineer. To build trust, the attackers conducted multiple rounds of fake job interviews and offered an extremely generous salary to entice the engineer. They sent this engineer a PDF document disguised as a formal job offer. The engineer mistakenly believed this was part of the recruitment process and downloaded and opened the file on the company computer. The PDF contained a RAT (Remote Access Trojan) that, once opened, compromised the engineer's system, allowing the hackers to access Sky Mavis's internal systems. This breach set the stage for attacking the Ronin Network's infrastructure.

The hack resulted in the theft of $620 million (173,600 ETH and $25.5 million USDC), with only $30 million ultimately recovered.

How Should We Protect Ourselves

Although vulnerability attacks are becoming increasingly complex, they still rely on some obvious signs. Common danger signals include:

“Import your wallet to claim X”: No legitimate service will ask you for your mnemonic phrase.

Unsolicited direct messages: Especially those claiming to offer support, funds, or solutions to problems you did not inquire about.

Slight misspellings in domain names: For example, metamusk.io vs. metarnask.io.

Google ads: Phishing links often appear above legitimate links in search results.

Offers that are too good to be true: For example, “Claim 5 ETH” or “Double token rewards” promotions.

Urgency or intimidation tactics: “Your account has been locked,” “Claim now or lose your funds.”

Unlimited token approvals: Users should set the token amount themselves.

Blind signing requests: Hexadecimal payloads lacking readable explanations.

Unverified or vague contracts: If the token or dApp is new, check what you are approving.

Urgent UI prompts: Typical pressure tactics, such as “You must sign immediately or miss out.”

Unexplained MetaMask signature pop-ups: Especially in cases of unclear demands, gasless transactions, or function calls you do not understand.

Personal Protection Rules

To protect ourselves, we can adhere to the following golden rules:

Never share your mnemonic phrase with anyone for any reason.

Bookmark official websites: Always navigate directly, never use search engines to look for wallets or exchanges.

Do not click on random airdrop tokens: Especially for projects you have not participated in.

Avoid unsolicited direct messages: Legitimate projects rarely DM first… (unless they actually do).

Use hardware wallets: They can reduce the risk of blind signing and prevent key leaks.

Enable phishing protection tools: Use extensions like PhishFort, Revoke.cash, and ad blockers.

Use read-only browsers: Tools like Etherscan Token Approvals or Revoke.cash can show what permissions your wallet has.

Use disposable wallets: Create a new wallet with zero or minimal funds to test minting or links first. This will minimize losses.

Diversify assets: Do not keep all assets in one wallet.

If you are already an experienced cryptocurrency user, you can follow these more advanced rules:

Use dedicated devices or browser profiles for cryptocurrency activities, and also use dedicated devices to open links and direct messages.

Check Etherscan's token warning labels; many scam tokens have been flagged.

Cross-verify contract addresses with official project announcements.

Carefully check URLs: Especially in emails and chats, subtle spelling errors are common. Many instant messaging applications, and certainly websites, allow hyperlinks—this enables someone to click on links like www.google.com directly.

Pay attention to signatures: Always decode transactions before confirming (e.g., through MetaMask, Rabby, or emulators).

Conclusion

Most users believe that vulnerabilities in cryptocurrency are technical and inevitable, especially those new to the industry. While complex attack methods may indeed be so, often the initial steps target individuals in a non-technical manner, making subsequent attacks preventable.

The vast majority of personal losses in this field do not stem from some novel code vulnerabilities or obscure protocol flaws, but rather from people signing without reading documents, importing wallets into fake applications, or trusting a seemingly reasonable DM. These tools may be new, but their tricks are age-old: deception, urgency, and misdirection.

The self-custody and permissionless features are advantages of cryptocurrency, but users need to remember that such features also increase risks. In traditional finance, if you get scammed, you can call the bank; in cryptocurrency, if you get scammed, the game is probably over.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。