作者:赵启睿

编审:赵一丹

在上篇《数字资产财库(DAT)新型企业范式的战略分析(上)》,我们回答了「过去」,以及「现在」的问题。

我们从经济层面回答了 DAT 作为一种资产配置手段,在当前环境下的偶然以及必然。同时,接着回答了目前的企业配置DAT现状发生的分野以及意义。

在这篇,我们将继续回答 DAT 本质上的一些优势以及潜力,旨在给人们以更加深刻的视野。

第三部分:一种新资产物种的诞生

对于企业财务官而言,资本配置的工具箱一向是清晰而成熟的。

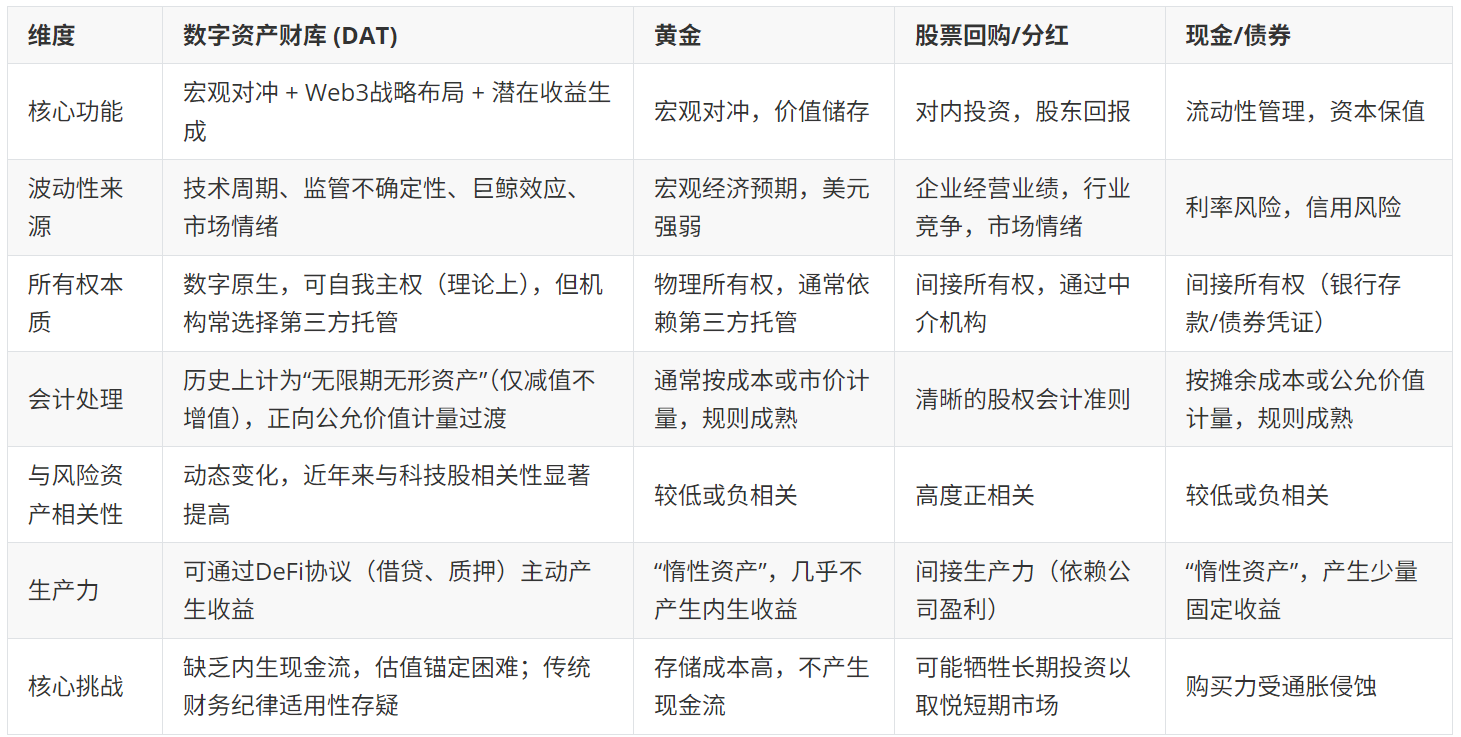

无论是用于管理流动性的现金与债券,用于回馈股东的股票回购,还是用于对冲宏观风险的黄金,每一种工具都有着经过数十年市场检验的成熟逻辑。然而,数字资产财库(DAT)的出现,并非仅仅是在这个工具箱中增加了一个新选项;它引入的是一种全新的资产「物种」,其底层逻辑与所有传统工具都存在根本性差异。

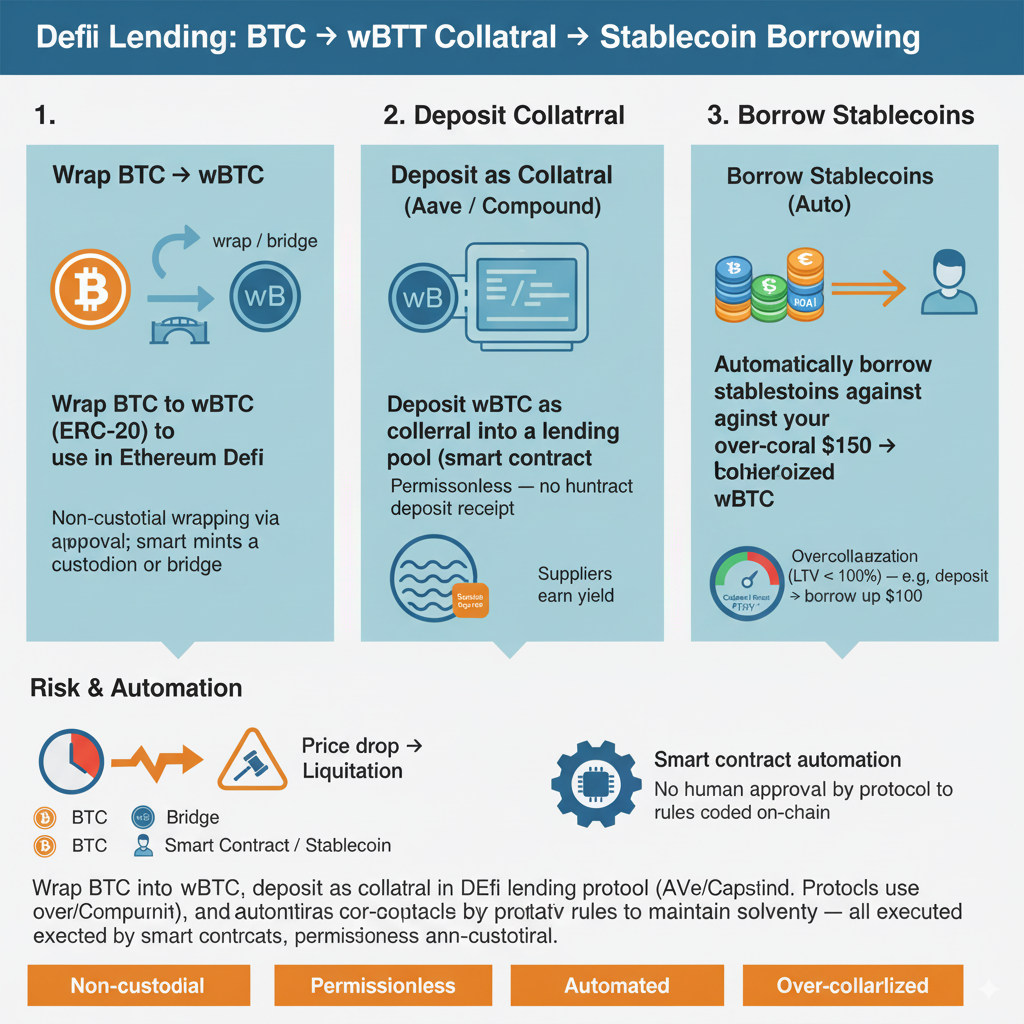

这种差异首先体现在其前所未有的「可编程生产力」上。传统财库中的核心资产,如现金和黄金,本质上是「惰性」的,其自身几乎不产生任何收益。而 DAT 资产,特别是构建在智能合约平台上的资产,具备前所未有的「活性」。通过去中心化金融(DeFi)协议,公司理论上可以将其持有的数字资产(如将BTC封装为wBTC)投入借贷市场(如Aave、Compound)赚取利息,或参与流动性挖矿和质押(Staking),从而将其财库资产从一个被动的价值储存工具转变为一个主动的收益生成引擎。这种潜力是革命性的,但其代价是引入了全新的风险维度——智能合约的漏洞、预言机的操纵以及协议的治理风险,这些都是传统金融风险模型难以覆盖的领域。

如果说可编程性是其「动态」基因,那么其「静态」基因——可自持的主权所有权——则更加颠覆。对传统股票和债券的所有权,本质上是间接的,依赖于一长串中介机构(券商、托管行、中央存管机构如DTCC)的信用背书。黄金的实物所有权虽然直接,但出于安全和流动性的考虑,机构通常会将其托管在专业的金库中,同样依赖第三方。而数字资产作为一种可自我主权的数字原生承载资产(Bearer Asset),其所有权由私钥直接证明,理论上无需任何中介即可在全球范围内转移,赋予了企业前所未有的资产控制力。然而,这也催生了一个深刻的「主权的悖论」:在实践中,上市公司出于合规、安全和操作便利性的考量,往往选择将资产托管给如 Coinbase、BitGo 或 Fidelity Digital Assets 等第三方专业机构。这一决策虽降低了操作风险,却也削弱了「自我主权」的核心优势,重新引入了在 FTX 和 Celsius 等平台破产案中暴露无遗的对手方风险和托管风险,在「完全主权」与「合规便利」之间形成了一种艰难的权衡。

一个具有如此颠覆性基因的「新物种」,被引入到一个为传统资产设计的「旧生态系统」中时,必然会引发一系列剧烈的「系统性排异反应」。

首先体现在其剧烈的波动性与不稳定的市场联动性上。DAT 的波动性来源远比传统资产复杂,它由技术周期、监管突变、以及高度集中的「巨鲸效应」共同驱动,这是传统风险模型难以捕捉的。更重要的是,随着机构投资者的涌入,比特币作为独立「数字黄金」的叙事正在被削弱,其与纳斯达克等科技股指数的相关性显著提高。这引发了一个核心问题:DAT 究竟是真正的风险分散工具,还是仅仅是传统风险资产的一个高贝塔(高波动性)版本?答案似乎是后者,这意味着在系统性风险爆发时,DAT 可能无法提供预期的对冲保护,反而可能放大损失。

这种排异反应,在会计与监管的语言冲突中表现得尤为深刻。在美国通用会计准则(U.S. GAAP)下,直到近期修订前,数字资产一直被归类为「无限期无形资产」。这种分类导致了一种不对称的会计处理:当资产价格下跌时,公司必须计提减值损失,直接冲击利润表;而当价格回升时,却不能确认未实现的收益,账面价值可能远低于市场价值。这种「只报忧不报喜」的规则,导致公司财报严重扭曲,无法公允地反映其数字资产的真实经济价值,给 CFO 与资本市场的沟通带来了巨大障碍。尽管美国财务会计准则委员会(FASB)已发布新规(ASU 2023-08)允许采用公允价值计量,但这一转变的全面实施仍需时间,且全球范围内的会计准则尚未统一。

这本质上是旧世界的会计语言,在试图描述一个新物种时发生的系统性失灵。

合成对比表格:DAT vs. 传统资产配置

综上所述,DAT 并非传统资产的简单延伸。它的核心特性——可编程的生产力与可自持的主权——决定了它是一种全新的战略资产。而我们所观察到的极端波动、会计扭曲与监管冲突,并非其孤立的缺陷,而是这一新物种的颠覆性基因与传统金融生态系统发生碰撞时,所产生的必然结果。对于决策者而言,这不仅意味着接纳一种新资产,更意味着要准备好应对一种全新的、充满不确定性的财务与治理逻辑。

第四部分:DAT的赋能潜力

4.1 从成本中心到利润中心

传统的企业财资管理部门,其核心使命长期以来被定义为一种防御性姿态:确保流动性、管理现金流、控制汇率风险,并以最低风险保存资本。在这一框架下,财资部本质上是一个成本中心——其成功与否,衡量标准是风险规避和成本控制的效率,而非价值创造的能力。

因此,如前文所述,在后疫情时代的宏观经济背景下,企业财资官(CFO)面临着一个前所未有的双重困境:一方面,持续的量化宽松政策正系统性地稀释现金储备的购买力;另一方面,长期低利率环境使得政府债券等传统避险资产的保值功能几乎完全失效。正是在这一传统工具箱集体失灵的背景下,数字资产财库(DAT)作为一种激进的解决方案,进入了决策者的视野,它蕴含着将财资部从一个被动的成本中心,重塑为一个主动的、高风险高回报的利润中心的颠覆性潜力。

这一潜力的「进攻」维度,在 Strategy 公司(原 MicroStrategy)的案例中得到了最极致的展现。其战略的核心,是将源于「防御」的动机——对抗法定货币贬值——通过极具「进攻性」的金融工程来实现。通过发行低息可转换债券和增发股票等工具,公司不仅将其资产负债表与比特币深度绑定,更在资本市场上创造了一个强大的「金融飞轮」。

2020 年 8 月,当 MicroStrategy 首次宣布将购买价值 2.5 亿美元的比特币作为其主要储备资产时,在当时及随后数年,由于美国证券交易委员会(SEC)尚未批准现货比特币ETF,寻求合规、便捷比特币敞口的机构和散户投资者渠道极为有限。MicroStrategy的股票恰好填补了这一市场空白,迅速被投资者视为一种「事实上的、带杠杆的比特币投资工具」,有效地扮演了「事实上的代理ETF」角色:

估值模型脱钩:MicroStrategy 的股价不再与其主营的商业智能软件业务的市盈率(P/E)或市销率(P/S)挂钩,而是与其资产负债表上持有的比特币净资产价值(Net Asset Value, NAV)高度绑定。

杠杆效应放大:公司通过发行低息可转换债券和增发股票等金融工具,持续为购买比特币融资。这种主动的、杠杆化的增持策略,使其股价波动性甚至超过了比特币本身,吸引了大量寻求高风险回报的投资者和期权交易者。

资本飞轮效应:股价相对于 NAV 的溢价(mNAV > 1)形成了一个自我强化的「金融飞轮」。公司可以利用被市场高估的股票来筹集资金,购入更多比特币,从而提升每股含币量(BPS),进一步强化其「比特币代理股」的叙事,维持甚至推高溢价。

然而,这种财务上的巨大成功,也立即引发了一个深刻的治理质问,即所谓的「代理陷阱」:当一家公司的主营软件业务(来自美国证券交易委员会 mstr-10k:2021–2023 年业务收入约 5 亿美元)在其数百亿美元的比特币储备面前显得微不足道,其股价几乎完全由单一资产的价格波动主导时,它究竟还是一家科技公司,还是已经异化为一个高风险、几乎投资单一资产且缺乏监管的信托基金?公司命运与一种高波动性资产深度绑定,这种做法究竟是对股东价值的终极赋能,还是将公司置于一场无法回头的巨大赌局之中?

这种财务赋能的潜力并非个例。我们可以进行一个思想实验:

- 根据美国劳工统计局(Bureau of Labor Statistics)的数据,美国消费者物价指数(CPI-U)从2020 年 1 月的 257.971 上涨至 2021 年 12 月的 280.126。

- 两年间的累计通货膨胀率为 8.59%((280.126 / 257.971) - 1)。

- 因此,剩余 9.9 亿美元现金的实际购买力损失约为 8504 万美元($990,000,000 * 8.59%)

然而,就在这个看似完美的对冲故事背后,潜藏着两个悖论。

第一个是「对冲的悖论」。一种合格的对冲工具,其首要目标应是降低投资组合的整体风险。而比特币高达 75% 甚至更高的年化波动率,远超其试图对冲的通胀率。这种用一场「风暴」去对冲一场「小雨」的做法,是否从根本上增加了公司的整体财务风险?理性的决策者必须超越简单的回报计算,采用更复杂的「风险贡献度」(Contribution to Risk)分析框架,来量化 DAT 在不同市场环境下,究竟是风险的分散器,还是风险的放大器。

第二个,也是更具现实困境的,是「会计的噩梦」。即便 CFO 在思想上接受了这种波动性风险,在实践中也必须面对美国通用会计准则(U.S. GAAP)的扭曲效应。直到近期修订前,比特币被归类为「无限期无形资产」。这意味着,会计准则要求企业在比特币价格下跌时必须计提减值损失,但在价格回升时却不能确认未实现的收益。这种不对称的处理方式,会使上述思想实验中的美好故事,在季度财报上呈现为剧烈的盈利波动和潜在的巨额亏损。这使得任何 CFO 在做出这一配置决策时,都必须回答一个直击其受托责任核心的问题:在没有预知未来的前提下,这一决策究竟是「有远见的战略」,还是纯粹的「风险」?

归根结底,DAT 在财务层面的赋能,并非简单的资产增值,而是一次对企业财资管理哲学的根本性重塑。它引出了一个更深层次的反论:企业财资部的核心竞争力究竟是流动性与风险管理,还是二级市场的资产投机?将财资部推向利润中心的角色,是否会使企业偏离其主营业务的航道,并引入其自身不具备专业管理能力的全新风险?

这或许是所有考虑采纳 DAT 策略的董事会,都必须首先回答的问题。

4.2 从财务报表到战略宣言

如果说财务层面的赋能是 DAT 策略带来的即时「战术优势」,那么其真正深远且颠覆性的影响力则体现在战略层面。

采纳DAT策略,远不止是在资产负债表上增加一个新科目;它是一次深刻的身份重塑和未来路径选择,是将一份记录历史的财务文件,转变为一张宣告未来意图的战略宣言:它不仅在适应现在,更在主动拥抱和构建未来。

这一宣言首先是一面升向外部世界的「身份信号旗」,其核心功能是重塑品牌认知并争夺关键资源。对于一家传统公司而言,宣布将比特币等数字资产纳入财库,是一次极其高效的品牌叙事投资。

美图公司的案例便极具代表性,其在 2021 年的购币公告,成功地将其品牌形象从一个传统的互联网工具公司,转变为一个积极探索 Web3 的科技先锋,极大地提升了其在资本市场和年轻用户群体中的关注度。同样,这一信号也是一个独特的「人才磁铁」,向全球顶尖的 Web3 人才宣告,这里有他们可以探索的土壤。然而,这一战略的内在矛盾在于,信号本身具有「半衰期」。当越来越多的公司采取类似行动,这种信号的独特性和价值是否会迅速递减?更重要的是,在努力吸引新群体的同时,这种激进的「身份重塑」是否会疏远公司原有的核心客户与传统机构投资者,带来「捡了芝麻,丢了西瓜」的风险?这正是品牌重塑策略一体两面的内在挑战。

但一个信号,如果缺乏实质的支撑,会迅速沦为噪音。DAT 的真正战略深度,在于这一外部的「身份宣告」,如何转化为一种不可逆转的内部压力,迫使企业为避免沦为「口头巨人」,而去真实地构建进入未来去中心化经济所必需的组织能力。

一旦资产负债表上出现了比特币或以太坊,它便会倒逼整个组织进行一场痛苦但必要的自我革命,去建立一套全新的「组织肌肉记忆」。财务与法务部门被迫去学习全新的会计准则与监管路径;技术团队必须掌握私钥管理、多重签名钱包等核心技能,并建立机构级的安全体系;合规部门则需要对接全球反洗钱(AML)框架。这一过程的核心挣扎,在于企业究竟是在进行真正的组织进化,还是在进行一场「货物崇拜」(Cargo Cult)式的战略模仿。如果一家公司仅仅模仿「买币」的表面行为,而其组织能力、商业模式和战略规划并未随之演进,那么这种「创新剧场」式的策略,除了在牛市中带来账面浮盈外,无法转化为任何真实的、可持续的竞争优势。

真正的组织进化,体现在 Block 公司(原Square)与云锋金融的战略之中。Block 持有比特币的决策,与其 TBD 部门致力于构建去中心化网络(Web5)的长期愿景紧密相连,持有资产成为了其团队理解、构建和推广去中心化身份(DIDs)和数据存储(DWNs)的技术和哲学基础。同样,云锋金融购买以太坊,也是明确指出此举是为了支持其在 RWA 代币化和 Web3 场景的布局,同时探索与保险等核心业务的结合。持有ETH使其能够直接参与和理解以太坊生态,为其 RWA 战略提供了不可或缺的技术底座和实践经验。

最终,采纳 DAT 在战略层面的真正价值,正在于这个「内外双效」的动态循环之中:外部的信号吸引了资源与关注,而这些资源与关注又为内部的能力构建提供了动力与合法性;内部能力的增强,又进一步验证了外部信号的真实性,使其品牌重塑更为可信和持久。正是通过驾驭这一循环,企业才得以将一份静态的资产购买行为,转化为一种动态的、能够创造宝贵「战略选择权」(Strategic Optionality)的长期优势,使其在面对不确定的技术范式突变时,能够从被动的防御者转变为主动的出击者。

4.3 重塑企业的金融管道

数字资产财库(DAT)的颠覆性潜力不仅限于财务增值和战略定位,它同样深刻地渗透到企业运营的「毛细血管」之中,为重塑其核心的金融「管道」——即资金的流转、获取与重构——提供了一套强大的新工具。

长期以来,企业的全球运营始终受困于传统跨境支付体系的根本性效率瓶颈。以 SWIFT 网络为例,一笔 100 万美元的货款在代理行之间层层流转,不仅耗时数日,且成本高昂。DAT 则提供了一种近乎「无摩擦」的替代方案。由美元 1:1 锚定的稳定币(如 USDC),利用全天候运行的公共区块链作为全球统一结算层,能够将结算周期从数天压缩至分钟级,成本也从数千美元降至几美元的 Gas 费。

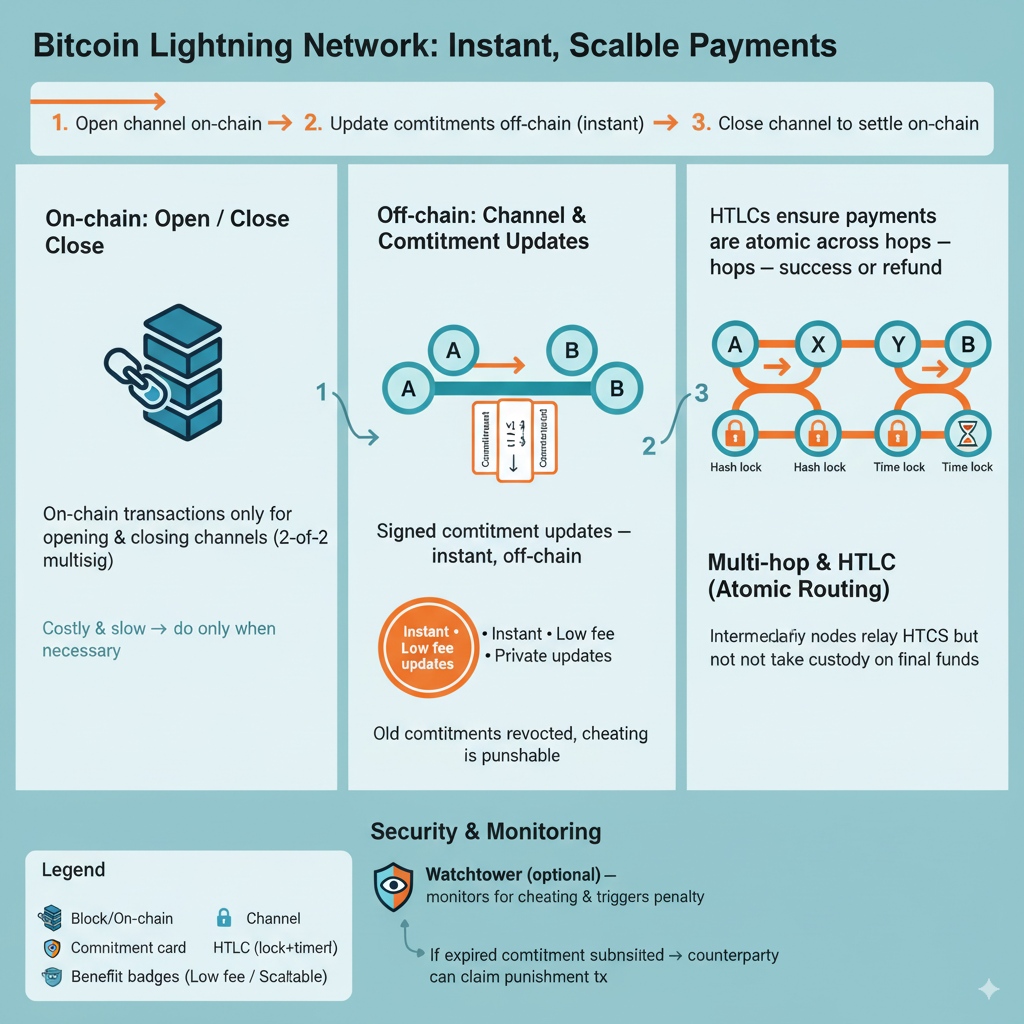

除去大额结算中的应用,比特币的第二层解决方案——闪电网络(Lightning Network)——在小额、高频的微支付场景下展现出巨大理论潜力。它旨在实现近乎零成本、瞬时完成的支付,为未来数字经济中的机器对机器(M2M)支付、内容付费等场景提供了技术想象空间。

然而,这幅美好图景在实践中必须面对支付的「最后一公里」难题:企业如何在合规、低成本的前提下,大规模地实现银行账户法币与链上稳定币之间的顺畅兑换?这一出入金(On/Off-Ramp)环节的摩擦,包括银行合作的限制、兑换平台的流动性成本以及潜在的合规审查的延迟,在很大程度上制约着稳定币结算方案的规模化落地。

这种在资金流转效率上的革命性提升,自然引出了下一个逻辑问题:企业能否以同样高效的方式获取资金?

DAT 通过将数字资产(如 BTC、ETH)定义为一种新型的、全球通用的合格抵押品,开辟了全新的融资路径。企业既可以通过将其持有的数字资产抵押给如 Ledn 等中心化金融(CeFi)平台,快速获得法定货币贷款以满足短期周转需求;

也可以通过 Aave、Compound 等去中心化金融(DeFi)协议,以非托管、无需许可的方式自动借出稳定币。具体操作上,企业可将 BTC 封装为 wBTC,通过智能合约将其存入协议作为抵押品,然后无需任何人工审批或许可,即可自动借出稳定币。DeFi 协议通常采用「超额抵押」机制来管理风险,即借款金额远低于抵押品价值,从而保证系统的偿付能力。

但这两种路径,都伴随着深刻的、曾引发行业灾难的风险。CeFi 借贷的历史充满了 Celsius、BlockFi、Genesis 等平台的灾难性破产,企业在享受其便利性的同时,也必须直面那深不见底的「对手方风险」黑洞——一旦平台挪用客户资产或经营不善,企业抵押的资产可能血本无归。而在 DeFi 中,虽然消除了中心化的对手方,但企业又必须面对另一种同样致命的风险:智能合约的漏洞(如闪电贷攻击)。代码的不可篡改性意味着,一旦漏洞被利用,损失几乎是瞬时且无法挽回的。

一旦企业掌握了如何高效地流转和获取资金,其运营演进的终极形态,便是重构其与资本市场的接口本身。这便是现实世界资产代币化(RWA)所描绘的未来愿景。理论上,企业未来可以将自身的债券、股权甚至未来收入流在区块链上发行,转化为「证券型代币」。这种「链上融资」模式,具备移除昂贵中介、降低发行成本、打破地域限制、并实现资产「可分割性」的革命性潜力。

然而,这一宏大愿景的实现,目前仍隔着一道由合规与技术构成的巨大天堑。它与现行的证券法体系(特别是美国的 Howey 测试)存在着根本性的冲突:一个代币是否构成「投资合同」从而被认定为证券,至今仍是监管的灰色地带。同时,当前区块链技术的可扩展性与安全性,是否足以支撑一家主流企业的核心融资活动,也是一个悬而未决的问题。网络拥堵、高昂的交易费用以及智能合约的漏洞风险,都构成了巨大的技术天堑。这些看似触手可及的运营优化,距离大规模、安全、合规地落地,可能还隔着一道难以逾越的鸿沟。

综上所述,DAT 在运营层面的赋能是真实而深刻的。但它的演进路径并非用完美方案替代旧问题,而更像是一场在全新风险版图上的权衡与探索。

从支付结算的「最后一公里」,到 CeFi 借贷的「对手方黑洞」,再到链上融资的「合规天堑」,每一步效率的提升,都伴随着一个更复杂、更需要专业智慧去驾驭的新型风险。

至此,有关 DAT,我们已经说明了它的前世今生。在下篇,我们将回答 DAT 的法律技术合规雷点,以及发展的未来前景。

通过三篇文章一个系列,将近 40000 字的深度解析,我们相信,这将给读者们建立相当全面、深刻、辩证的系统性认识。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。