作者:赵启睿

编审:赵一丹

在后FTX时代的全球监管变局中,新加坡已完成其数字资产战略的根本性重塑。这一转型标志着其国家战略焦点已从一个包容零售投机的「加密货币天堂」(Crypto Haven),彻底转向一个「全球机构资产堡垒」,其核心战术则是在严苛的监管壁垒下,精准筛选并引导资本流向机构级、高合规性的应用——尤其是现实世界资产(RWA)的代币化。

为实现这一目标,新加坡金融管理局(MAS)正遵循「拥抱数字资产创新,拒绝加密货币投机」的原则,刻意制造一种核心张力:一方面,它以「守护者计划」(Project Guardian)为旗帜,联合摩根大通、汇丰等全球金融巨头,积极抢占下一代金融市场基础设施(FMI)的主导权;另一方面,它通过对数字支付代币(DPT)服务商实施严厉的客户资产隔离与禁止零售借贷等「补丁」政策,并辅以全新的数字代币服务提供商(DTSP)跨境监管框架,将金融稳定风险与监管套利空间压缩至极限。这场战略取舍的最终目标清晰而坚定:放弃「零售交易中心」的桂冠,全力争夺全球「机构创新与治理中心」的主导权。

这一战略转向并非遥远的蓝图,而是由一系列关键政策催化的即时现实——其紧迫性,正由日历上步步紧逼的最后期限所定义,包括已正式落地的MAS稳定币监管框架,以及必须在2025年6月30日前强制执行的DTSP跨境框架。

因此,本文将用50000字左右的篇幅,旨在为全球四类核心决策者,绘制出一份不可或缺的实操与战略指南:它为全球项目方与企业,精准导航如何穿越MAS严苛的技术风险管理(TRM)要求与牌照审批的「潜规则」;为投资机构与资本分配者,深度揭示严苛监管所创造的「护城河」价值,并标定出高潜力RWA项目的投资坐标;为法律与合规专业人士,构建起一份关于《支付服务法》(PSA)与《证券期货法》(SFA)界定、乃至新加坡国际商业法庭(SICC)最新判例的严谨法律论证;更为政策研究者,提供了一份解码新加坡如何在金融创新与风险管控的钢丝上取得动态平衡的国家级战略分析范本。

RWA研究院荣誉发布「全球RWA合规风貌总览」系列深度研究报告。「全球RWA合规风貌总览系列」旨在针对美国、中国香港、新加坡、阿联酋迪拜、泰国、德国等世界主要监管国家/地区加密货币的监管法律政策、主要地区项目、协议技术搭建及架构设计等进行研究,试在为读者们带来深刻而全面的认识。

这是我们系列文章的第三篇。本篇篇幅较长,将会以三篇的形式投送。

第一部分

导论

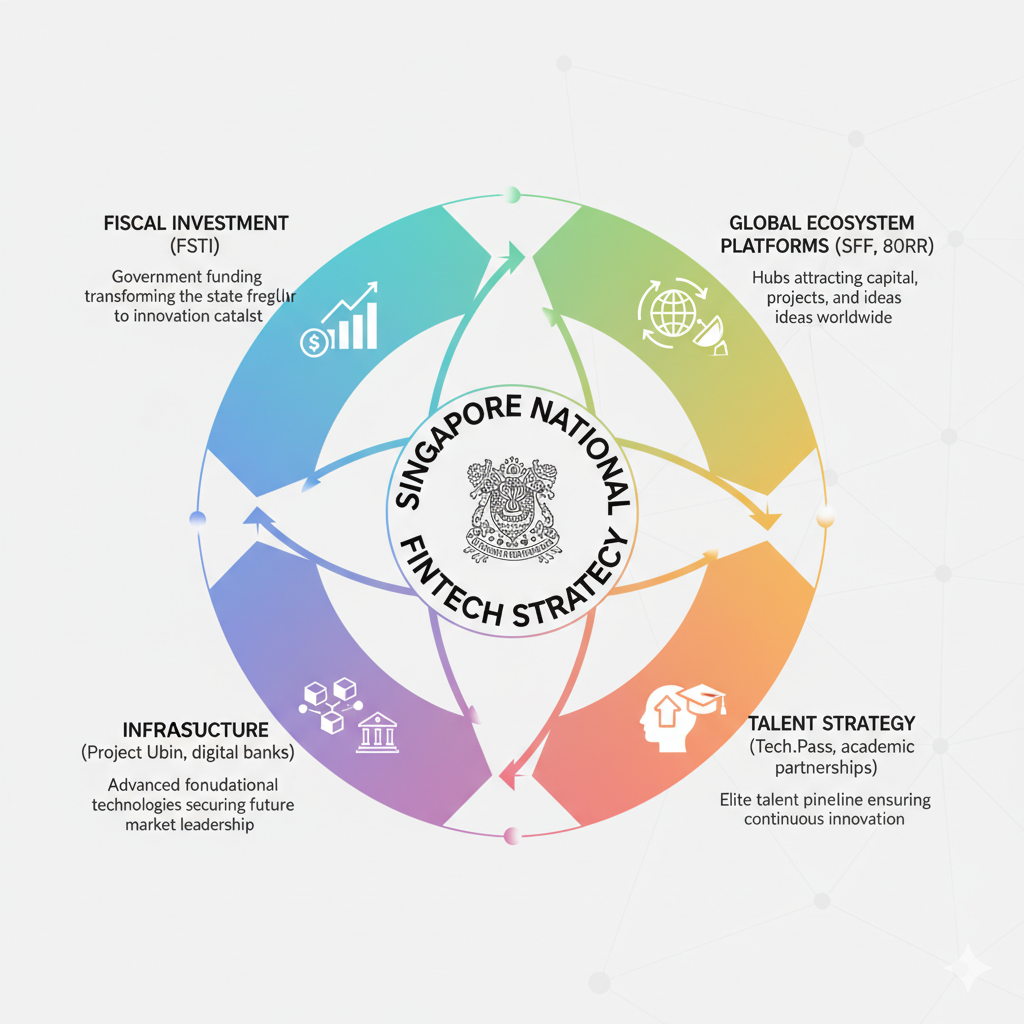

1.1新加坡的国家级金融科技战略

要精准理解新加坡在数字资产领域采取的每一个行动——无论是对加密货币的严格零售限制,还是对合规稳定币的积极接纳——都必须将其置于一个更宏大、更具前瞻性的背景下审视。这些行动并非孤立的市场反应,而是其长期、系统化、且雄心勃勃的「智能金融中心」国家战略的必然延伸。这一战略的核心在于,通过国家意志的直接驱动,构建一个从资金、人才、生态到基础设施的立体化创新体系,从而将新加坡定位为全球金融科技版图上不可或缺的核心节点。

政策输血

在推动金融科技创新的进程中,新加坡政府的角色远超传统的「监管者」,它更是一个积极的「催化剂」与「首席风险投资人」。这种国家意志最直接的体现,便是通过持续、大规模的财政投入来实现。

其核心驱动力是金融部门技术与创新计划(FSTI),这项由新加坡金融管理局(MAS)主导的计划,旨在加速和强化金融领域的创新。自2015年以S$2.25亿的五年承诺启动FSTI 1.0以来,这项投入已持续加码和升级。截至2015年,金融部门发展基金(FSDF)就已经通过FSTI计划奖励了S$3.4亿的资金,用于推动技术采纳和创新;

而最新的FSTI 3.0计划于2023年8月更新,承诺在未来三年内再投入高达S$1.5亿,重点支持新兴技术项目或具有区域关联的项目。该计划包括新的轨道,例如「创新加速轨道」,以支持Web 3.0等新兴技术带来的创新金融科技解决方案;以及「ESG金融科技轨道」,以满足金融业在ESG数据、报告和分析方面的需求。MAS甚至在2024年7月为此计划额外拨款S$1亿,专门用于支持金融机构在量子计算和人工智能(AI)领域的能力建设。

这种「真金白银」的系统性投入,辅之以如先锋证书激励/发展与扩展激励(PC&DEI)等长达15年的企业所得税豁免政策,清晰地表明:新加坡不仅是设定规则的监管者,更是通过财政激励来塑造行业发展方向、降低早期创新风险的首席风险投资人。

生态系统建设

这股强大的财政力量被精准地注入到一个旨在创造物理密度和思想化学反应的创新生态系统。

这个系统的战略舞台,便是全球最大规模的年度金融科技盛会——新加坡金融科技节(SFF)。这场汇集了来自134个国家和地区、超过65,000名参与者、900多位演讲嘉宾和600多家参展商(基于2025年的数据)的盛会,已成为新加坡向全球设定议程、输出影响力的核心平台。

在这里,MAS发布重大政策,并通过「资本与政策对话」(CMPD)等活动,旨在连接高级决策者和主要资本提供者,同时设有「创始人峰会」(Founders Stage)和「全球金融科技加速器」(GlobalFinTechHackcelerator)等,以支持早期创新和创业精神。

与此同时,像由香港置地与新加坡金融科技协会(SFA)共建的80 Robinson Road(80RR)创新中心,则通过在中央商务区提供可负担的物理空间,加速了初创企业、资本与监管者之间的协作。这个精心构建的生态系统,成功地将新加坡塑造为一个全球「引力场」,它通过MATCH等平台高效对接项目与资本,吸引了Antler等顶级早期投资者的入驻,其结果是,新加坡在2023年前九个月便吸纳了东盟地区59%的金融科技投资,形成了一个资本、项目与人才之间不断自我强化的正向循环,极大地增强了新加坡作为亚洲金融科技中心的地位。

人才培养与引进

一个充满资本与机遇的活力生态,必然会对最关键的生产要素——智力资本——产生巨大的需求。新加坡深谙此道,其人才战略采取了「内部培养」与「外部引进」并重的双轨策略。

在内部,它与新加坡国立大学(NUS)等顶尖学府合作,开设理学硕士(数字金融科技)课程(MScDFinTech),帮助学生在计算和金融领域建立坚实基础,并设有计算技术、金融数据分析与智能以及数字金融交易与风险管理等追踪方向。并与本地理工学院合作,设立亚洲数字金融学院(AIDF)等机构,每年目标培养2500名行业新生力量,旨在牵头金融科技教育和研究。

而在外部,它则更为主动,通过科技准证(Tech.Pass)和海外网络与专业知识准证(ONE Pass)等高门槛签证计划,在全球范围内精准「招揽」那些已被市场验证过的技术领袖与商业巨擘。

Tech.Pass的目标极为明确,它所吸引的并非普通技术人员,而是那些曾在估值超过5亿美元或融资额超过3000万美元的知名科技企业中担任过领导职务的、能够为本地生态系统带来核心经验与全球网络的技术精英和管理专家。Tech.Pass持有人还享有极大的灵活性,可以在没有雇主担保的情况下申请,并可同时从事多种经济活动,例如创办和运营一家或多家科技公司、担任员工、顾问、董事或在本地高等教育机构授课。

此外,海外网络与专业知识准证(ONE Pass)于2023年推出,旨在吸引所有行业(包括科学与技术)的顶尖人才,提供更长的5年有效期和高度的工作灵活性。这些签证计划旨在建立一个可持续的、金字塔形的人才梯队。通过Tech.Pass和ONE Pass,新加坡不再只是被动等待人才,而是主动招揽那些已被验证能为本地生态系统带来核心经验和技术诀窍的技术精英和管理专家。

「先修路,再跑车」

这整个由资本、社区和人才构成的宏大上层建筑,稳固地运行在一个由国家提前铺设的、具有前瞻性的数字基础设施之上。

新加坡的战略耐心,体现在其「先修路,再跑车」的深层思维。早在2016年,由MAS主导的Project Ubin便已开始对使用分布式账本技术(DLT)清算和结算支付与证券进行奠基性探索,这一早期实践为新加坡后续监管更复杂的央行数字货币(CBDC)和RWA代币化积累了宝贵的监管认知。随后的Project Orchid则延续了这一探索。与此同时,早在2019年就宣布发放的多达五张新的数字银行牌照(包括数字全银行牌照和数字批发银行牌照),更是一次意义深远的战略布局。此举的真正目的,并非仅仅引入竞争,而是要主动拥抱新的商业范式,以此作为「催化剂」,倒逼整个传统金融体系进行深度的数字化转型。

因此,新加坡在数字资产领域的审慎但前瞻性的监管路径——积极拥抱机构级资产代币化(RWA),同时对投机性加密货币实施严格的零售限制——绝非偶然,它是其立体化、全方位国家金融科技战略的必然结果。

这四大支柱——持续且加码的国家财政投入、全球规模的生态平台、精英化的人才战略以及前瞻性的基础设施建设——并非孤立的政策,而是一个紧密耦合、相互加强的国家级系统工程:持续且加码的国家财政投入(FSTI),将政府从监管者转变为创新催化剂;全球规模的生态平台(SFF和80RR),为资本、项目和思想交流提供不可或缺的引力场;精英化的人才战略(Tech.Pass和教育合作),确保创新所需的智力资本供给源源不绝;以及前瞻性的基础设施建设(Project Ubin和数字银行),通过抢先在底层技术进行部署来确保未来的市场主导权。

正是这个深思熟虑的顶层设计,为我们接下来将要深入剖析的、看似矛盾的「二元」监管理念提供了坚实的逻辑基础和战略支撑,也为新加坡争夺下一代全球机构级金融创新与治理中心的地位,奠定了极其深厚的基石。

1.2 监管的哲学与基石

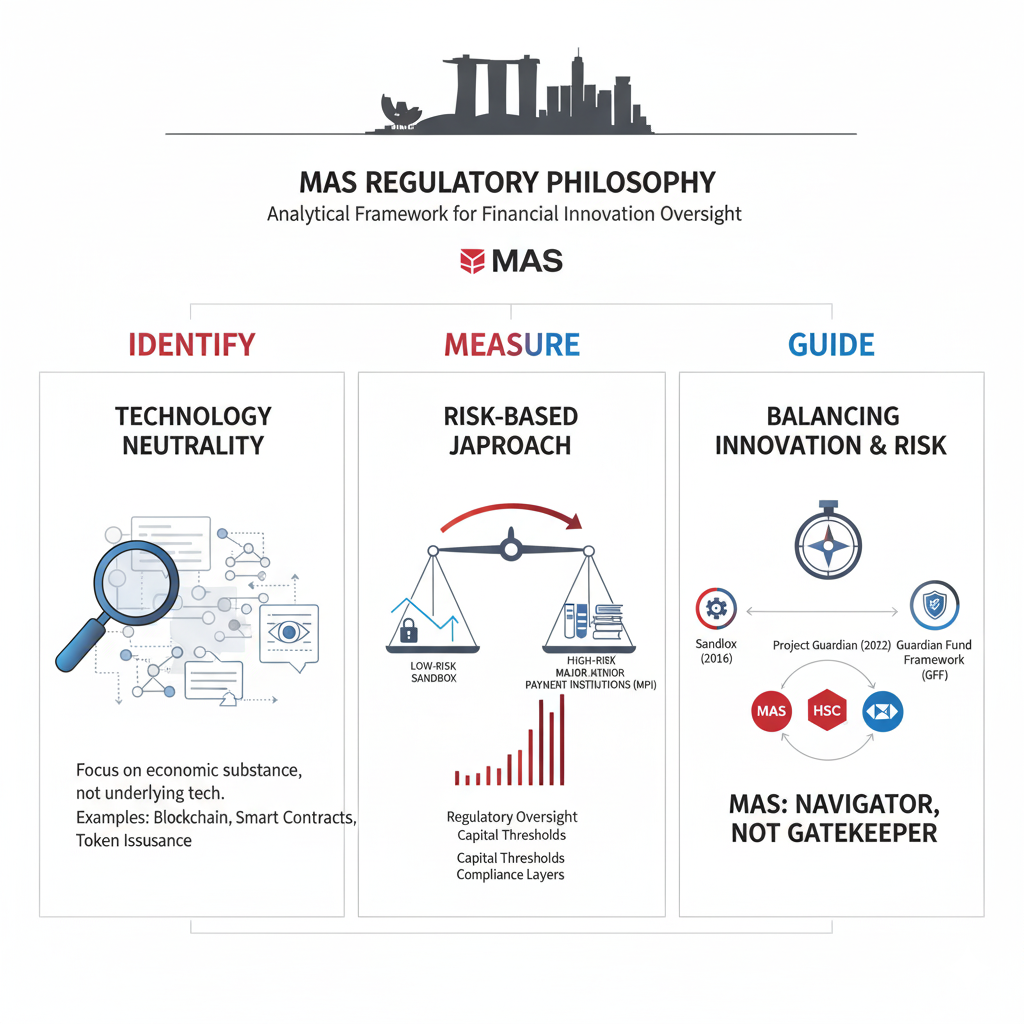

在宏大的国家级金融科技战略之下,新加坡能够进行审慎但高效的战略转型,其成功的基石在于新加坡金融管理局(MAS)成熟而独特的监管理念。

MAS集中央银行、综合金融监管和金融发展职能于一身,其监管行为绝非被动或零散的反应,而是遵循一套内在统一、逻辑自洽的哲学原则。这套理念构成了其监管框架的三大支柱,共同揭示了MAS面对任何金融创新时,是如何通过一套严密的思维过程进行识别、度量与引导的。

技术中立性

这套思维过程的第一步,是通过「技术中立性」原则进行识别。这是MAS面对纷繁创新时的第一道「分拣门」,其核心在于,监管的焦点永远是金融活动及其经济实质,而非底层采用的技术本身。MAS不为「区块链」或「分布式账本技术」(DLT)本身制定法律;相反,它采取「实质重于形式」的原则,穿透技术载体的表象,专注于该技术所承载的经济活动。

正如监管机构不监管「互联网」,但会监管在互联网上发生的「电子商务」与「在线支付」,MAS监管的也不是「智能合约」或「数字代币」这些技术名词,而是利用这些技术提供的「支付服务」、「资产托管」或「证券发行」等金融活动。

这一原则的实施,直接决定了项目将落入哪一部法律的管辖范围:

若代币具备证券属性,如果一个数字代币的结构、特征和赋予持有者的权利,使其具备了传统金融工具(如股权、债权、集体投资计划单位)的属性,即被认定为「资本市场产品」,则该代币的发行、交易和中介服务将受到《证券及期货法》(SFA)的严格监管;

若其主要用于支付,则提供相关服务的实体必须遵循《支付服务法》(PSA)的核心要求。因此,项目方不能以技术新颖为借口规避监管,对其代币的经济实质进行自我评估,是所有合规路径的起点。

风险为本

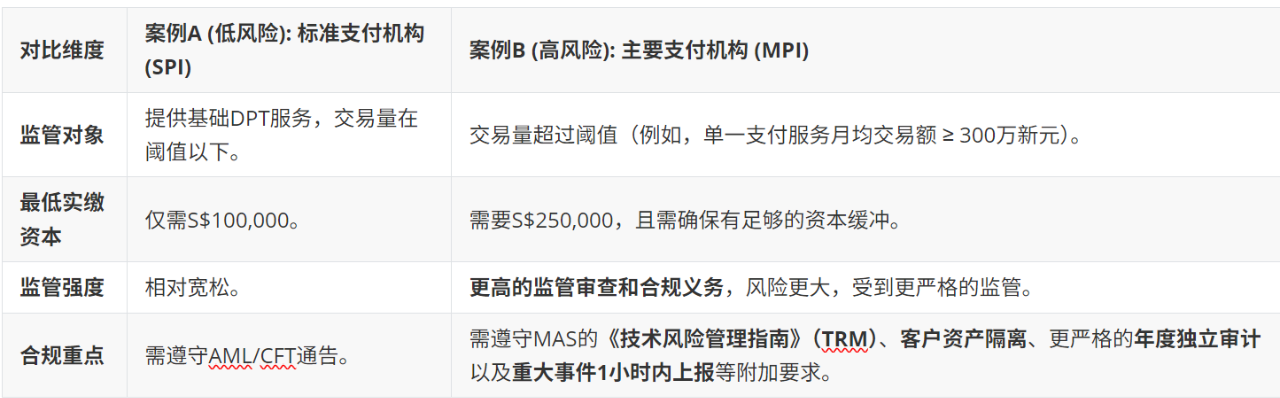

在识别了活动的金融本质后,思维过程便进入第二步:以「风险为本」的原则进行度量。这一原则是MAS用以分配监管资源、避免「一刀切」的智慧,其核心是:监管的强度、深度和复杂度,必须与一项业务所带来的潜在风险成正比。

MAS对金融机构进行分类管理,通过其综合风险评估框架(CRAFT)来评估机构的系统重要性,因为高影响的机构一旦出现问题,将对整个金融市场造成破坏性影响。这一原则在数字资产领域的PSA牌照体系中体现得淋漓尽致。对于业务规模尚在阈值之下的标准支付机构(SPI),MAS仅设定了10万新元的资本门槛;然而,一旦单一支付服务的月均交易额超过300万新元,升级为主要支付机构(MPI)后,监管的「火力」便会指数级增强,资本要求跃升至25万新元。

更重要的是,MPI必须遵循严苛的《技术风险管理指南》(TRM)、实施客户资产的法定信托隔离、接受更严格的年度独立审计,并在发生重大事件时于1小时内上报。这种差异化的监管强度,使得监管资源能够精准地集中于最关键的风险点,同时,对于风险较低的早期创新活动,例如通过快捷沙盒机制,MAS也为风险较低的早期创新保留了生存空间。

促进创新和风险的平衡

最后,在识别性质并度量风险之后,MAS的行动由其最终的「指南针」所指引:在促进创新与管控风险之间取得动态平衡,从而实现主动引导。

MAS的最终目标肯定不只是一个消极的「守门员」,而更应当是一个积极的「领航员」,旨在主动催化那些对经济有益的金融创新。这一哲学体现在其监管工具的不断进化中。自2016年推出的金融科技监管沙盒机制,是其早期「被动学习」的模式,它通过提供一个「安全实验区」,在降低创新者试错成本的同时,也让MAS能够近距离学习和理解新兴技术,为未来的法规制定积累第一手经验。

而「守护者计划」(Project Guardian)则标志着MAS从被动观察向主动塑造的决定性进化,可被视为「沙盒2.0」。该计划超越了被动等待申请的模式,由MAS主动设定议程(如资产代币化),并联合摩根大通、汇丰等全球金融巨头共同探索和「编写未来的规则手册」,催生了《守护者基金框架》(GFF)等行业标准。

这一积极举措清晰地向市场传递了信号:MAS鼓励的是能提升金融市场效率、解决实体经济痛点的「好创新」(如RWA和机构级应用),而非纯粹的、高波动性的投机活动。

综上所述,新加坡对数字资产的监管体系,是其国家级金融科技战略与其成熟监管理念的完美结合。技术中立性原则作为监管的边界,定义了「监管什么」;风险为本原则作为监管的强度,决定了「如何监管」;而平衡创新与风险的原则作为监管的方向,指明了「为何监管」。这三大基石相互支撑、逻辑自洽,共同构成了一个既严格又灵活、既审慎又前瞻的监管框架。对这套「MAS思维模式」的深刻理解,是所有市场参与者在新加坡生态中制定长期战略、实现合规成功的关键。

1.3 从「中心」到「枢纽」的战略转型

「在TOKEN2049人声鼎沸、亚洲Web3狂热聚集的背后,新加坡真的还是那个对所有加密货币参与者都敞开怀抱的‘天堂’吗?」 答案是否定的。表面现象与国家战略之间存在深刻的脱节。

我们需要说明:新加坡已不再是那个对所有参与者都敞开怀抱的加密「天堂」。这个国家正在进行一场深刻的「战略大挪移」:清醒地放弃成为一个以交易量和项目数量为标志、包容零售投机的「交易中心」(Center),转而全力争夺一个以规则制定、技术标准和机构级应用为主导的、高附加值的「战略枢纽」(Hub)的主导权。这不是一次简单的政策微调,而是在危机催化下,一次极具魄力且不可逆转的战略抉择。

转型的催化剂是2022年末三箭资本和FTX等大型加密机构崩溃所引发的全球性「雷曼时刻」。这些事件如同一面棱镜,残酷地折射出将国家声誉与一个开放但混乱的「广场集市」捆绑所带来的巨大风险。

当FTX的暴雷直接威胁到新加坡作为顶级金融中心的声誉,甚至使其主权财富基金淡马锡蒙受损失时,战略的转折点便已到来。MAS的反应并非恐慌,而是一系列基于其核心监管理念的、冷静而果断的战略回应。限制零售广告、强制客户资产隔离、禁止散户借贷等措施,是其迅速构筑的防御工事。

而最具决定性的一步,则是通过《金融服务与市场法》(FSMA)引入数字代币服务提供商(DTSP)牌照制度,要求所有在新加坡注册或运营的加密服务商,无论客户身在何处,都必须在2025年6月30日前获得许可。这一规定,彻底终结了「在新加坡注册、服务海外客户」的监管套利路径。

一系列行动,共同构成了一次主动的、有管理的战略放弃——新加坡清醒地认识到,管理一个混乱「广场集市」所带来的声誉风险,已远超其收益。

然而,从一个战场的战略性后撤,恰恰是为了在另一个更具决定性的战场上发动全力总攻。在主动收紧零售投机闸门的同时,新加坡将所有腾出的战略空间与政策资源,加倍下注于其新角色的构建——成为全球「机构创新与治理枢纽」。

这一新角色的物质体现,还是要回到其旗舰项目「守护者计划」(Project Guardian)上。该计划由MAS主导,联合了摩根大通、星展银行、汇丰、渣打银行、瑞银以及国际评级机构标普全球等全球顶级金融巨头,其核心焦点正是现实世界资产(RWA)的代币化。

新加坡的雄心不止于参与创新,更在于制定未来数字金融世界的「游戏规则」。通过Project Guardian,它正积极建立共同的信任层(Common Trust Layer),使用信任锚(Trust Anchors)(即受监管金融机构)来筛选和验证 DeFi 协议的参与者。同时,MAS已与行业共同发布《守护者基金框架》(GFF)和《守护者固定收益框架》(GFIF)等行业蓝图,为代币化资产的互操作性制定标准。

同时,严苛的DTSP牌照要求(如必须符合严密的技术风险管理(TRM)要求、客户资产隔离、以及对本地实质性运营和「机构基因」的偏好),正将「新加坡牌照」锻造成为全球数字资产领域信誉的黄金标准。而其完善的法律框架与高效的司法系统,特别是享有全球声誉的新加坡国际商业法庭(SICC),则为其成为解决复杂数字资产纠纷的首选仲裁地奠定了基础。

这种「扬此抑彼」(扬机构创新,抑零售投机)的做法,正是我们在上一章所分析的MAS监管哲学的最强有力证明。它较好地体现了「促进创新与管控风险的平衡」原则,即利用Project Guardian这样的「主动探索模式」明确鼓励「好创新」,同时坚决将高波动性的投机活动隔离于主流金融体系之外。

新加坡的数字资产战略转型,是一次「质」取代「量」的深刻变革。它甘愿放弃作为一个人人都能参与的「广场集市」(交易中心)的地位,因为这种模式带来了难以控制的风险。相反,它正致力于成为一个门槛虽高、但规则明确、服务于全球顶级金融玩家的「中央银行家俱乐部」(战略枢rayed)。这个「枢纽」将聚焦于通过Project Guardian等项目制定未来数字金融世界的技术标准、建立法律权威,并将「新加坡牌照」打造成全球数字资产界的最高信誉标签。这一核心论点,为理解新加坡所有看似复杂的监管行为提供了统一的战略视角。

第二部分

新加坡的法律与司法生态系统

在第一部分阐明了新加坡「为何」要进行从「中心」到「枢纽」的宏大战略转型之后,我们现在将深入其监管的「发动机舱」,剖析其「如何」实现这一战略的法律与制度基石。这一切的核心,便是新加坡金融管理局(MAS)。

2.1 主要监管单位

在新加坡的金融监管版图中,新加坡金融管理局(MAS)承担中央银行与金融监管职能的核心角色,其监管覆盖面广且具有重要权威,但在具体事项上仍与司法机构、税务机关、数据保护监管机构(如 PDPC)等协同作用。MAS成立于1971年,其职能组合了银行、金融、财金等诸多机能。不同于许多国家的多头监管体系(例如,中国分业监管的「一元多头」体制),MAS拥有独一无二的集成化结构,集中央银行、综合金融监管和金融发展职能于一身。这一「三位一体」的独特设计,并非简单的职能叠加,而是新加坡高效、连贯且强大监管能力的根源。它形成了一个相互啮合、彼此加速的战略「飞轮」,使其能够在数字资产领域系统性地进行产业塑造和风险管控。

飞轮的初始推力,源于MAS最具新加坡特色的职能——金融发展促进者。MAS的目标是推动新加坡成为一个领先的国际金融中心,因此,它主动扮演着产业塑造者而非被动风险管理者的角色。正是这一发展职能,解释了为何MAS会通过金融部门技术与创新计划(FSTI)投入巨资(最新的FSTI 3.0计划甚至额外拨款S$1亿新元用于支持量子和AI领域),将新加坡金融科技节(SFF)打造成全球战略平台,并亲自下场主导「守护者计划」(Project Guardian),联合摩根大通、汇丰等行业巨头测试资产代币化。这些行动为整个系统注入了强大的创新动能。

然而,这一发展雄心,必然要求一个同样强大的监管框架来为其护航,这便启动了飞轮的第二个齿轮——MAS作为综合金融监管机构的角色。其监管范围的全面性(覆盖银行、保险、证券、支付等所有金融领域)带来了「无缝监管」的巨大优势,有效避免了对加密资产的「监管真空」。一个数字资产项目,无论其技术如何新颖,都必然会落入MAS的管辖范围:如果其代币被用于支付,则受《支付服务法》(PSA)监管;如果其具备资本市场产品的属性(即RWA),则受《证券及期货法》(SFA)监管。这种确定性,为创新划定了清晰而坚固的河道,确保其能量不会泛滥成灾。并且,随着新加坡国会通过《金融机构(杂项修正案)法案》(FIMA),MAS在六大金融领域的调查和监管权力还在不断升级。

最终,所有这一切发展与监管的行动,都必须服务于飞轮的最终锚点与制动器——MAS作为中央银行的核心使命。MAS负责维护新加坡元(SGD)的稳定、管理国家外汇储备,并促进非通货膨胀的经济增长。正是这一最终使命,使其对可能冲击货币体系的加密货币投机活动保持着高度警惕,并指导其战略性地「扬机构创新,抑零售投机」。这种警惕也体现在其对稳定币的严苛监管上:对于单一货币稳定币(SCS),MAS提出了极高的储备和赎回要求,包括其储备资产总价值不得低于流通总量的100%,必须在五个工作日内按面值赎回,且储备资产必须与发行方自有资产完全隔离托管。这一最终标尺,确保了整个飞轮的运转始终以国家金融稳定为最高依归。

宏大的战略飞轮并非空谈,它依靠一套高度专业化的内部齿轮来精准传动。创新项目首先敲开的是MAS的「创新前台」——金融科技与创新部门的大门,该部门负责推动FSTI计划和管理监管沙盒。一旦方向明确,项目便会被精准地导向两大核心引擎:负责PSA「防火墙」的支付部门,或是搭建SFA「未来之桥」的资本市场部门。而确保整个机器纪律严明、令行禁止的,则是MAS的「利齿」——执法部门,其权力随着FIMA法案的通过而得到显著加强。

新加坡金融管理局(MAS)在全球金融界是独一无二的。它是一个集战略制定、产业促进和严格执法于一体的单一权威。其「三位一体」的结构使其能够超越传统的监管角色,主动塑造数字金融的未来格局。MAS通过其发展职能制定前瞻性战略,通过其监管职能精准地划定合规边界,并通过其央行职能和强大的执法权力确保金融稳定和国际声誉。对MAS这一集成化、高效运转的「监管机器」的深刻理解,是所有市场参与者在新加坡数字资产生态中实现长期、可持续发展的核心前提。

2.2 防火墙与未来之桥

新加坡数字资产监管的坚实地基,依托于《支付服务法》(PSA)与《证券及期货法》(SFA)这两大支柱,以及其精心构建的一套「攻守兼备」的二元法律结构。

PSA的功能,是构筑一道坚不可摧的「防火墙」,通过对数字支付代币(DPT)及其服务商的严格监管,将零售加密货币活动中风险最高的环节——主要是反洗钱和反恐怖主义融资(AML/CFT)——隔离在严密的合规体系之内。

而SFA的使命,则是搭建一座通往制度化未来的「桥梁」,为机构级的、以真实世界资产(RWA)代币化为代表的下一代金融创新,提供一个确定、合规且与传统金融世界无缝衔接的法律轨道。正是这种分工明确、协同有力的战略工程,使得新加坡能够在坚守金融系统诚信的同时,大胆引领机构创新。

《支付服务法》(PSA)的战略深度

于2020年1月生效的《支付服务法》(PSA),是新加坡防御性战略的核心。在DPT看似平淡的法律定义背后,隐藏着MAS「手术刀式」的监管智慧。

其将DPT定义为一种意图作为交换媒介、但价值并非与任何法定货币挂钩的数字表示。这一精准的界定,使其能够明确地将比特币、以太币等主流加密货币纳入监管,同时又巧妙地将那些功能极其有限(如仅用于特定平台或游戏内部的功能性代币或积分)的平台内部代币可能排除在外,避免了「一刀切」式地扼杀所有创新。这也是MAS将监管火力集中于具有高风险属性的支付活动,而非代币的技术形式或功能集合的监管哲学的准确体现,为低风险、功能受限的代币留下了创新的空间。

PSA的监管网络覆盖之广,体现在其对七类核心支付活动的全面定义上。

七类受监管的支付服务包括:

账户发行服务(Account issuance service)

国内汇款服务(Domestic money transfer service)

跨境汇款服务(Cross-border money transfer service)

商户收单服务(Merchant acquisition service)

电子货币发行服务(E-money issuance service)

数字支付代币服务(Digital payment token service, DPT Service)

货币兑换服务(Money exchange service)

它不仅囊括了账户发行、境内外汇款等传统支付的基石,更精准地将矛头指向了加密经济的心脏——数字支付代币(DPT)服务本身。这意味着,无论是交易所、钱包服务商还是 OTC 平台,其核心业务——买卖、转账或托管 DPT ——都无可避免地落入这张法网之中。并且,这张法网还在不断加固:2021年的 PSA 修正案将 DPT 托管与传输服务明确纳入监管;而《金融服务与市场法案》(FSMA)引入的 DTSP 牌照,更是彻底填补了跨境监管的漏洞,将监管套利的空间压缩至极限。

这套牌照体系的精妙之处,在于其刻意制造的门槛梯度,它如同一部高效的「筛选器」,主动塑造着市场结构。

PSA 框架下有三种牌照:货币兑换商牌照、标准支付机构牌照(SPI)和主要支付机构牌照(MPI)。其中,SPI 和 MPI 是数字支付代币服务提供商(DTSP)的主要牌照类别。对于交易规模尚小的标准支付机构(SPI),监管仅设定了10万新元的基础资本门槛。然而,一旦业务规模触及每月300万新元的阈值,通往主要支付机构(MPI)的道路便陡然变窄,监管的强度也随之发生质变,资本金要求跃升至25万新元。但这仅仅是入场券。更重要的是, MPI 被强制要求遵循一套与主流金融机构看齐的严苛规定:从《技术风险管理指南》(TRM)的硬性指标,到客户资产的法定信托隔离,再到重大事件的快速上报机制。

这每一项规定,都在清晰地向市场宣告MAS的偏好:它所寻找的,是具备雄厚资本实力、完善风控体系和「机构基因」的长期玩家。也清晰地向市场传递了信号:新加坡欢迎负责任、有能力履行监管义务的机构,而不是仅仅追求短期利润的投机者。

因此,PSA 的战略意义远超满足FATF的AML/CFT要求。它通过严格的客户尽职调查(如 MAS PSN 02 号通知)和对「旅行规则」的遵循,为新加坡构筑了一道隔离洗钱与恐怖主义融资风险的「防火墙」。正是这座防火墙的有效运作,捍卫了新加坡作为顶级国际金融中心的AAA级声誉,而这种高度的公信力,正是其发展机构级应用的信任基石。

并且,MAS 将这些活动划分得如此细致,体现了监管的模块化设计。这种设计使得监管可以灵活地演进,例如《金融服务与市场法案》(FSMA)通过引入DTSP 牌照,进一步填补了 PSA 留下的跨境监管漏洞,将那些在新加坡注册但只服务海外客户的实体也纳入监管,从而堵住了监管套利空间。这种精确划分和集成,为其未来按需调整监管边界预留了清晰的「接口」。

《证券及期货法》(SFA)的战略远见

然而,捍卫城墙只是战略的一半,另一半则在于主动出击,搭建通往未来的桥梁。当一个数字代币的经济实质超越支付工具,具备投资属性时,其监管的接力棒便交给了《证券及期货法》(SFA)。

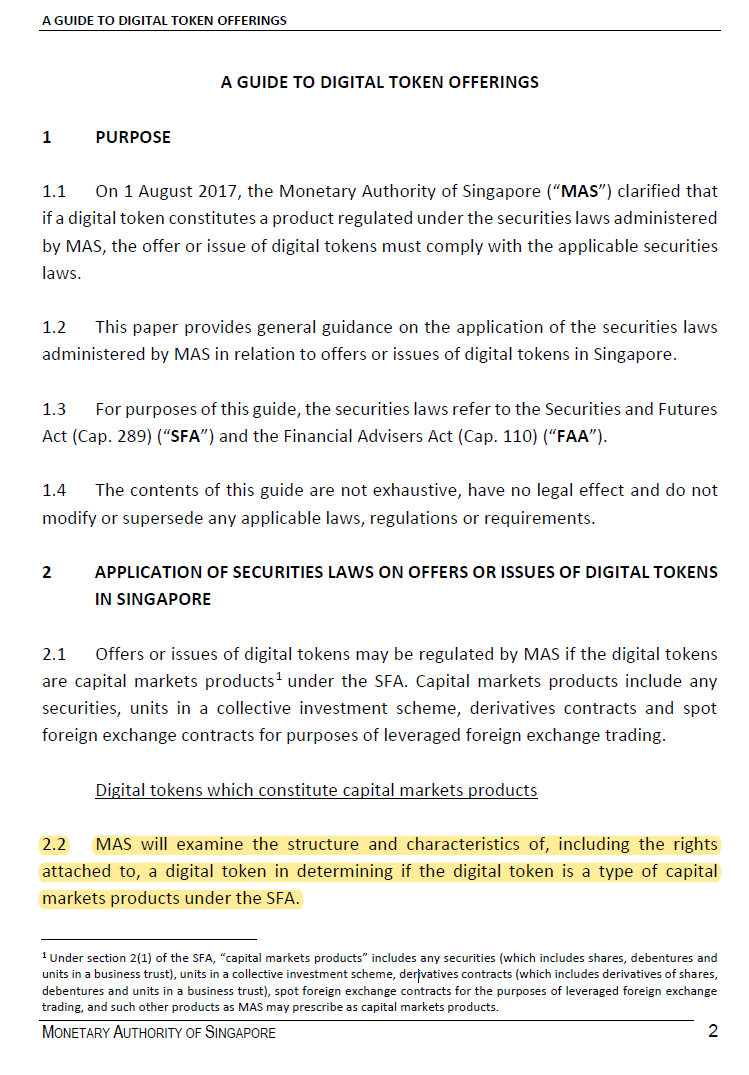

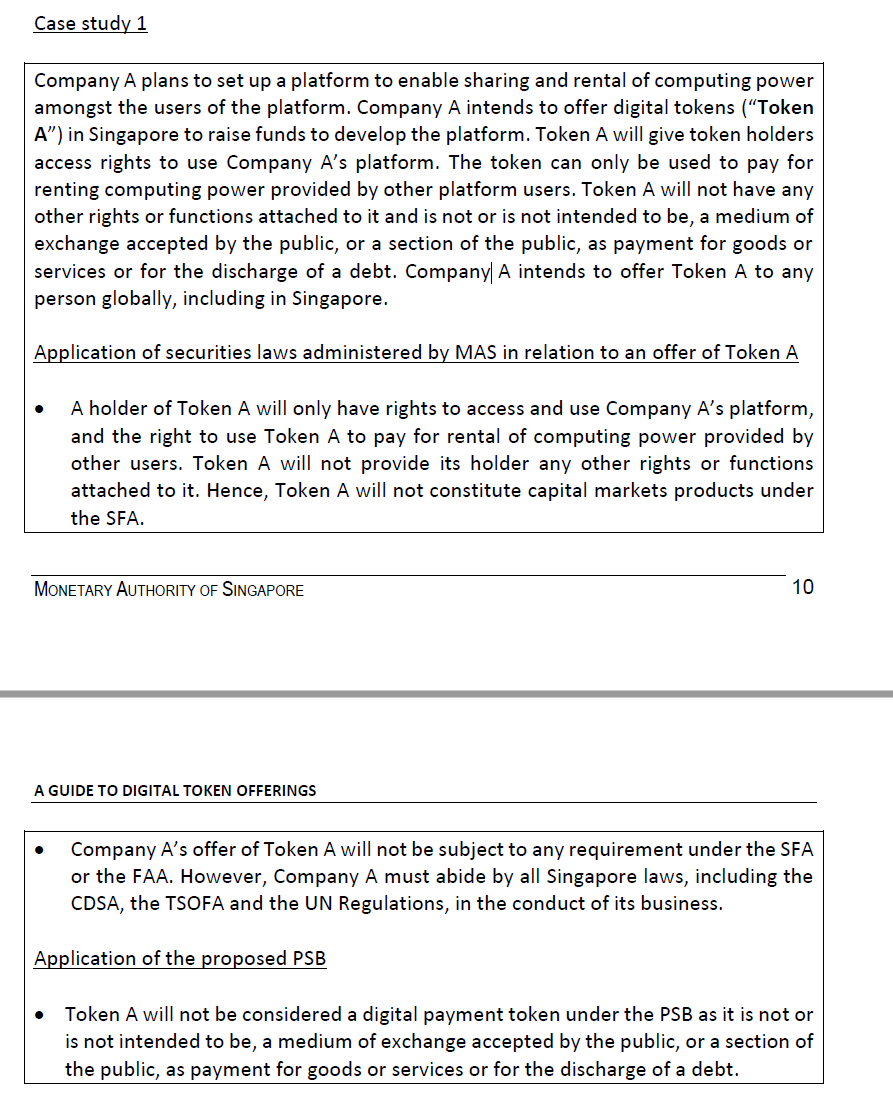

MAS如何判断一个代币的「灵魂」——即它究竟是支付工具还是投资合约——依靠的并非技术标签,而是一套基于「经济实质」的穿透式分析方法,其权威指南便是《数字代币发行指南》。

如果一个代币赋予持有者所有权、债权、利润分配权或类似的经济权益(例如,代表了某种股份或分红权益、集资投资计划的份额),那么无论其外在形式如何,它都将被认定为SFA下的「资本市场产品」。

这种基于个案分析的灵活性,使得MAS能够将任何通过技术伪装的证券型代币纳入监管,包括最前沿的RWA代币化产品。一旦被定性,其发行就必须遵循SFA关于招股说明书的严格要求,或通过面向机构及合格投资者的豁免路径进行合规发行。

SFA这部在「加密货币」概念出现之前就存在的法律,之所以能完美地成为监管RWA等前沿创新的基石,正是MAS「技术中立」原则威力的体现。

SFA监管的是金融活动本身,而非技术形式,这使其能够以不变应万变,为新一代金融产品提供成熟、确定且可靠的法律轨道——而这,正是机构投资者最渴求的。

RWA本质上是传统证券在区块链上的映射,SFA为其提供了无缝衔接的法律依据,避免了另立新法的漫长与不确定。MAS还正通过Project Guardian等项目,积极探索如何在SFA的框架下构建开放、可互操作的代币化网络,以此抢占下一代金融市场基础设施(FMI)的制高点。

攻守兼备的二元结构

PSA与SFA共同构成了新加坡数字资产监管体系的坚固地基,它们以高度协同的方式执行着国家战略。PSA建立起一道「防火墙」,通过严格的AML/CFT和TRM标准,将高风险的零售加密活动隔离在安全边界之内,维护了新加坡的金融公信力。SFA则搭建起一座「未来之桥」,为 RWA 和代币化证券等机构级高附加值创新提供了确定且合规的法律轨道。

这两者之间,存在着深刻的因果关系。PSA的强劲执行(特别是 FSMA 堵住跨境套利漏洞),是SFA能够成功的必要前提。只有在展示出捍卫金融系统纯洁性、毫不妥协地执行反洗钱规则的能力之后,新加坡才能赢得全球最保守、最审慎的机构资本的信任。只有当「防火墙」坚不可摧时,机构投资者才敢于、并愿意踏上这座通往未来的「桥梁」。

2.3 两法如何互动?

在清晰地剖析了新加坡的两大法律支柱后,真正的挑战浮出水面:在现实世界中,这两条泾渭分明的法律轨道,往往会在那些兼具多种属性的「混合型代币」(Hybrid Token)的模糊地带交汇。识别并应对这种交织,是项目在新加坡合规成功的关键。

这要求我们超越对法条的静态理解,掌握MAS「技术中立」与「实质重于形式」的动态监管思维。为此,我们不妨进行一场思想实验。

让我们给一个足以考验监管智慧的复杂样本:

一款名为「生态系统治理与支付代币」(EGPT)的混合型代币。在其所属的DeFi平台内,EGPT被赋予了双重使命:其一,它具备支付功能,用户可用其支付平台服务费,并在生态内的商家处作为交换媒介使用;其二,它承载着治理与收益分享功能,持有者通过质押(Staking)不仅能参与平台治理投票,更能定期获取平台净交易费用的分红。

面对这样一个「雌雄同体」的数字资产,我们应如何判断其法律身份?

首先,让我们戴上PSA的「透镜」来审视。从这个视角看,EGPT被意图并实际用于支付,其核心功能之一是作为交换媒介,且其价值与任何法定货币脱钩。这使其无可辩驳地落入了PSA对数字支付代币(DPT)的定义范畴。进而,如果运营该代币的平台提供了买卖、托管或法币兑换等服务,那么该平台就必须申请PSA牌照(SPI或MPI),供 EGPT 代币的买卖或交易服务(DPT 服务)、托管服务(例如托管钱包)、法币与 EGPT 之间的兑换服务,或涉及跨境转账服务(例如客户通过法币购买 EGPT)。并接受其关于反洗钱和支付风险的严密监管。

不过,如果从SFA的视角出发,情况可能更加有趣。SFA 监管的焦点是代币的经济实质,穿透其支付外衣,审视其赋予持有者的经济权利的实质。MAS在其《数字代币发行指南》中明确指出,判断的核心在于代币所赋予的权利。

2.2 MAS will examine the structure and characteristics of, including the rights attached to, a digital token in determining if the digital token is a type of capital markets products under the SFA.

EGPT赋予了持有者分享平台未来收益的权利。根据SFA的指导原则,如果代币代表了对公司的股权、债权,或构成了集合投资计划(CIS)的单位,它就会被视为证券型代币(即 CMP)。

在此案例中,如果平台将用户的 EGPT 质押资金汇集起来,由平台(或其关联实体)管理和投资,目的是让代币持有者分享运营或投资收益,则 EGPT极有可能被认定为构成CIS的单位。

当两副「透镜」的观察结果叠加,一个结论浮出水面:EGPT将受到「双重监管」。

这对项目方来说并不好笑。这绝非一个简单的法律标签,它启动了一场成本与复杂度急剧攀升的合规风暴。

首先是牌照申请的「双重门槛」:项目方不仅需要为 DPT 服务申请PSA牌照用于监管其 DPT 服务(如钱包托管、加密货币兑换或交易服务)。如果业务交易额超过 S300万新元/月或总交易额超过 S600万新元/月,则需要申请MPI牌照;

还可能需要为证券型代币的交易申请资本市场服务(CMS)牌照用于监管其资本市场产品相关服务。如果平台提供涉及 EGPT 交易、提供相关投资建议或运营证券型代币交易平台,则需要持有相应的 资本市场服务(CMS)牌照,例如交易证券型代币(Dealing in Capital Markets Products)的 CMS 牌照,或运营认证市场运营者(RMO)牌照。

但这仅仅是开始,真正的挑战在于运营中永无止境的「双轨制」合规。项目方必须同时满足两套不同法律体系的要求:既要遵循PSA框架下关于客户尽职调查(CDD)、资产隔离和技术风险管理(TRM)的严苛规定,又要满足SFA框架下关于招股说明书、信息披露和投资者适当性评估的复杂义务。

在这巨大的合规压力之下,项目方必须在代币经济模型(Tokenomics)的设计之初就做出根本性的战略抉择,这正是这个案例的价值所在。

一条路径是剥离证券属性,例如,彻底取消分红或收益分享的权利,将代币的功能限定为纯粹的实用型代币(Utility Token),以避免触发SFA的管辖。MAS在《A Guide to Digital Token Offerings》便明确指出,代币若仅授予访问/使用权而不赋予经济回报(如所有权、分红或收益分配),被归为证券的风险较低;但是否构成资本市场产品仍需基于对代币经济实质的个案分析判定,建议以具体代币架构为准并取得法律意见。

另一条路径,则是坦然接受机构化道路,将代币的发行和交易严格限定于合格投资者与机构投资者,从而利用SFA的豁免条款,规避面向零售市场时最为繁重的合规义务。

因此,这个案例可以为所有市场参与者提炼出一套根本性的自我评估框架。在踏入新加坡市场前,必须拷问项目的两个核心:其一,是代币的「灵魂」——它的核心功能究竟是支付、投资,还是仅仅是访问权?它的价值支撑究竟源自市场波动,还是与发行方的未来利润牢固绑定?其二,是运营的「行为」——业务模式是否触及了PSA定义的支付服务红线?营销推广是否跨越了面向零售投资者的禁区?对这两个维度的清晰回答,将最终决定一个项目在新加坡的命运:是陷入「双重监管」的泥潭,还是找到一条通往合规的清晰路径,这完全取决于其自身的战略抉择。

2.4 构成合规拼图的法律矩阵

在新加坡,成功获得《支付服务法》(PSA)或《证券及期货法》(SFA)的牌照,仅仅意味着取得了进入赛场的资格。真正的考验,在于如何在由操作、数据、公司、税务乃至刑法等多维度法规构成的复杂「法律矩阵」中长期生存并发展。这个矩阵将高阶的监管原则「翻译」为日常的操作要求,并由严厉的个人和刑事责任来兜底,确保合规不再是「勾选框」游戏,而是企业运营的核心要素。

这场合规的考验始于企业运营的最前线。在这里,MAS通过发布具有法律约束力的通告(Notices)和作为监管基准的指南(Guidelines),将抽象的原则转化为具体的战斗手册。

在反洗钱(AML/CFT)的战壕里,合规官必须依据《MAS PSN02号通知:关于防止洗钱和打击恐怖主义融资——数字支付代币服务提供商》:

客户尽职调查(CDD)和强化尽职调查(EDD):MAS PSN02 号通知要求 DPT 服务提供商采用基于风险的方法(RBA),并实施严格的客户尽职调查(CDD)程序。例如,MAS Notices on AML/CFT 要求金融机构对现有客户执行适当的CDD措施,同时考虑到对重要性和风险的自我评估。此外,对于尚未建立业务关系的客户,如果交易金额超过S$5,000 新元,支付服务提供商必须执行规定的 CDD 措施。

交易监控与可疑交易报告(STR):MAS Notices要求金融机构制定并实施内部 AML/CFT 政策、程序和控制措施,这其中包括发现可疑交易和报告可疑交易的义务。机构必须建立基础设施,将可疑交易报告(STR)提交给新加坡警察部队商业事务部下的可疑交易报告办公室(STRO),并将副本送交 MAS 备案。根据《MAS PSN03号通知》,在发现任何可疑活动或欺诈事件后,如果此类活动或事件对其安全性、稳健性或声誉至关重要,则必须在不迟于五个工作日内向 MAS 提交报告。

资源投入:PSN02 等通知对交易监控、KYC 和数据记录的要求,意味着项目方必须在合规团队、技术系统(如 KYC/KYT 供应商的选择)以及内部审计流程上进行巨大的资源投入。对于 DPT 服务提供商,若在开展指定支付服务业务过程中,处理、接受或执行的支付交易中向任何收款人支付等于或超过S$20,000 新元的现金,则被禁止。

与此同时,在技术风险的堡垒中,首席技术官(CTO)和首席信息安全官(CISO)则必须依据《技术风险管理指南》(TRM Guidelines)和《网络卫生通知》。MAS 明确表示,虽然 TRM 指南不具有法律约束力,但它们将作为 MAS 评估金融机构风险的基准,这意味着技术架构的稳健性本身就是合规的核心要素之一。还意味着他们必须确保至少每12个月对面向互联网的系统进行一次渗透测试,并具备在发生重大安全事件后1小时内上报的能力。MAS 还发布了关于网络卫生的通知,该通知于 2020 年 8 月 6 日生效,旨在推动金融机构采取足够措施保护自己免受日益普遍的网络风险。这两份文件和许多通知,共同构成了合规的「日常战争」,将监管意志注入了日常的每一笔交易和每一行代码。

操作所产生和处理的海量数据,立即引发了合规矩阵中的第二层张力:数据的内在冲突。一方面,AML/CFT法规要求企业尽可能多地收集和保留客户数据以备核查;另一方面,新加坡的《个人数据保护法》(PDPA)则以「数据最小化」和「目的限制」为核心原则,对数据收集施加了严格约束。

这种天然的「拔河」迫使企业必须在满足监管审查与保护用户隐私的钢丝上行走,设计出精密的内部数据治理政策、访问控制和保留策略,任何失误都可能导致高达100万新元或年营业额10%的巨额罚款。

紧接着,合规的责任链条从数据中心和服务器机房,无情地向上穿透,直达权力的顶层——董事会。在新加坡,公司法与金融监管紧密联动,合规的责任最终会「压」在每一位董事和高管的肩上。MAS发布的「适当和合适性标准指南」[FSG-G01]明确要求对包括董事和 CEO 在内的关键人员进行评估,其中考量因素包括诚实、正直、声誉、能力、胜任力,更包括对新加坡实体的「时间投入」。

当一家公司因严重的 AML 违规被 MAS 处罚时(例如罚款、限制经营范围、吊销或不换发营业执照),其董事会成员在新加坡《公司法》下可能面临个人法律责任,甚至在未经许可从事 DTSP 业务时,个人可能面临最高12.5万新元的罚款和长达三年的监禁。这种将责任「刺穿公司面纱」的机制,使得合规从一个部门的职责,升华为个人的、不可推卸的法律风险,显著影响了全球项目创始人在新加坡设立实体的决策。它要求创始人必须任命具备「适当和合适性」的常驻本地的执行董事,并确保他们对公司的合规控制和风险管理体系有充分的了解和监督。

随后,税务的维度则将所有运营行为转化为具体的财务成本与义务。新加坡税务局(IRAS)对数字资产的税务处理指南,要求企业根据其代币的性质和用途(例如是作为交易库存还是投资持有)来确定其税务责任。对从事 DPT 买卖或交易服务的公司,其持有的 DPT 通常被视为交易库存,相关的利润则应被视为应税收入。

而无论是 Staking 收益(质押收益)和 Airdrop(空投),IRAS 需要根据具体情况确定其是否构成应税收入,其复杂的税务定性都要求企业在商业模式设计之初就必须前置考虑其财务影响,并按时申报商品与服务税(GST)和所得税。

最后,在整个合规矩阵的基石部分,是不可逾越的刑法底线,由《贪污、贩毒和严重罪行法》(CDSA)构成。这并非日常操作指南,而是整个监管体系的最终「牙齿」。当一家持牌机构的合规疏漏严重到被认定为「洗钱」的上游犯罪时,CDSA 便会介入,将一个原本可能只是行政处罚的事件,升级为可能涉及监禁的刑事案件。

2023年曝光的、涉案金额高达30亿新元的「福建帮」跨境洗钱案,正是触碰了这条刑法红线,并直接催化了 MAS 对 DTSP 监管的紧急收紧。它以最冷酷的现实,展示了这条底线的绝对威慑力。

综上所述,新加坡的合规体系并非一张平面的法律清单,而是一个立体的、相互锁定的法律矩阵。它以PSA与SFA为轴心,确定了企业的法律身份;以MAS的各类通告与指南(如PSN02, TRM)为操作层,将监管意志注入日常的每一笔交易和每一行代码;再以《个人数据保护法》与《公司法》为侧翼,从数据治理和董事个人责任两个维度施加约束;最终,以《贪污、贩毒和严重罪行法》(CDSA)为坚不可摧的基石,设定了不可逾越的刑事红线。对任何意图在此长期发展的企业而言,看懂这张图谱,并将其内化为企业自身的DNA,不是一种选择,而是唯一的生存之道。

2.5 超越立法的「定心丸」

在全球数字资产的「法律蛮荒时代」,资本最大的恐惧,源于规则的缺位与争议的无解。成文法典固然重要,但真正让全球顶级机构资本敢于下重注的,是一个国家在争议发生后,提供确定性、终局性、且可被全球执行的司法救济的能力。

这,正是新加坡超越所有竞争者的王牌,是其给予全球资本的「定心丸」。在数字资产这个充满跨境性、技术复杂性和资产定性不确定性的前沿行业,新加坡国际商业法庭(SICC)和新加坡国际仲裁中心(SIAC)的存在,为这个混沌的世界提供了相当宝贵的资产。

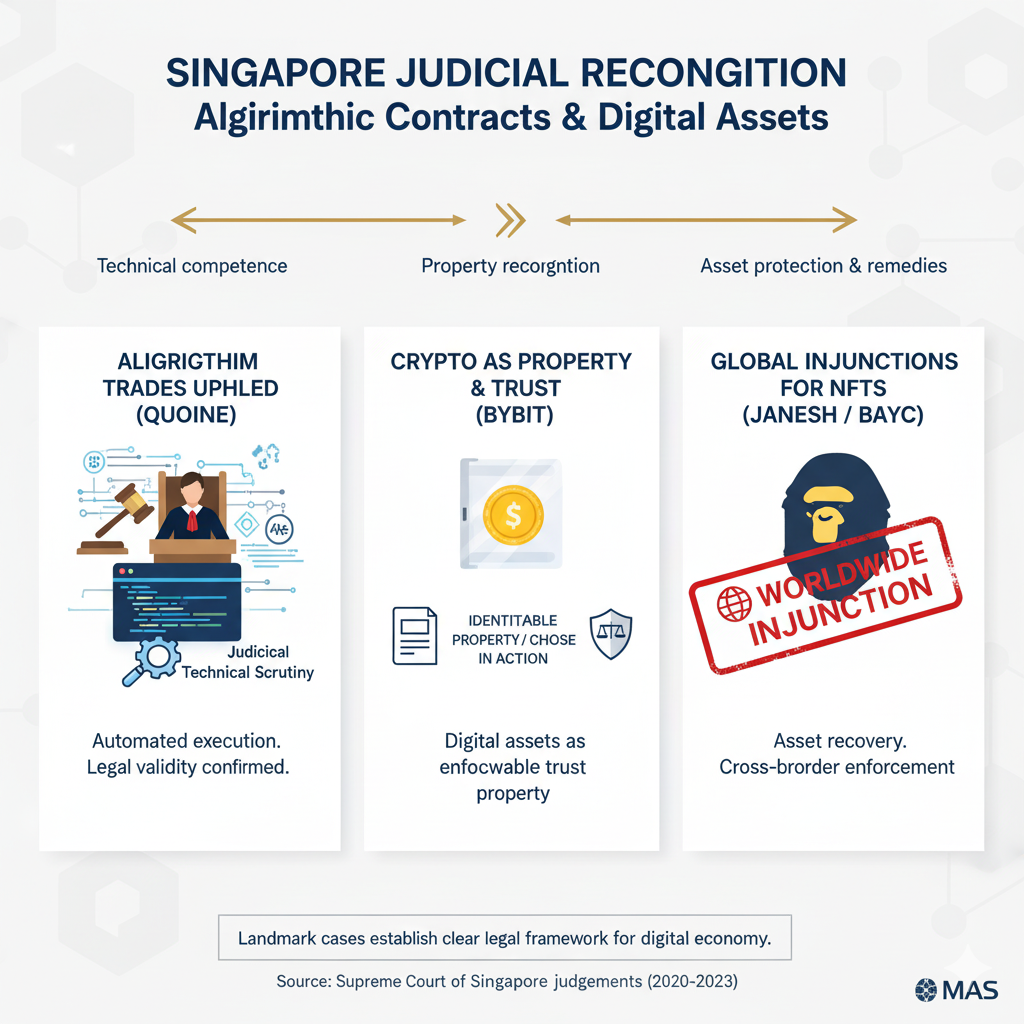

而论到资产,第一项便是弥足珍贵的,对「技术恐惧」的征服。当一笔因算法故障而产生的、价格畸高250倍的交易被加密货币交易所Quoine单方面撤销时,整个自动化交易世界都在观望。在「B2C2 Ltd v QuoinePteLtd SGHC(I) 03」一案中,新加坡国际商业法庭(SICC)的选择,不是回避技术的复杂性,而是迎难而上,深入剖析了算法交易的内部逻辑,最终肯定了在没有合同错误证据的情况下,通过算法执行的交易仍然具有法律约束力。

这一判决如同定海神针,为所有基于代码的商业约定注入了合同确定性,它清晰地向市场宣告:在新加坡,代码和算法所达成的商业约定,将受到普通法的有效保护。

这背后,是SICC及新加坡司法体系深刻的技术专长与商业实用主义。SICC 庭长菲立·惹耶勒南(Philip Jeyaretnam)指出,区块链、人工智能(AI)、加密货币等新兴技术带来了新的法律议题,未来的法官必须持续学习以适应新技术的挑战。他们愿意并有能力理解自动化交易系统、智能合约 和 DeFi 协议的内部逻辑,而非简单以「代码就是法律」或「技术黑盒」为由拒绝裁决。

紧接着,新加坡的司法体系又解决了行业的另一个根本性焦虑:我所持有的数字代币,在法律上究竟算不算「财产」?在「ByBit FintechLtdv Ho Kai Xin SGHC 199」一案中,法院做出了具有「立法性」意义的司法宣告,清晰地、毫不含糊地裁定加密资产(包括稳定币USDT)是一种可被识别和隔离的财产形式,能够被持有在信托之中。法院甚至援引了MAS 提议的关于数字支付代币隔离和托管要求的修正案,认为这些修正案反映了数字资产可以被识别和隔离的可能性,支持了它们可以被信托持有的观点。法院进一步裁定加密资产是一种诉讼权利(Chose in Action)。

这一裁决是具有里程碑意义的,它明确了加密资产在法律上属于财产,从而使数字资产所有者能够获得更强有力的保护,例如申请禁令(injunctions)以防止资产被盗用或转移。

原则被迅速延伸至新兴领域,在「Janesh s/o Rajkumar v Unknown Person (「CHEFPIERRE」)」案中,法院果断发出了全球财产禁令,以阻止一个无聊猿NFT(BAYC No 2162)的潜在出售和所有权转移。这一系列判决,为数字资产所有权的保护和被盗资产的追索,提供了坚不可摧的法律基石,为这颗「定心丸」增添了至关重要的成分。

然而,所有这些裁决,如果无法在现实世界中兑现,便毫无意义。这引出了最后一个,也是最关键的问题:在新加坡获得的判决,在海外有用吗?至此,新加坡的终极武器才完全展露。SIAC作为全球领先的仲裁机构,其裁决基于《纽约公约》可在全球160多个国家和地区获得承认与执行。而SICC则凭借其由来自全球主要法系的24名国际法官组成的豪华阵容,确保了其判决能够深刻理解并处理复杂的跨国界、跨法系纠纷,从而具备广泛的国际承认度。这赋予了新加坡的司法救济一种无可匹敌的全球力量——它提供的不仅是法律上的胜利,更是现实世界中可以兑现的权力。

至此,新加坡模式的全貌清晰地展现在我们面前。它的成功,源于一套完美的「双重保障」体系。一方面,是以PSA、SFA及其法律矩阵构筑的、坚不可摧的「事前监管防火墙」,它负责筛选参与者,防范于未然。另一方面,是以SICC和SIAC为代表的、无可匹敌的「事后救济定心丸」,它负责在混乱发生时,提供秩序与终局。

正是这套「立法+司法」的双重保障,为全球机构资本提供了一个完整的、从准入到退出(争议解决)的全周期法律安全感,共同铸就了新加坡作为全球「机构创新与治理枢纽」的独一无二、难以复制的核心竞争力。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。