Editor’s Note: The complete content of this article comes from Redstone's "2025 Report on Yield-Generating Assets and Stablecoins," which attempts to construct a clearer qualitative classification framework for yield-generating stablecoins to help readers understand the true layering within the stablecoin ecosystem. Given the original report's length, Odaily Planet Daily has moderately condensed the overall content.

Driven by the GENIUS Act, the architecture of the digital asset economy is at a critical point of fundamental transformation. As a milestone piece of legislation, the act intentionally divides the stablecoin market into two categories: one is the "Payment Stablecoins," which are federally regulated, non-yielding, and payment utility-focused; the other is defined as investment assets, referred to as "Yield-Bearing Stablecoins" (YBS). Our core argument is that while this classification provides regulatory clarity for payment infrastructure, it simultaneously introduces a new and complex investment landscape, which the current market evidently lacks the capacity to address.

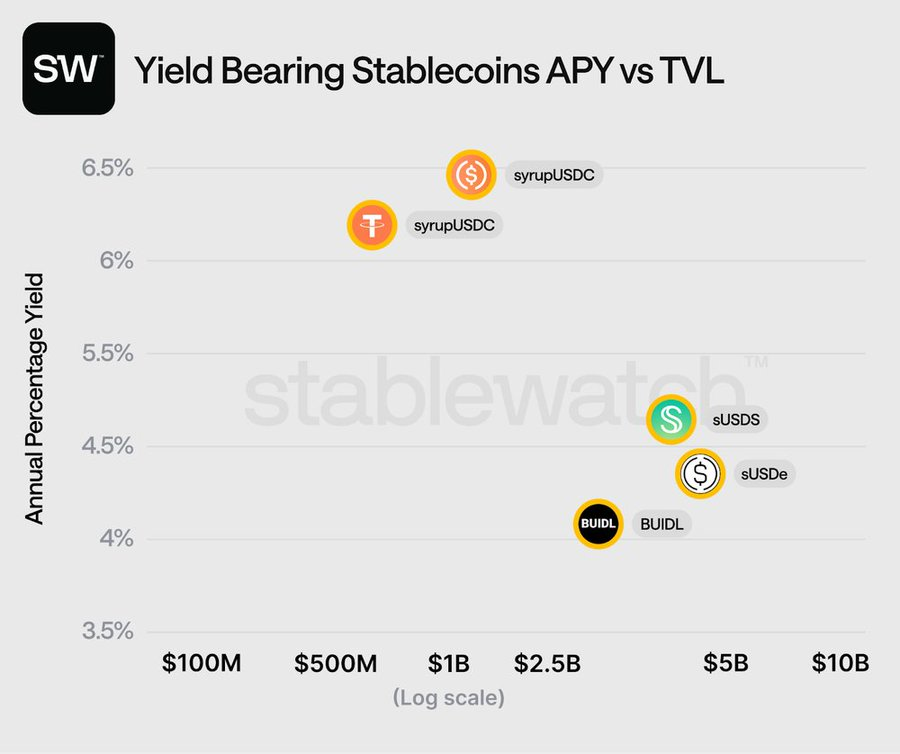

The core issue we aim to resolve is that the label "YBS" is too broad and dangerous. It conceals a vast spectrum of structures, risks, and underlying logics that are fundamentally different. For instance, a tokenized U.S. Treasury bond and a delta-neutral synthetic dollar can both be called YBS, but they share almost no commonality in terms of mechanisms, collateral, and risk characteristics. Whether for investors, protocols, or risk managers, relying solely on superficial APY comparisons between the two would lead to serious judgment errors.

To this end, this article creates a qualitative classification framework for the YBS ecosystem, deconstructing its structure and summarizing the key opportunities and risk vectors of each category, providing a foundation for mature and risk-sensitive investment decisions. This report not only analyzes surface-level indicators but also focuses on the most critical underlying differences: the sources and nature of returns.

In the following analysis, we categorize the YBS field into three main types. The first type is RWA-backed YBS, which "transfers" the yields generated by off-chain traditional financial assets (such as U.S. Treasury bonds) onto the blockchain. The second type is on-chain native YBS, where yields come from crypto-native economic activities such as lending and derivatives. The third type is actively managed YBS, where yields come from complex algorithms or human management, representing the forefront of on-chain financial engineering development.

We focus on these three main threads, although this classification is not perfect, as many YBS exhibit cross-category characteristics and composite risks. More refined classifications and key risk points for each asset can be found at https://app.stablewatch.io/. The following content will introduce the overall characteristics, representative projects, potential opportunities, and main risks of each category, and finally discuss how the emergence of assets like USDH is evolving the value capture model of stablecoins.

Main Business Areas of Yield-Generating Stablecoins

After the GENIUS Act, the stablecoin market requires a new understanding framework. In the past, stablecoins were an almost homogeneous field, with yield being an incidental attribute; now, it is deliberately segmented, and we need to shift from the single concept of "stablecoin" to a refined perspective based on risk and return. In this new reality, the framework must go beyond the superficial "whether it is pegged" and delve into where the yield comes from, as the source of yield determines the risk profile and economic function.

At the top of this framework is the first type: RWA-backed YBS. These tools can be understood as "transmission" tools for traditional financial (TradFi) yields. Their core mechanism is to channel the yields generated by off-chain institutional assets (primarily U.S. Treasury bonds) onto the blockchain for distribution to token holders. They sit at the most conservative end of the YBS risk spectrum, acting as a bridge between TradFi and the on-chain economy, providing yields in a familiar, low-credit-risk manner.

In the middle is the second type: On-chain Native YBS. As the engine of a decentralized economy, the yields of these assets come entirely from on-chain native activities. For example, decentralized lending income, LSD yields, or funding rate yields obtained through market-neutral hedging strategies in perpetual contract markets. Their yields have a lower correlation with traditional markets, forming a new, autonomous path for capital appreciation.

At the end of the spectrum in terms of risk and complexity is the third type: Actively Managed YBS. Their yields do not come from passive returns of underlying assets but are generated through complex and dynamic strategies, including automated multi-protocol rebalancing strategies or human-managed on-chain credit funds. These assets have the potential for excess returns while also introducing model risk, manager risk, and other complex risks not present in other YBS categories.

RWA-backed YBS: Bridging Traditional Finance

To understand the core mechanism of RWA-backed YBS, we need to start with its legal and financial architecture. Typically, the issuer establishes a bankruptcy-remote SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) in a favorable jurisdiction, solely for holding the underlying assets, to isolate the operational risks of the issuing entity and create a foundational layer of security.

Capital flows between on-chain and off-chain: After investors purchase with stablecoins (like USDC), the SPV uses this digital capital to buy off-chain yield assets, primarily short-term U.S. Treasury bonds or Treasury money market funds. After the purchase is completed, the issuer mints corresponding on-chain YBS tokens at a 1:1 ratio, representing a claim on the underlying assets.

The current RWA YBS ecosystem is rapidly expanding, with representative projects including Ondo Finance (OUSG, USDY), Superstate's USTB, and Mountain Protocol's USDM. Although all three share off-chain collateral, they differ in legal structure, target users, and yield distribution methods.

One of the core risks of this model comes from the custody of the underlying assets. Unlike crypto assets held in smart contracts, RWA collateral is held by traditional regulated institutions (like BNY Mellon). The reliance on off-chain centralized custodians introduces traditional counterparty risk into the DeFi ecosystem—this is a trade-off made to gain the stability and deep liquidity of traditional financial markets.

This category is further subdivided due to differences in the yield distribution methods of Treasury bond yields:

- Rebase Model (e.g., USDM): The price is stabilized at $1, and yields are realized by algorithmically increasing the token balance in holders' wallets daily. The downside is a lack of compatibility with most DeFi protocols (poor composability), as these protocols are not designed to handle assets with dynamically changing balances.

- Net Asset Value Accrual (NAV Accrual) (e.g., OUSG): The number of tokens is fixed, while the net asset value (NAV) or redemption value of the tokens steadily increases with the accumulation of yields from the underlying assets. This method is natively compatible with all existing DeFi infrastructure, making it very suitable as collateral for lending markets and other applications.

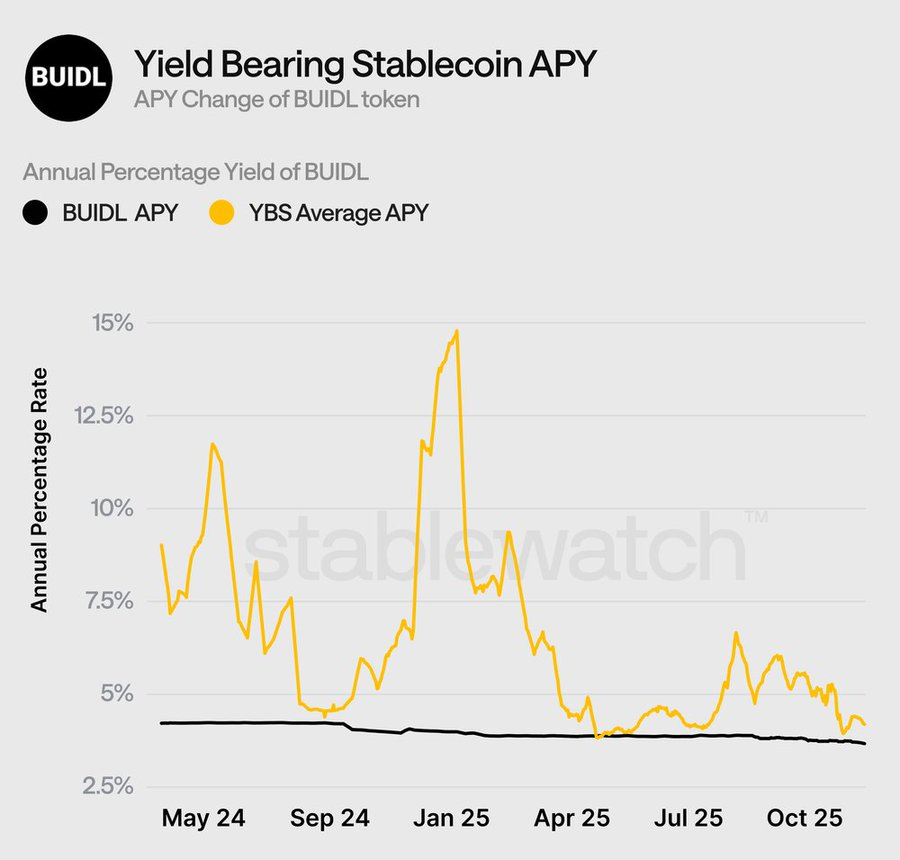

The most iconic is BlackRock's BUIDL, which is noteworthy as BUIDL is a tokenized share of BlackRock's existing money market fund. As an institutional-grade infrastructure for the industry, it is designed exclusively for qualified investors who pass KYC/AML.

A mature B2B2C supply chain is one of the most important developments in this field. Protocols like Ondo do not purchase Treasury bonds themselves but act as distributors and access layers, building products aimed at a broader user base on top of BUIDL.

RWA-backed YBS leverage the deep and stable yields of the global bond market, which exceeds $140 trillion, providing a familiar and relatively low-risk return model that is highly attractive to both crypto-native investors and traditional investors. Additionally, YBS offers a trustworthy and easy-to-understand entry point for traditional financial institutions looking to enter the digital asset space, backed by the credibility of large asset management firms like BlackRock.

However, the risks cannot be overlooked. The primary risks stem from counterparty risk and custody risk. The entire architecture relies on the solvency and operational integrity of off-chain banks, custodians, and SPV managers. Any failure in the off-chain reliance on any link in the chain could lead to partial or total loss of the underlying collateral.

Moreover, these tools also face significant regulatory risks. Many tools, such as BUIDL, are explicitly designed as registered securities and are subject to comprehensive constraints under securities laws. Therefore, they introduce a certain degree of regulatory friction and a series of compliance obligations, which are at odds with the permissionless philosophy of standard DeFi.

Another key factor is transparency risk. While issuers regularly provide proof and reports of off-chain reserves, there remains a significant gap compared to the real-time, verifiable transparency of on-chain collateral. Investors can only trust this periodically disclosed information without the ability to independently verify the collateral of their assets at any time.

Finally, these assets face liquidity risks. The promise of "instant" redemption for USDC often relies on a single, counterparty-funded smart contract. For example, in March 2025, the BUIDL-Circle redemption mechanism experienced a 23-hour availability limitation; once a single liquidity point fails, all redemptions will be forced back to the traditional financial system's T+1 or T+2 settlement cycle, reintroducing the friction that DeFi aims to eliminate.

On-Chain Native YBS: Portfolio Diversification Tools

In contrast to the model that relies on TradFi yields, the second type of yield-generating stablecoins entirely depends on the economic activities generated on-chain, thus having a weaker correlation with traditional finance and serving as an important diversification tool for portfolios.

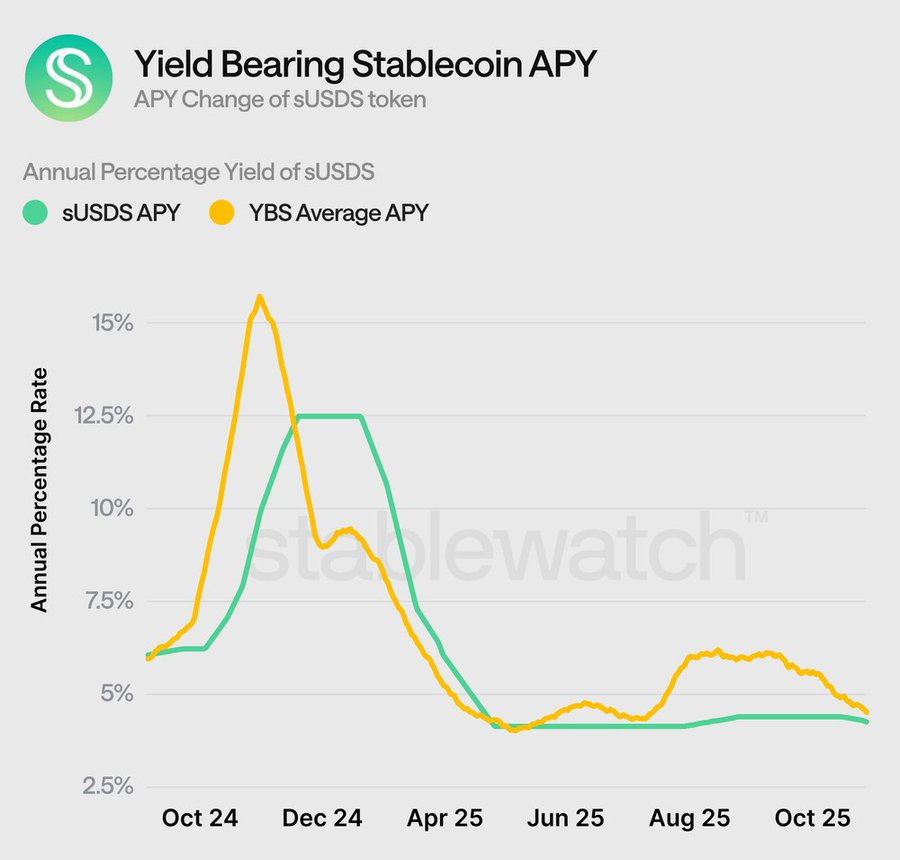

This category is mainly divided into three subtypes. The first subtype is the Yield Wrapper model, such as Sky Protocol's sUSDS. Users deposit non-yielding stablecoins like USDs into the protocol to receive sUSDS tokens, which appreciate in value as the protocol's income accumulates. The yields for sUSDS holders are generated by the entire Sky Protocol ecosystem, primarily from stable fees paid by borrowers and, crucially, from the yields generated by the protocol's multi-billion dollar RWA investments.

The second subtype is the Crypto Collateral (CDP) model. Users collateralize stablecoins by using crypto-native collateral (most commonly liquid staking tokens, such as stETH), with yields coming from the underlying staking rewards.

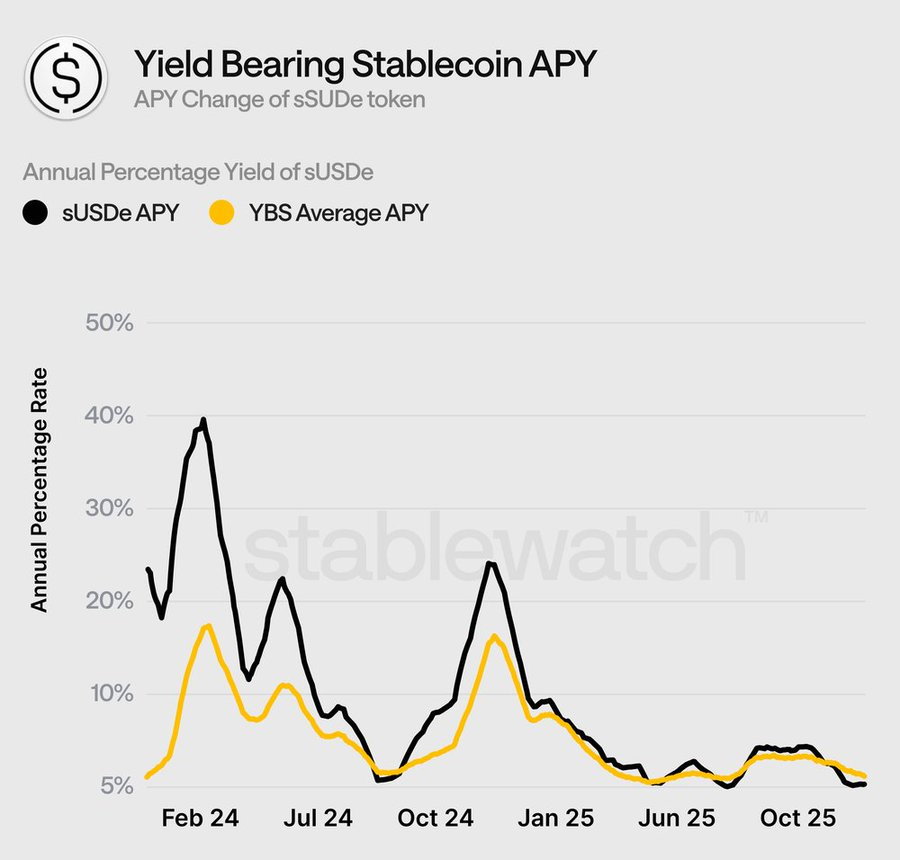

The third and most complex subtype is the Delta Neutral Strategy. This model generates yields not through collateral but through "spot-perpetual hedging" trades while maintaining the peg. The protocol simultaneously holds a long position in a certain crypto asset (like ETH) and a short position in the perpetual contract of the same asset, thus constructing a market-neutral position and earning yields from the funding rates paid by longs to shorts in the perpetual contract market.

The market for on-chain native yield-generating stablecoins is diverse, with typical projects including sUSDS, which distributes protocol income, and TBILL from OpenEden. The most representative case of a Delta Neutral strategy is Ethena's sUSDe, whose yields consist of LST yields + perpetual contract funding rates, making it a purely on-chain structured yield product.

The core value of on-chain native yield stablecoins lies in their low correlation with traditional financial markets, thus providing a source of yield that is unaffected by central bank monetary policy. Additionally, many such assets promise complete on-chain transparency, allowing anyone to audit their reserves and mechanisms in real-time, contrasting sharply with the opaque, proof-based RWA-backed stablecoins. This transparency, combined with their native composability, enables deep and efficient integration with a broader DeFi ecosystem.

The fundamental risk of these stablecoins lies in smart contract risk. The entire system relies on the security and integrity of the underlying code; once a smart contract has a vulnerability or is attacked, it could lead to total loss of funds, a risk that has always existed in the DeFi space.

Beyond the code itself, there is also economic model risk, which is the most significant and least understood vulnerability. Taking Ethena as an example, this risk manifests as a persistent negative funding rate—i.e., a reversal in market leverage demand, where shorts must pay longs. At this point, the supporting assets of the protocol will begin to erode, while the underlying LST yields can only partially buffer this risk.

Next is collateral risk. The stability of these protocols typically relies on the crypto assets used as collateral. For CDPs, the risk lies in the collateral (such as a certain LST) decoupling from its underlying asset. For Delta Neutral protocols, the risk is a sudden sharp decline in the spot collateral asset, while the perpetual contract price does not change synchronously, potentially triggering liquidation.

Finally, the Delta-Neutral model also involves counterparty risk from centralized exchanges. These protocols often rely on exchanges like Binance and Bybit to execute their short hedges. This means the protocol is exposed to potential operational risks, bankruptcy risks, fund freezing, or downtime risks from the exchanges—a typical "FTX scenario."

Actively Managed YBS: The Frontier of On-Chain Financial Engineering

The third type, actively managed YBS, represents the forefront of on-chain financial engineering, encompassing "black box" models within the yield-generating stablecoin world. Here, yields are no longer a passive transmission of returns from an underlying asset but are actively generated through dynamic and often opaque strategies. These models rely on active management, whether by humans or algorithms, to respond to market conditions and create excess returns.

These stablecoins are divided into two subcategories. The first subtype is algorithmic strategies, where automated systems deploy capital across multiple DeFi protocols and investment tools. These strategies execute complex trades based on predefined logic to capture yields from market inefficiencies, liquidity provision, or other special sources. Essentially, they function as autonomous on-chain hedge funds.

The second, and more common, subtype is human-managed strategies. More specifically, this approach reintroduces human decision-making to generate yields. It relies on experienced portfolio managers or credit underwriters to make proactive, autonomous decisions regarding the deployment path of capital on-chain. Effectively, this is akin to traditional actively managed fund structures being brought onto the blockchain.

Although the market for these advanced models is still in its early stages, several innovative protocols have emerged. A typical case is Maple Finance and its issued syrupUSDC and syrupUSDT.

Taking Maple's syrupUSDC as an example, we can see how this model operates in practice. syrupUSDC is an accumulating yield token that represents the funds users deposit into the Maple lending pool. The yields for holders come from the interest paid on unsecured and over-collateralized loans issued to institutional borrowers (such as crypto-native market makers and hedge funds) by the protocol.

The core of this mechanism, and the primary source of its unique risk structure, is the role of Pool Delegates. They are not algorithms but human fund managers approved and vetted by the Maple team, responsible for acting as on-chain credit underwriters. They must find and vet borrowers, conduct traditional off-chain due diligence, negotiate loan terms, and actively manage the loan portfolio, including handling default events.

The main value proposition of such strategies lies in their potential to generate excess returns. By breaking through the passive yields of T-bills (Treasury bonds) or staking, these active strategies can access higher yield opportunities, such as on-chain private credit and other alternative yield sources that general markets cannot participate in. This also allows us to glimpse a future where the role of active fund managers will be reshaped and disintermediated by on-chain frameworks.

However, the risk structure of this category is correspondingly higher and more complex. First is model risk; the underlying logic of these "black box" systems may be fragile, potentially over-optimized for past market conditions, or exposed to unforeseen utilization methods, leading to catastrophic failures.

For human-managed strategies, the main risk vectors are centralization and manager risk. The safety of yields and principal entirely depends on the skills, due diligence capabilities, and integrity of the human pool managers. A poor underwriting decision, improper risk management, or simple judgment error can lead to significant losses for lenders. Clearly, this model reintroduces the risk of "humans" at the core of DeFi protocols.

Complexity risk is a direct result of the first two. Whether algorithm-driven or human-managed, the complexity of these strategies makes it difficult for ordinary users to conduct comprehensive risk assessments. The sources of yield are often diverse, the risk exposures are dynamic, and potential failure points are numerous and often invisible.

The $36 million default event involving Orthogonal Trading on Maple Finance at the end of 2022 is a classic case of such risks. This event did not result from a failure of the smart contract; the Maple protocol itself was functioning well. The failure stemmed entirely from human factors: the pool manager M11 made due diligence and risk management errors while underwriting Orthogonal, leading to funds being lent to a borrower that was over-invested in FTX. Therefore, users depositing syrupUSDC were essentially betting not on the protocol code but on the underwriting ability of the pool manager.

Stablecoin Value Capture Heats Up

In the YBS ecosystem, the next stage of evolution no longer focuses solely on the assets themselves but extends to their underlying infrastructure. For high-throughput payment and trading scenarios, the future of stablecoins lies not in continuing to be deployed as applications on general-purpose blockchains but in becoming the native foundational assets of dedicated blockchains. The inherent limitations of general-purpose chains—such as fluctuating gas fees and probabilistic finality—are fundamentally at odds with the performance and certainty required for a global value transfer layer, and "stablecoin chains" are attempting to fundamentally address these issues.

Stablewatch has systematically elaborated on this argument in the “Stablecoin Chains” thematic report. Building on this foundation, this article will further extend this viewpoint by taking Hyperliquid's USDH yield capture mechanism as an example.

Hyperliquid adopts a completely reverse and unique market strategy: instead of starting with the construction of a general-purpose L1 and then waiting for developers and users to join, it first built a high-performance decentralized perpetual contract exchange and achieved strong product-market fit (PMF) in that vertical track. Only after the value of the infrastructure and the user scale were fully validated did it begin to open its self-developed L1, HyperEVM, for external developers to build the ecosystem. This can be described as a “product first, chain later” strategy, which effectively reduces the overall risk of launching L1 by prioritizing the product.

In this context, Hyperliquid's USDH has become a typical case for the argument of “stablecoin chains,” where stablecoins are no longer just an asset on the chain but exist as the economic core of the chain, forming a deep, symbiotic coupling relationship with the underlying infrastructure.

This design also circumvents the restrictions imposed by the GENIUS Act on payment stablecoins, which cannot generate yields. USDH itself is defined as yield-free to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements for payment tools. However, the billions of dollars in RWA reserves supporting USDH supply can still generate tens of millions of dollars in annual yields—though these yields are not distributed to USDH holders.

The real key is that this portion of the yield is designed to be absorbed by the Hyperliquid ecosystem itself. To compete for the issuance qualification of USDH, established stablecoin issuers such as Paxos and Agora promised in their bids to return 95-100% of the net reserve yields entirely to the Hyperliquid protocol, thereby validating the feasibility of this model. Although the winning team was Native Markets from within the ecosystem, their proposal also adhered to this principle: committing to return most of the reserve yields back to Hyperliquid to support the long-term development of the chain and the accumulation of native token value.

Ultimately, this results in a decentralized, DeFi-native, community-oriented yield capture mechanism—one that not only effectively addresses the yield distribution issue but also aligns the economic incentives of the stablecoin with the long-term healthy development of the underlying L1.

Conclusion

The primary impact of the GENIUS Act in 2025 is the successful differentiation of the stablecoin market. The act clarifies the role of “payment stablecoins” as purely functional tools that do not generate yields; at the same time, it pushes all yield-seeking activities into another independent, prosperous, but extremely broad-risk ecosystem of yield-bearing stablecoins (YBS). The core argument of this report is that the current market label “YBS” is too coarse and even misleading. It obscures a spectrum of risks that vary widely, and the market's understanding of these risk differences is just beginning.

The evolving YBS ecosystem presents a typical “apples and oranges” risk comparison dilemma for investors and protocols. The qualitative framework proposed in this report shows that the risks implied by various asset categories are neither explicit nor standardized, making them difficult to present transparently. Today's capital allocation is no longer a simple comparison of nominal APY but a systematic risk comparison assessment.

For example, for assets like OUSG, which are supported by RWA, is the custody and centralization risk more acceptable than the market and counterparty risks borne by “Delta Neutral protocols” like sUSDe? Or, is the risk brought about by “human management” in private credit funds (such as syrupUSDC) actually a more controllable trade? There are no standard answers to these questions.

The future growth of the YBS market, and even its long-term sustainability, entirely depends on whether the market can establish a more nuanced and risk-aware understanding to view these new financial primitives. The current mainstream still relies on simple quantitative metrics like TVL and APY, which completely overlook the “qualitative risk vectors” that truly define asset risks. To mature the market and attract institutional capital on a large scale, a new analytical infrastructure layer must be built.

The “GENIUS Act” is not merely a regulatory event but a starting gun—announcing the entry of on-chain financial innovation into a new era. With new models and complex risks, a new, more rigorous analytical paradigm is needed to understand them.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。