*Written by:Knower*, **Mosi

Compiled by: Yangz, Techub News

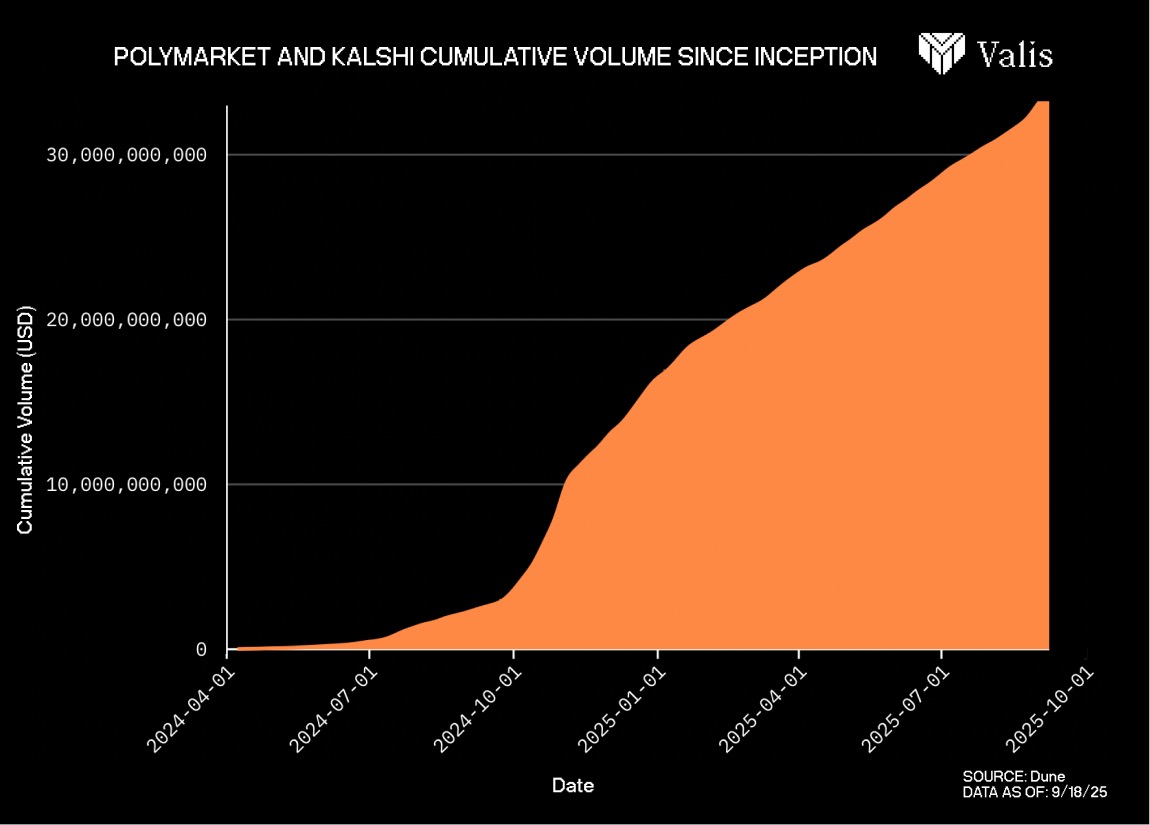

Prediction markets are everywhere. After the 2024 U.S. presidential election, it was predicted that the trading volume on Polymarket and Kalshi would plummet as it had in previous years. However, this did not happen, and our goal today is to analyze why they have maintained their significance and what we can expect if these trading volumes continue to gradually rise over the next 2-3 years.

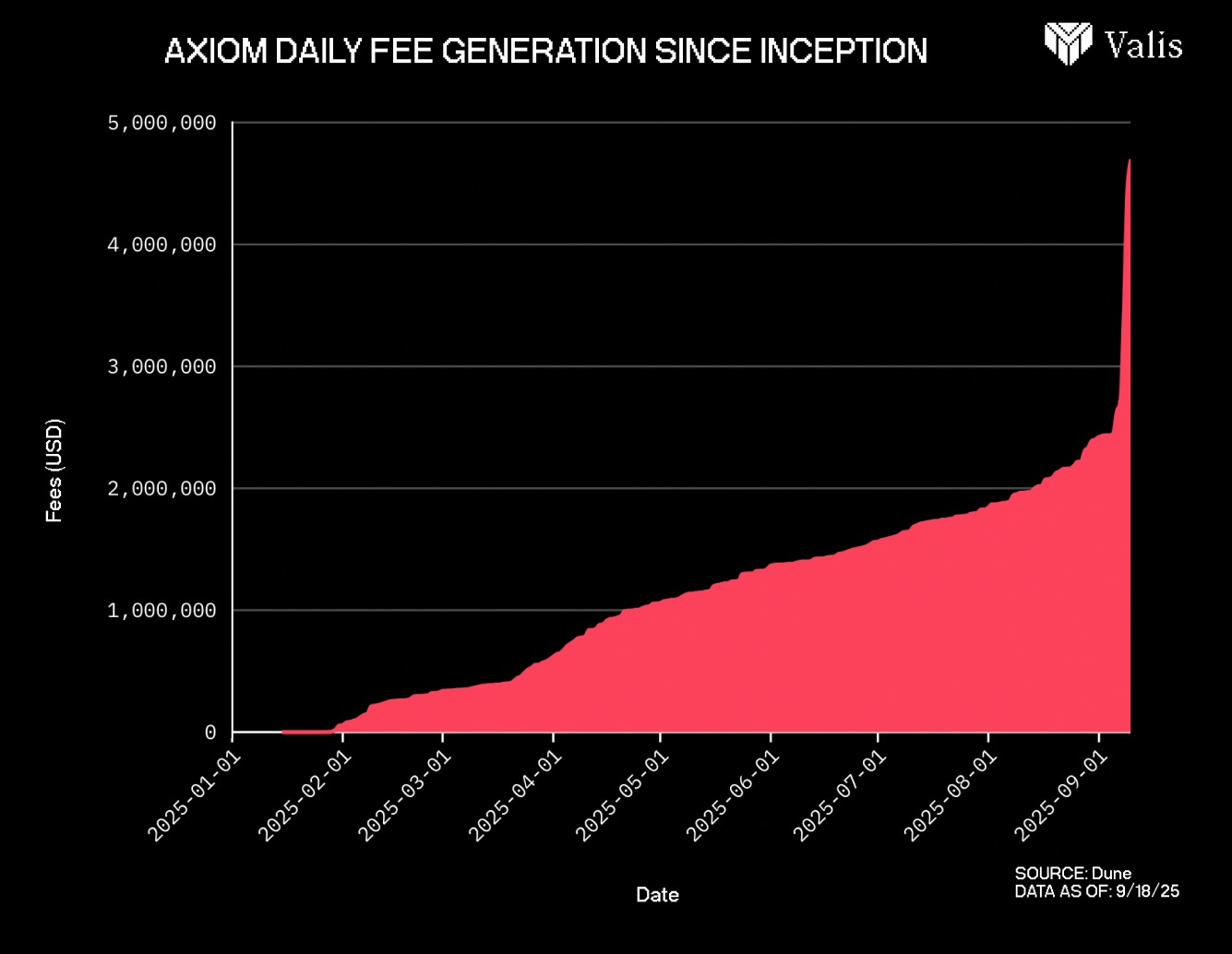

As a reference, according to Dune data, Kalshi and Polymarket have processed over $35 billion in trading volume since their inception, with a total trading volume of $17.5 billion from 2025 to date. It is evident that prediction markets are no longer a niche form of speculation for hobbyists or data geeks, but rather an option easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection, warranting deeper analysis. Moreover, this measurable success is just the beginning; some view it as merely a drop in the ocean compared to future potential.

As @semajieth stated, "Prediction markets have recently been described in various ways: as a financialization of collective intelligence, the most democratic financial market created to date, or simply the future of speculation."

In the past month, the X platform has been flooded with superficial content, providing lengthy analyses on anything you want to know about prediction markets and explaining how anyone can easily make money by trading on event outcomes.

However, rather than inundating you with trading ideas or filling your mind with wishful thinking, we will provide you with a comprehensive overview of the top prediction market platforms and how they have evolved to their current status, analyzing smaller but interesting areas such as market maker dynamics, trading volumes across markets, the distribution of open contracts, historical accuracy across multiple platforms, and many other foundational topics that will help you better understand.

At its most basic level, a prediction market is a financial tool that allows people to trade contracts linked to the outcomes of real-world events, winning when they are correct and losing when they are wrong. Of course, this is just a very superficial explanation, and you may be wondering how this differs from other types of investments or what its true innovation lies in.

People enjoy trading prediction market contracts not only because of the lucrative returns but also due to the vast array of tradable content. Before the advent of user-friendly prediction market interfaces, if you wanted to bet on an event, the only options were opaque over-the-counter trades or random internet trading counterparts. Today, reading a news headline, scoffing at a journalist's opinion, and then pulling out $100 to bet on an outcome completely opposite to what you just read has become easier than ever.

In the words of Camilo, "They distill the complexity of investing into a single equation of risk, return, and probability," which is a great way to express that prediction markets make previously difficult-to-execute trades (which required complex financial instruments) almost immediately accessible to the average user.

Robin Hanson is regarded by many as the "father of prediction markets," largely due to his extensive work on forecasting, idea futures, decision markets, and other related topics. Many of his writings can be found here. Although these insightful articles have existed for a long time (many trace back to the early 1990s), prediction markets at that time were limited to academia and a small circle of geeks, more like a castle in the air than a viable financial tool.

While it took years, some unexpected names laid the groundwork for Polymarket, Kalshi, and all the other companies today. Here are some notable experiments provided by Adjacent Research:

“Terrorism Futures” created by the Pentagon in 2005

Google ran its own internal prediction market

The CIA released a report analyzing the potential of prediction markets to enhance U.S. intelligence capabilities

Today, the success of prediction markets is not due to what they are, but rather to the functions they can perform, and of course, what they might mean for the global market structure.

What You Will Learn

Most of what you hear about prediction markets is correct, but no one has really tried to outline the key features that contribute to the sustained success of these platforms. This report will answer the following and more questions:

How do market makers and liquidity providers operate on Polymarket and Kalshi?

What are the reward/incentive structures of these exchanges?

How significant are concerns about market manipulation? What measures are being taken to mitigate this risk?

Which markets are more likely to receive higher incentive allocations?

Why have over-the-counter betting or leveraged trading not received more attention?

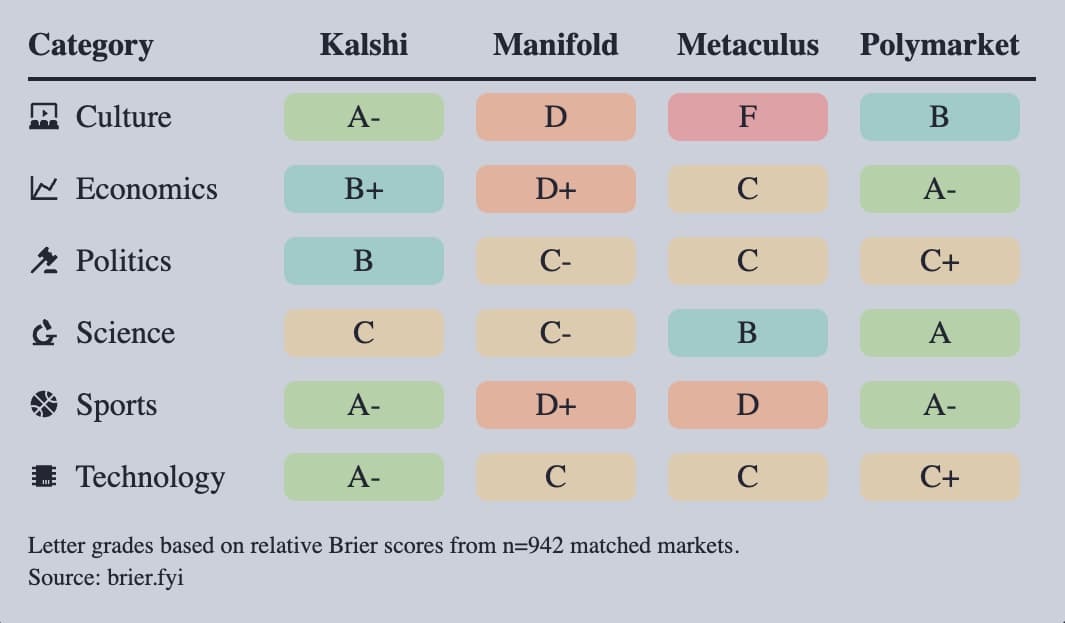

Can prediction markets predict the future more accurately than top experts?

What aspects of dispute resolution need improvement?

How important is the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission? Is a regulatory priority approach the way to achieve widespread adoption?

Is it feasible to compete directly with sportsbooks in sports-related event markets?

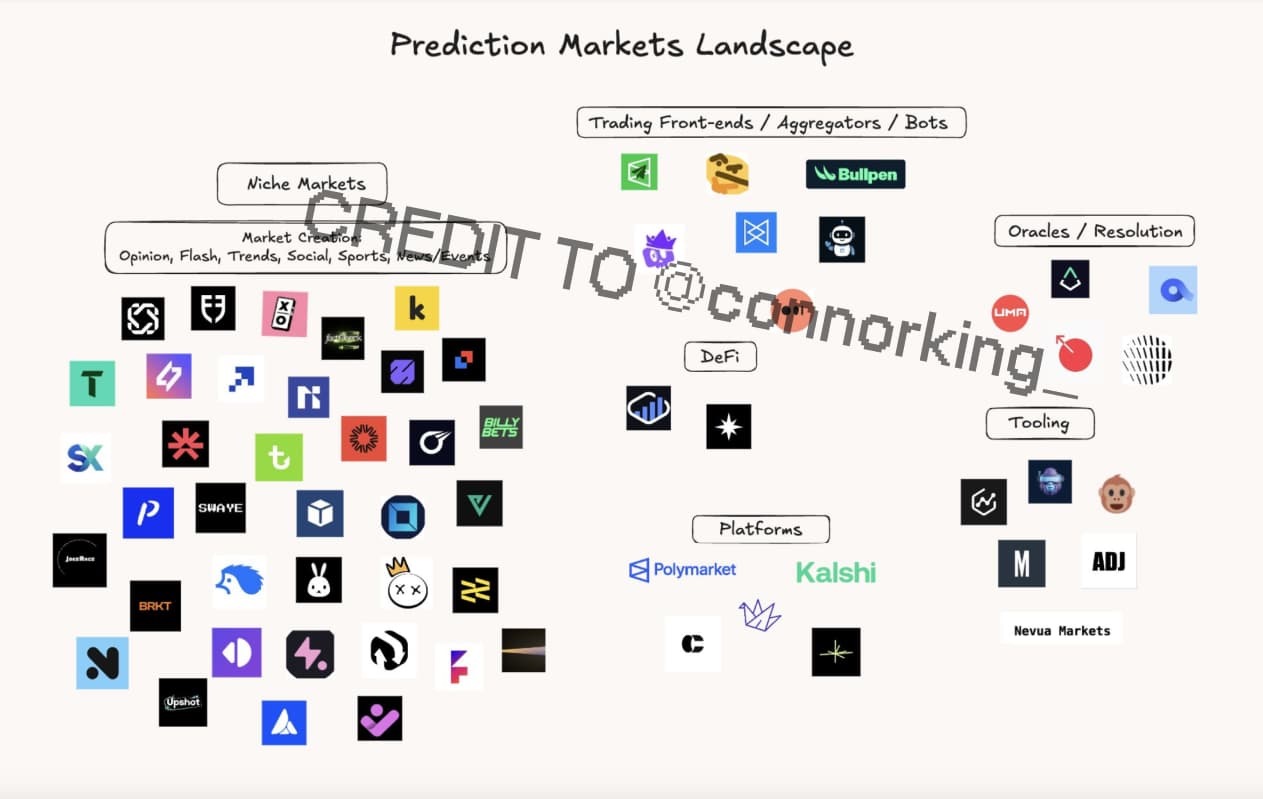

Why do dozens of crypto-native prediction market startups seem to have emerged out of nowhere?

We take a data-driven approach, compiling dozens of hours of research to bring you the most comprehensive report on prediction markets to date. Before we delve deeper, we must clarify a few points.

This report primarily focuses on the usage of Polymarket and Kalshi, as they are the most widely used platforms. This is not to say that existing platforms cannot be surpassed in the future, but because their combined usage accounts for the vast majority of prediction market activity (with 99% of nominal trading volume and open contracts), analyzing the differences between them will best reveal the future of the field.

We are not here to tell you whether prediction markets are or are not the next big trend. We will utilize dozens of sources from various independent publications and reports, freely quoting opinions and presenting information to you while refusing to take sides.

In the words of Aashish Reddy, "Prediction markets provide us with a way to leverage collective intelligence and turn it into predictions that aid decision-making. But based on past conversations, I know you might still be skeptical about this; in fact, for now, you probably shouldn't fully believe it."

How Prediction Markets Fit into the Culture of Speculation

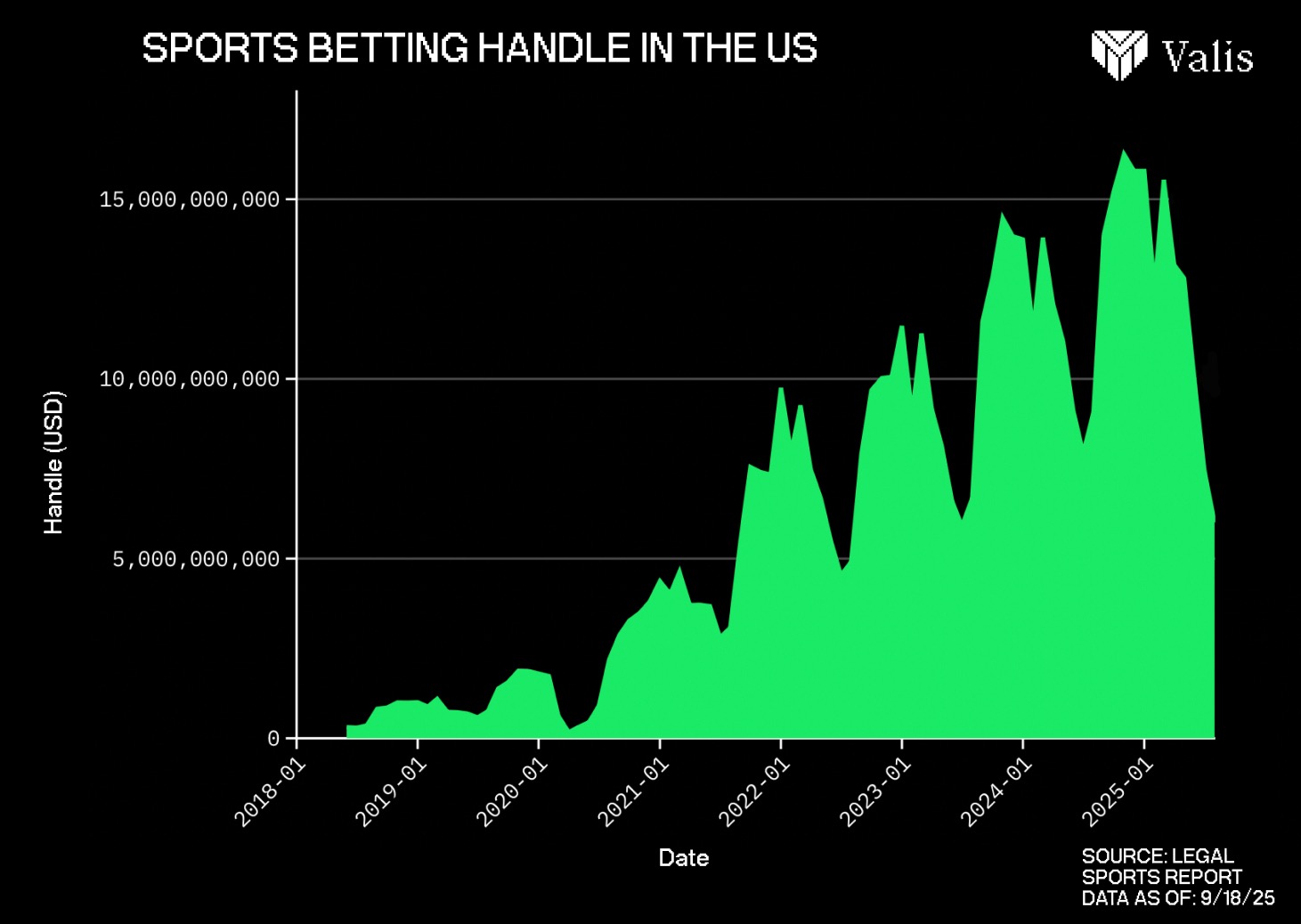

Everyone loves to gamble. Whether it's sports betting, scratch-offs, or slot machines, the global gambling market is vast and continues to grow, despite the unchanging reality that the house always wins. According to Legal Sports Report, since the legalization of sports betting in the U.S. in 2018, the total amount wagered has exceeded $500 billion, generating billions of dollars in revenue for states along the way.

When you watch a professional sports game, you can't help but see odds, player bets, or betting-related predictions from television analysts. Advertisements frequently bombard you with promotional messages directly from these sportsbooks (mainly FanDuel and DraftKings), using household names like LeBron James to mask the harmful realities of gambling. Just in New York and New Jersey, this has generated over $11 billion in tax revenue, with annual revenue growing exponentially in just seven years. Given the profitability of sports betting for states that allow it, it is unlikely that sports betting will be criminalized again, even though the negative externalities of widespread gambling have yet to be considered.

We can assume that gambling has more or less become a daily activity for tens of millions of Americans (over 30 million in 2023), presenting us with a world where gambling is not only permitted but has become normalized.

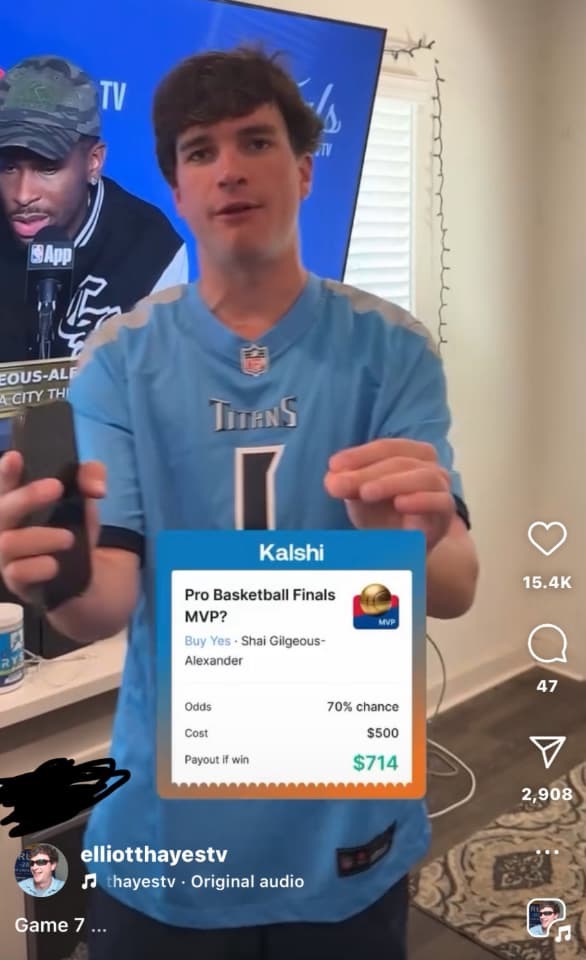

Sports betting serves as the best analogy for prediction markets; while not perfect, we will use it to illustrate how and why prediction markets have become more popular. Additionally, while the payout structure of prediction markets is similar to binary options, and sports betting is based on odds, there is an overlap in user demographics, and the thought processes behind both types of betting are quite similar.

People don’t want to learn how to make money; they just want to make money.

If a devout Republican read a headline in October 2020 stating that Donald Trump had a 40% chance of winning the election, they might have scoffed and complained about the mainstream media being out of touch with their personal worldview.

At that time—just five years ago—the individual mentioned above likely did not know about prediction markets and would not have known they could bet their money on something as significant as the U.S. presidential election, but today we live in a different world.

At the end of 2024, the same person could have bought a $100 share of Trump for $0.40, hoping to achieve a 2.5x return on investment if he successfully won the election, or watch their money evaporate when Kamala Harris's share settled at $1.00, but the outcome is not the point.

The core innovation of prediction markets lies in their ability to convert human beliefs into bets, allowing anyone to stake real money on what they believe to be true. This is human nature and one of the reasons why sports betting has risen so rapidly. Sports are a significant part of many Americans' lives, especially young men, who account for a large portion of sports betting each year, and their share is growing.

As a side note, I can name dozens of college friends and fraternity members who frequently discuss sports betting and place bets every week. This is not to shame anyone, but rather an observation made by a 23-year-old about a trend among peers.

Young men's lives are intertwined with sports, and it can be said that professional sports rank quite high on their list of hobbies or pastimes. If you spend countless hours outside of work tracking professional sports, watching games, and debating outcomes with friends, you are likely to feel the need to make money from it as well.

Those with strong opinions about the Philadelphia Eagles may feel just as strongly about whether Jerome Powell will cut interest rates, but they lack the knowledge or a straightforward way to bet on it accurately through other financial instruments. The average person would never message a sports group chat asking for opinions on the employment report, but they would likely engage in active discussions in the chat rooms of Polymarket.

The logic of making money from areas where one feels they have an advantage can extend from sports betting to prediction markets, with one small detail differing: the addressable markets are virtually limitless. Whether it’s politics, global events, or pop culture, there is always a corresponding market on Polymarket.

Major Speculative Channels

Before diving deeper into prediction markets, let’s first discuss cryptocurrency.

Buying cryptocurrency is easier now than ever. For years, you could buy Bitcoin (and other major assets) directly from Venmo or Robinhood, or even through your brokerage account in the form of ETFs. While the process of getting cryptocurrency on-chain can still be a bit cumbersome, for those who know how to do it, it can be completed in less than ten clicks.

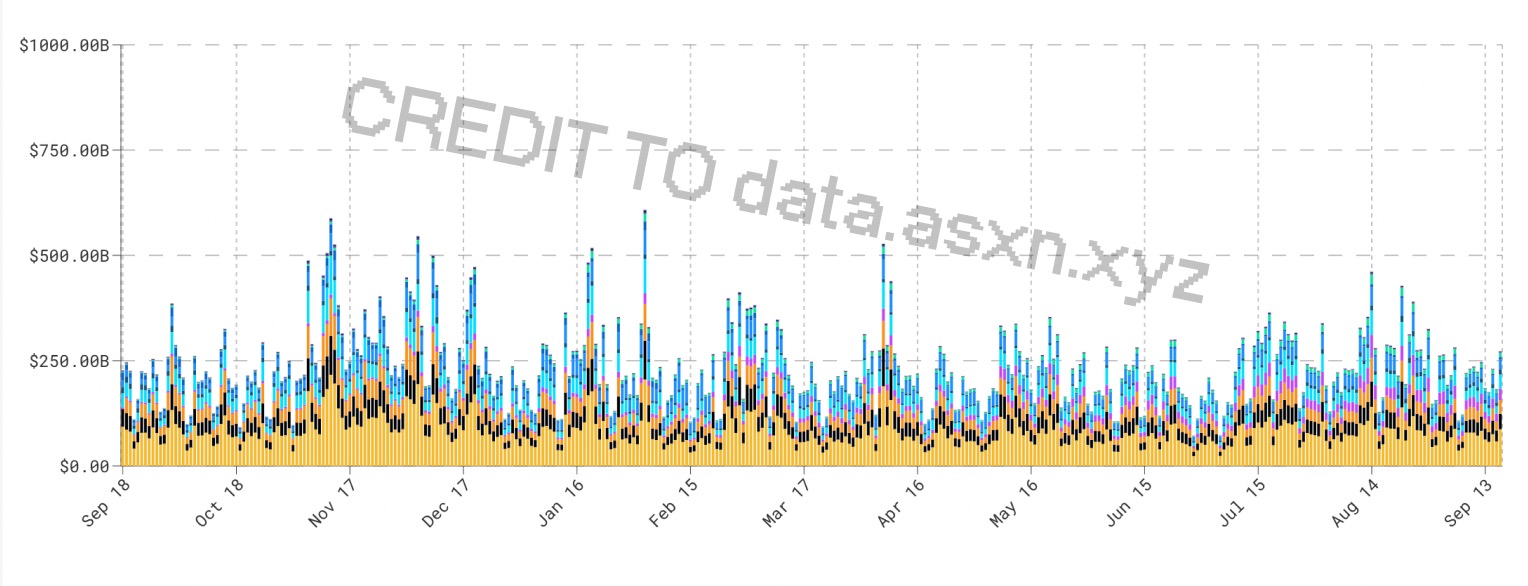

This has led to a significant increase in digital asset trading, a surge in stablecoins, and remarkable performances of assets like BTC and ETH over the past decade. In the largest cryptocurrency exchanges, the monthly trading volume across multiple centralized and decentralized platforms reaches trillions of dollars. The digital asset market is increasingly resembling more complex markets like stocks or commodities, and the number of traders and blockchain users continues to grow.

It can be said that buying cryptocurrency, investing in cryptocurrency, or engaging in short-term cryptocurrency trading is relatively easy, and anyone with internet access can do it. Moreover, while many crypto assets come with utility features, it remains a speculative channel/form.

Returning to the idea that prediction markets will become the next major speculative channel, the easiest comparison lies in the numerous friction points for retail user participation.

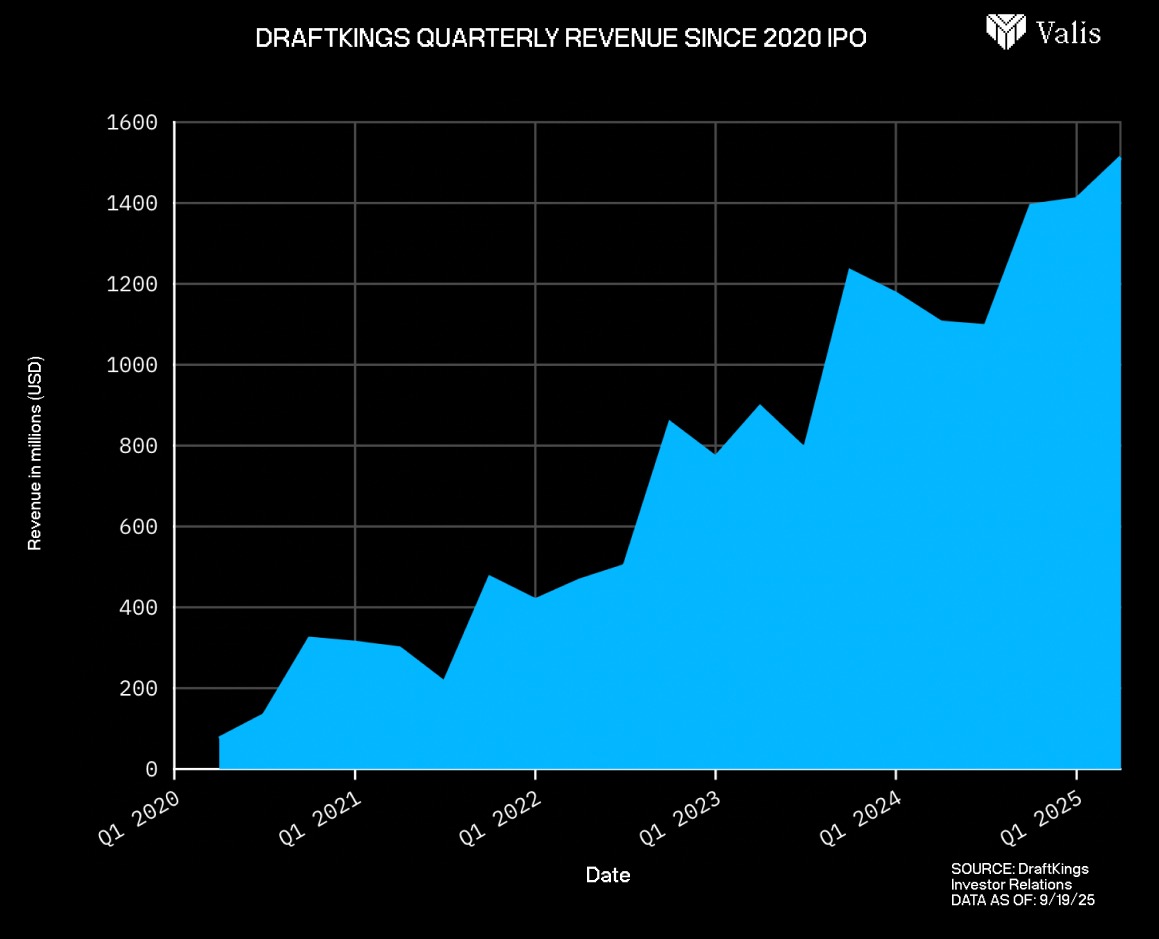

Registering for a DraftKings or FanDuel account is incredibly simple, and deposits can even be made directly through transfer apps like Venmo or Cash App, making it unprecedentedly easy for tens of millions of Americans to "place a small bet." We will soon discuss the actual usage of these services, but specifically, DraftKings has seen its annual revenue grow at a rate of 67% since 2020, with recent second-quarter revenues exceeding $1.5 billion. This growth is also driven by social changes, most notably the recent exodus of residents, businesses, and most importantly—gamblers—from Las Vegas.

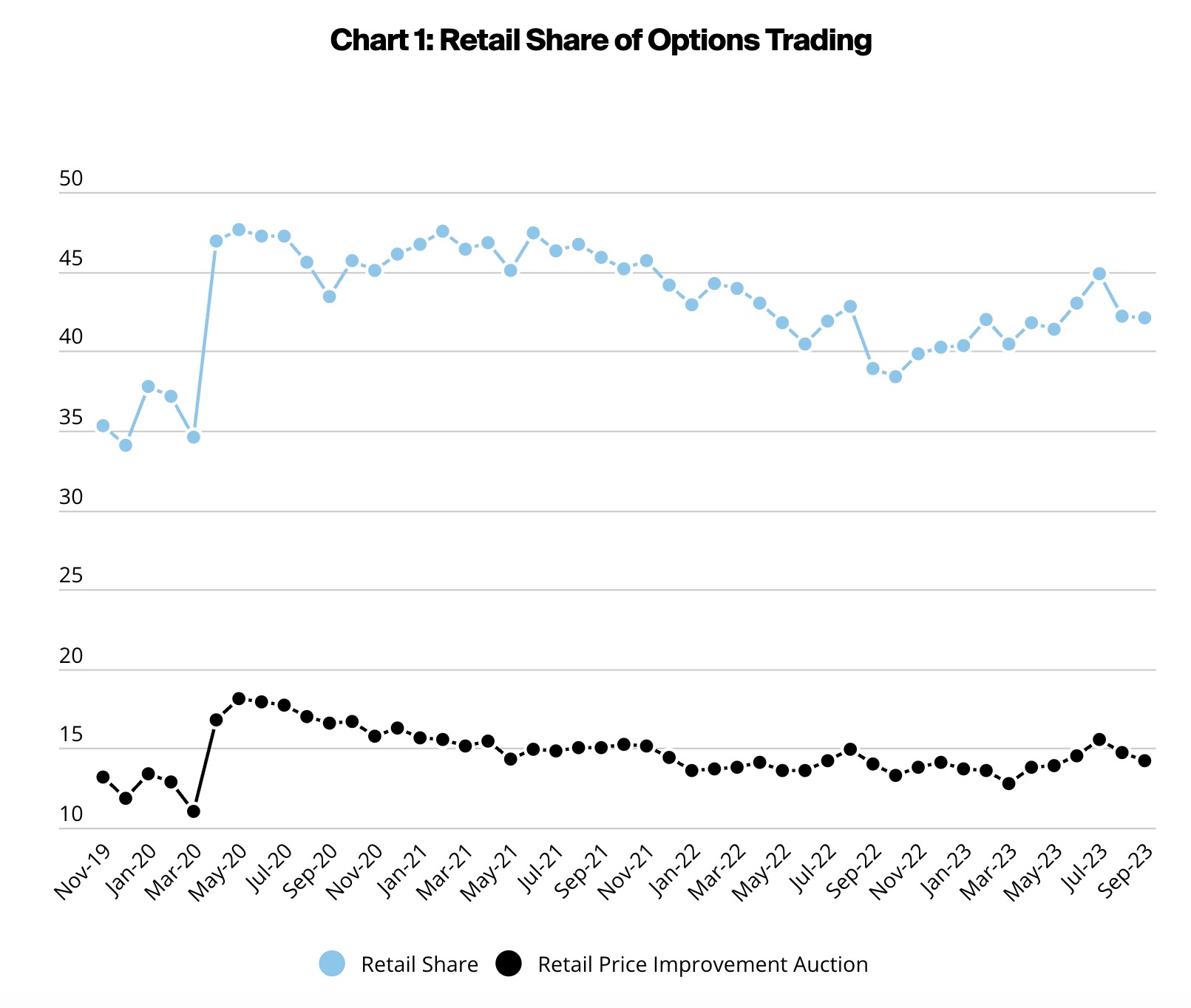

Robinhood popularized the use of stocks, cryptocurrencies, and most importantly—options. You may have heard of /r/wallstreetbets and its massive user base, as well as the huge sums retail traders are pouring into options contracts, particularly the 0DTE options typically associated with meme stocks. But did you realize that the actual trading volume generated by retail options traders is quite high, with retail traders peaking at about 48% of options trading conducted through the New York Stock Exchange in 2023? This is an astonishing figure, especially considering the inherent complexity of standard options contracts, making it a miracle that so many people willingly trade these products.

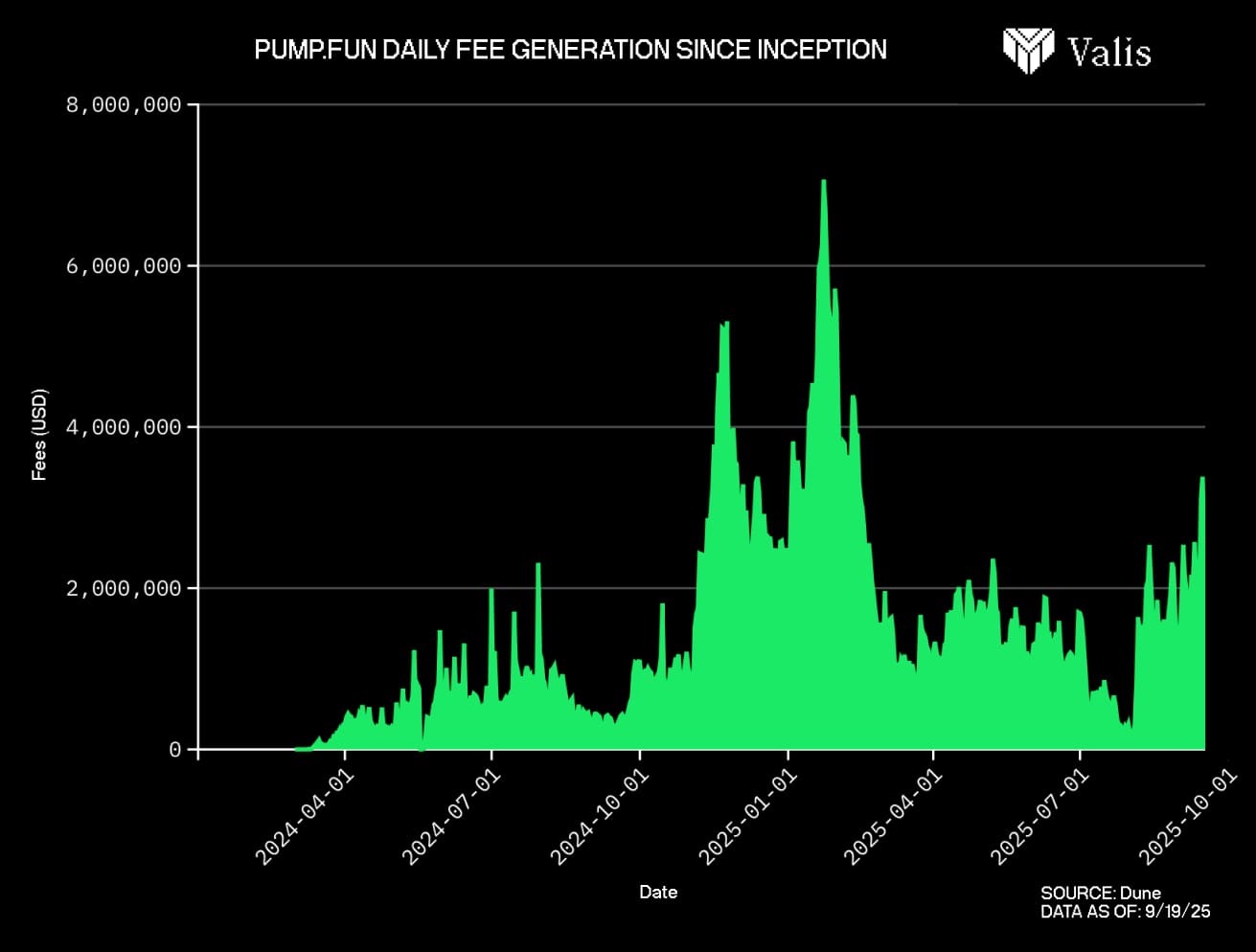

Memecoin trading on Solana remains hot, and at one point, it became one of the most profitable ways to achieve 100-250x returns with relatively little effort (assuming you actually hit one). Platforms like Axiom and pump.fun still generate millions of dollars in revenue each month, although participation has waned since its peak.

However, despite the decline in popularity, it is undeniable that for those with a high risk tolerance and a desire for quick financial freedom, Memecoin represents a more effortless avenue. Most importantly, Memecoin is the first example of retail traders deeply engaging in on-chain trading, with thousands of new traders willing to burn money in search of "gold mines" on social media platforms like TikTok.

So, what do these three speculative channels have in common? The platforms they use allow almost anyone to access a new form of trading or gambling without spending a lot of time learning how to operate.

Negative Externalities of Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are not perfect; in fact, they have generated negative externalities. Similar to traditional gambling, prediction markets have a certain "addictive" quality. Even more so than traditional casinos, as prediction market users may feel they have an "edge" in certain markets. Additionally, participants can directly influence certain markets, opening a Pandora's box of effects on these markets. On the "soft" side, there are instances of people throwing fake phalluses during WNBA games, and that guy who became famous during the Super Bowl, who, despite being fined, made about $374,000 from a $50,000 bet.

The darker side of this Pandora's box is that every market involving specific individual actions effectively becomes an assassination market. Take the case of Charlie Kirk, for example. Theoretically, an assassin could bet on this market and then go kill Charlie Kirk for a reward. This is why "permissionless" prediction markets are so tricky—they essentially create an economic model that allows anyone to hire a hitman with almost no punishment.

The Psychology of Prediction Markets

Prediction markets are still in their infancy, and more work is needed before everyone can participate, but their greatest potential advantage is that users can engage immediately without prior knowledge or educational background. This may be attributed to the wide range of topics available for trading, the convenience of closing positions before outcomes are determined, and even the simplified probability displays that differ from sports betting odds. The reality is that understanding this financial tool is not that difficult.

Human nature is to desire to be right and to prove others wrong in the process. Whether it’s arguing with friends or colleagues about trivial matters, like who will win the Monday night football game, or fighting for a client’s innocence in court, many significant interpersonal interactions take on a binary options form.

I am right, you are wrong. You win, I lose. It’s either double or nothing.

Part of the reason prediction markets are entering the public consciousness is that everyone likes to be right, and everyone likes to make money—platforms like Polymarket or Kalshi can satisfy this innate human desire for correctness and provide tools for the masses to speculate on ideas, beliefs, or strategies that were previously impossible to invest in. Perhaps part of what makes prediction markets so appealing is their simplicity, or that they connect with your brain more than stock prices or options Greeks. Being able to launch Polymarket and bet on whether earnings will drop by 5% or 10% is not only simpler but also more intuitive.

This is where we find ourselves today. The probabilities of prediction markets have appeared on national television programs like CNBC and CNN, sports betting has become commonplace, and the growth of prediction markets continues even after the 2024 U.S. presidential election, unlike the declines in trading volume seen in previous years.

Analysts argue that sustained growth in trading volume or daily active users is a basic requirement, but how do we assess the unprecedented scale of public speculation, the birth of "everything is a market," and the potential formation of the latest financial giants of the 21st century?

Reducible Errors has an excellent post that quantifies what it means for a market to be considered "good," and what characteristics a market must possess to earn that title, including: standardized products, heterogeneous participants, low transaction costs, and a large number of participants. RE effectively highlights many of the most obvious issues surrounding prediction markets and explains why these products will not be quickly adopted by institutions, but the article does not recognize many of the more qualitative benefits.

The view that prediction markets are a poor hedging tool due to their binary nature is certainly correct, provided we assume that the user base consists entirely of financial professionals and elite market makers.

Prediction markets exist in a sort of superposition. On one hand, there is a large group of enthusiasts on platform X who claim that prediction markets are the natural next step for all financial markets; on the other hand, there are professional sports betting experts who firmly believe that this is just another form of gambling, albeit a more complex one.

"Indeed, a financial institution would prefer to hedge with S&P 500 futures rather than a prediction market with a trading volume of less than $5 million, but the situation is different for a pair of college roommates living in a dorm, trading their $50,000 cryptocurrency and meme stock portfolios."

Of course, these two college roommates may be very knowledgeable about futures and understand how to open and manage positions, but depositing $5,000 into Polymarket and opening a hedging position is much easier and less troublesome, especially considering that the average experience on prediction market platforms is far simpler than trading futures.

It is evident that the current state of prediction markets is not suitable for institutions, but it is not easy to present a list of improvements needed to accommodate institutions, which explains why you are more likely to read either glowing praise or sharp criticism of prediction markets. Aashish Reddy wrote that even if prediction markets may be relatively worse than other financial products, "the information demand presented in other fields cannot simply be met by spillover effects from other systems," and their surge is a clear signal that the market values this complement but has yet to reach consensus on its final form.

As you read, keep these questions in mind:

What needs to change? (This is intentionally vague)

How do these platforms scale to billions in monthly trading volume? (Discussions about liquidity will largely depend on the feasibility of this)

Are there any obvious barriers that have yet to be articulated, hindering widespread adoption? (The final section will clarify some of our non-consensus views)

Analyzing Order Books and Market Making Challenges

Liquidity is at the core of any market, and one of the most important topics of this report is to explore the market-making or liquidity provision mechanisms of major prediction market platforms, starting with Polymarket.

The document clearly states that each pair of event outcomes on Polymarket is fully collateralized by $1 of USDC, and on-chain verification occurs when both parties agree on the probability. It is important to note that on specific prediction market platforms, you will find various types of markets.

Baheet analyzed the types of prediction markets in a recent article, explaining that a platform's functionality depends on its specifications across five different categories: liquidity model, outcome resolution, market type, event creation mechanism, and underlying infrastructure, all of which will be discussed in detail later. Currently, we are most interested in his definition of market types, as this is foundational information.

The three types of markets you will find across platforms are binary markets, multi-outcome markets, and scalar markets.

Basic Market Making and Market Formation Scenarios

A basic example of a single market on Polymarket might be two parties holding opposing views on the 2026 NBA Finals champion, with the Miami Heat and Golden State Warriors priced at $0.50 each, indicating that both teams have a 50% chance of winning.

Setting aside the fact that this matchup is highly unlikely, the reality of most prediction markets is that a clear favorite might be priced at $0.47, the runner-up at $0.46, while many other candidates, due to their much lower chances of winning, are priced around $0.01. For simplicity, let’s assume this market was created a week before Game 1 of the NBA Finals, meaning only these two teams are competing.

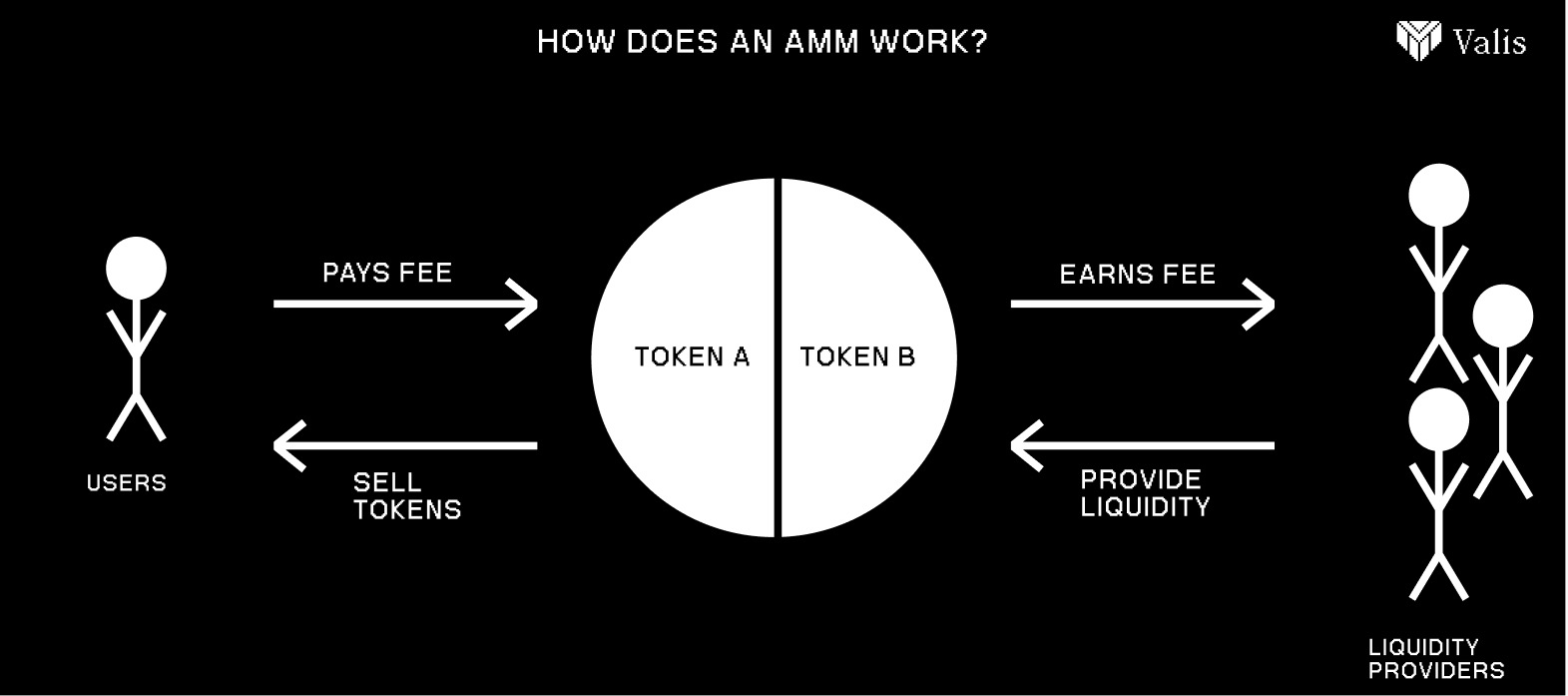

Polymarket previously provided liquidity based on an automated market maker (AMM), meaning anyone wanting to provide liquidity could deposit their USDC into the AMM and support both sides of the market, in this case, the outcome tokens for Miami and Golden State. It should be noted that an AMM is a design for a decentralized exchange where smart contracts on the blockchain manage buy and sell prices, rather than having humans place orders directly on an order book. AMMs have created wonders for cryptocurrencies, but Polymarket's brief attempt symbolized the shortcomings that this technology still faces.

Polymarket later abandoned this model because liquidity providers essentially took long positions on both sides of the market in equal proportions, exposing them to inventory risk and making market making more frustrating than it should be. They subsequently switched to an order book model, similar to the type used by Kalshi and countless other exchanges.

Markets are formed from a viewpoint, and liquidity follows. Regardless of how the liquidity structure is set up, this is the core foundation that allows event markets to operate.

Liquidity must first be seeded by market makers who set their own odds. Suppose a market maker acts first, setting an order to sell 1,000 shares of Miami YES at $0.50, and an order to buy 1,000 shares of Miami YES at $0.48. This would be the first liquidity offered for the outcome of the NBA Finals, which users can then transact against. If a user decides to fill this market maker's sell order and submits an order for 500 shares of Miami YES, they effectively hold a long position of 500 shares of Miami YES, while the market maker holds a short position of 500 shares of Miami YES.

Suppose another market maker enters and wants to compete, this time submitting an order to buy 1,000 shares of Miami YES at $0.49, and an order to sell 1,000 shares of Miami YES at $0.51. The order book would look tighter due to the added liquidity, meaning the user could buy 500 shares from the original market maker at $0.50 before needing to purchase 1,000 shares from the second market maker at $0.51.

From here, the operation of prediction markets works like any other financial product, where more buying of the underlying asset pushes its price up while simultaneously lowering the price of another asset in the process. Depending on the outcome and position, you might make a small profit, a large profit, a small loss, or lose everything. If Miami wins the championship, anyone holding those shares will see their value rise to $1 per share; however, if Miami loses, the trading price of those shares will drop to $0.

This is the simplest explanation of liquidity provision in this report, and if you are still a bit confused, you can read more in the Polymarket documentation before continuing.

In terms of market making, Kalshi's market creation system is broadly similar, except that the collateral does not use USDC and does not operate on the blockchain.

To create a market on Kalshi, it must be initiated directly by the team, started by a creator approved by the exchange, or suggested by a user and ultimately reviewed. Polymarket events can produce mutually exclusive outcomes that are bundled together and collateralized at $1. For example, $1 can be bet on the odds of five different teams winning the NBA Finals, or the odds of five different candidates winning an election.

On Kalshi, each outcome is an independent binary (yes or no) contract, and the market is created by bundling all these binary contracts together and presenting them as a single market in the user interface. This does not affect the end user; although the market for the 2028 U.S. presidential election is displayed similarly on Polymarket and Kalshi, the underlying structures are very different, with some major distinctions. The multi-outcome markets on Kalshi functionally remain the same as those on Polymarket, just constituted under a different set of circumstances.

Since each market on Polymarket is fully collateralized by $1 USDC, the sum of probabilities must always equal 100%. Kalshi differs in this regard; when these binary contracts are stitched together, the sum of probabilities may not exactly equal 100%, creating arbitrage opportunities. This does not mean that Kalshi's markets are not fully collateralized, but rather that their construction differs from Polymarket, leading to various strategies that are used exclusively on Polymarket or Kalshi.

Although these examples make it seem simple, the market making and liquidity provision on these platforms are much more complex and far from the black-and-white description we currently provide.

Some Data Metrics

Before analyzing market making dynamics, let’s first observe some more general metrics, such as trading volume, open interest, number of trades (where applicable), and daily active users, to depict the current state of these platforms in their quest for more users.

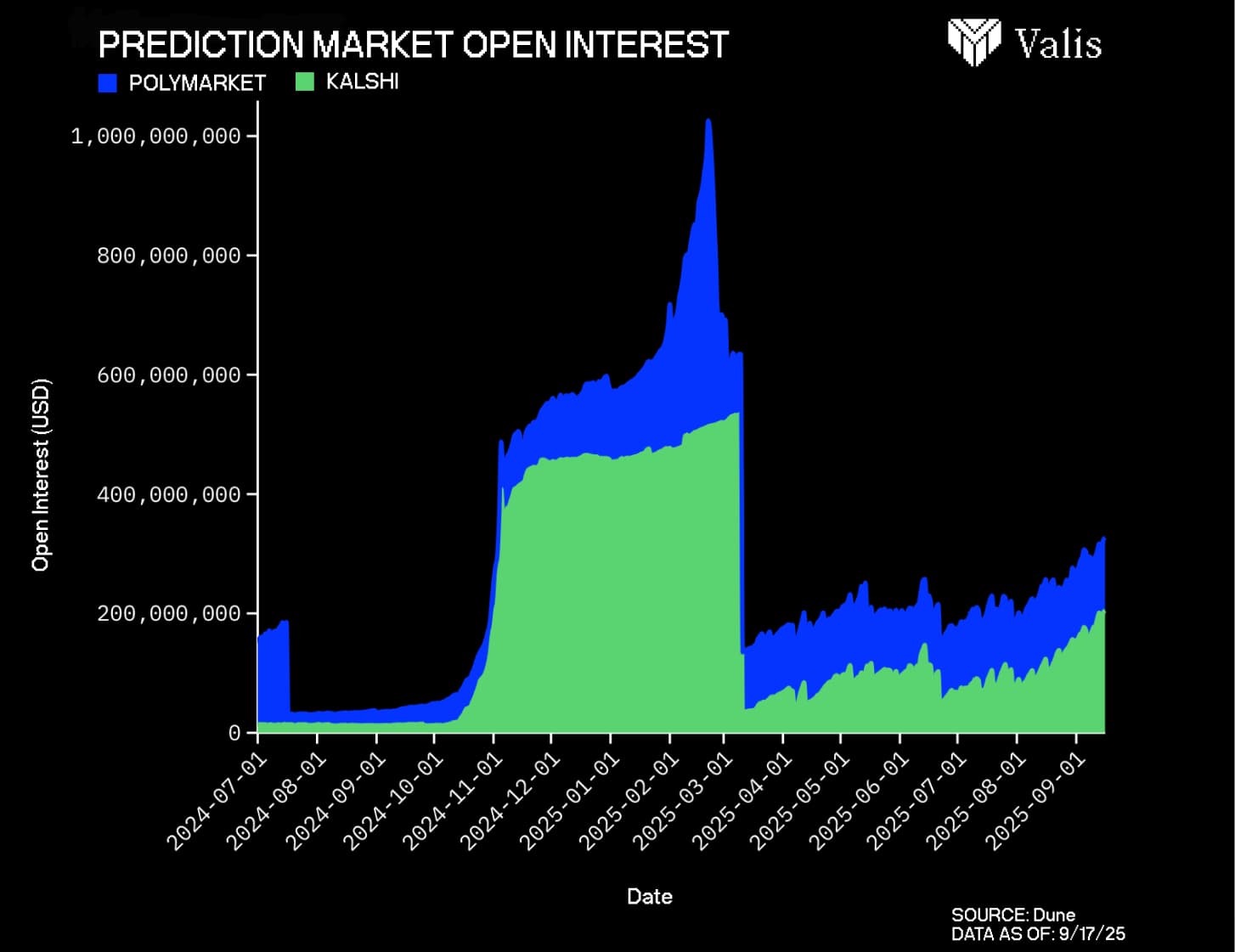

Of the total trading volume of $34 billion since its inception, approximately 79% comes from Polymarket, while about 21% comes from Kalshi. There has not yet been a clear competition between the two in attracting market makers or retaining liquidity; however, as we will discuss later, some recent strategies from Kalshi have put pressure on Polymarket's once considerable market share advantage. Recently, viewing weekly nominal trading volume through Dune, Kalshi's market share has grown from 8% in January 2025 to just over 62% in September 2025.

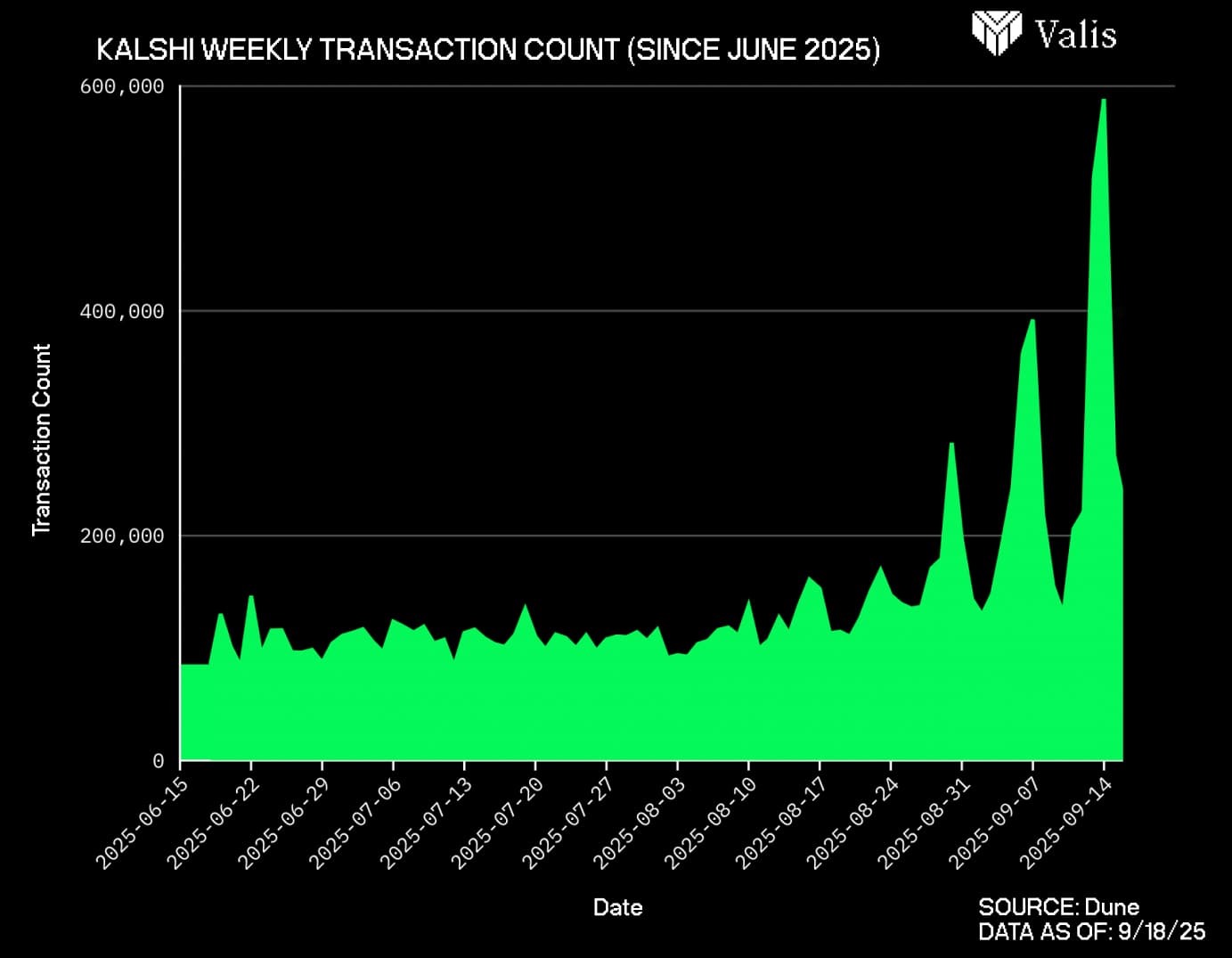

The number of users on Polymarket is visible since it is a blockchain-based application, while Kalshi is a centralized application, meaning the number of trades is a better indicator of actual usage. According to data from Dune, Polymarket has accumulated 61 million trades since its inception, while Kalshi has 30 million trades. The number of trades on Polymarket is twice that of Kalshi, which is due to Polymarket's longer existence, while Kalshi has only recently begun to gain attention.

This is not to belittle Kalshi; we must point out that although Kalshi lags in cumulative trades, its recent growth far exceeds that of Polymarket.

Looking back over the past three months (up to June 1, 2025), Polymarket's average daily trades were about 147,000, while Kalshi averaged 142,000, an increase from the average of 24,000 in February 2024. If we look at more recent data and focus solely on September, Kalshi's average trades for the first 18 days of that month were 260,000, while Polymarket had 161,000 daily trades. This is primarily attributed to Kalshi's focus on sports-related markets and the growing "sports-first" mindset.

We have discussed that sports betting is a huge industry and continues to grow, but it is becoming increasingly clear that this growth needs to be viewed in conjunction with Kalshi's significant push into the sports betting space and its impact on both industries.

DraftKings is one of the largest online sports betting companies in the U.S. and is also a publicly traded company, allowing us to gain insights into its historical revenue. The data in the following chart is sourced from DraftKings' investor relations page; of course, we cannot access the latest data since the start of the 2025-2026 NFL season, as this information will not be released until the third-quarter earnings report. If Kalshi continues to eat into the betting volume and user base of traditional sports betting, this data will showcase its potential development trajectory or a more realistic growth pattern.

Regarding this encroachment, Kalshi has been quite active. Adhi Rajaprabhakaran reported that Kalshi submitted a new application to the CFTC on August 18, requesting explicit permission to launch player betting and point spread betting, taking a step further than more traditional odds betting or futures contracts.

Kalshi's Sports Betting Ambitions

It is easy to see that Kalshi is very aware of the growing dominance of the sports betting market, so submitting such applications is a logical step. Currently, about 80% or more of Kalshi's weekly trading volume comes from sports-related markets, performing quite well.

One underestimated advantage of using Kalshi compared to other sports betting platforms is the absence of any penalties or fees for early cashing out. Closing a position on DraftKings can lead to a loss of 25-30% of the bet amount, especially if the game has already started. On Kalshi, cashing out depends on liquidity, current prices, and other factors like potential short-term volatility, but it is far smoother and less frictional than any alternative.

We could elaborate extensively on Kalshi's efforts to advance and further penetrate the sports betting market across the U.S., but the reasoning behind its decisions is best captured by this excerpt from the same post referenced above: "The entire revenue model of sports betting relies on high commission markets and the ability to analyze and limit professional bettors."

It is well known that if someone performs too well in sports betting, they are likely to be banned from the platform. This has led to many different workarounds over the years, but in stark contrast to this commission model, Kalshi and Polymarket have no incentive to ban their top traders because they do not act as "bookmakers."

This is a question worth exploring, especially considering the recent comments from Kalshi's head of development regarding its internal market-making team (known as Kalshi Trading) commenting, particularly: "Market makers, including KT, compete for flow in an open, transparent, and fair market, setting their own prices for the contracts they are willing to pay, but beyond that, they cannot dominate the broader market."

We cannot confirm or deny whether KT or other market makers receive preferential treatment, as such data is not available, but this conflict of interest has raised concerns among many, and its implications are well summarized here: "Kalshi claims that market makers cannot influence the market despite fee rebates, which is one thing, but simultaneously exercising economic power in those same markets to undermine competitive pricing while making such claims is far more serious."

It can be speculated that professional bettors will gradually be attracted to Kalshi rather than risk it on traditional sports betting platforms, especially if market makers can receive more favorable rebates or kickbacks in any form.

But has this situation already begun? It is currently difficult to draw conclusions.

Dustin Gouker from The Closing Line published a weekend data summary on September 8, showing that Kalshi's trading volume reached $300 million, with an astonishing 96% coming from sports events, and NFL football alone accounting for 84%. This is not only impressive for a prediction market platform but can even be said to rival mid-tier sports betting platforms.

Of course, this does not mean that Kalshi can immediately compete with giants like DraftKings or FanDuel, nor does it mean that all existing platform customers will switch to Kalshi, but it is hard to ignore that Kalshi, with its more favorable regulatory positioning with the CFTC, can promote its products across all 50 states in the U.S. Considering that sports betting is not legal in all 50 states and that states allowing betting can generate huge revenues from it each year, it is not difficult to understand why seven states that support betting have recently issued cease and desist orders to Kalshi. Benjamin Sturisky explained how Kalshi is able to circumvent regulators and provide its services without repercussions: "Because Kalshi is a third-party provider with no economic interest in the outcomes of events, they are classified as a peer-to-peer platform rather than a sportsbook."

Kalshi is rapidly advancing, breaking conventions. Another angle here is whether analysts can use Kalshi's activity data as a reference for predicting DraftKings or FanDuel's quarterly earnings. This is likely an original idea you won't find elsewhere. But we are not exaggerating; we believe this seemingly bold proposal has merit.

Gradually Incentivizing More Liquidity

We have discussed that Polymarket and Kalshi have different strategies for injecting liquidity into new markets, but these platforms also differ in how market makers exist throughout the market lifecycle, and their incentive structures reflect this most clearly.

We can examine the most basic competitive aspects through existing data and closely study liquidity incentives and targeted incentive distributions, as these are the two most relevant drivers of trading volume for Kalshi and Polymarket.

Regardless of the market, there must be incentives for participation, whether you are a market maker, retail trader, or an institution taking a position on something. As mentioned earlier, market making in zero-sum prediction markets is a challenging game and is often considered the most important bridge to cross before introducing more users, more institutional trading activity, and more trading volume.

Polymarket recently created a liquidity incentive dashboard, which is a nice initiative aimed at attracting more amateur market makers and clearly outlines the requirements and associated rewards for them.

The dashboard lists the maximum allowable spreads, USDC rewards, competitiveness of each individual market, and existing prices. This is a good start, and it is clear that incentivized markets will certainly become popular at some point (although it is currently difficult to kickstart, and all trading liquidity is low). At a high level, here is a basic description of how Polymarket determines liquidity rewards:

The closer to the average price = the more you earn

The reward amount depends on how "helpful" the order is in terms of size and pricing to others

The stronger the limit order competitiveness, the more you earn

Daily payments based on how much the order contributes to the market

The actual formulas for these platforms will soon be involved, but keep in mind that Kalshi's market incentive situation is untraceable; however, we can infer and build a mental model of which markets would receive the most incentives if we were to operate Kalshi.

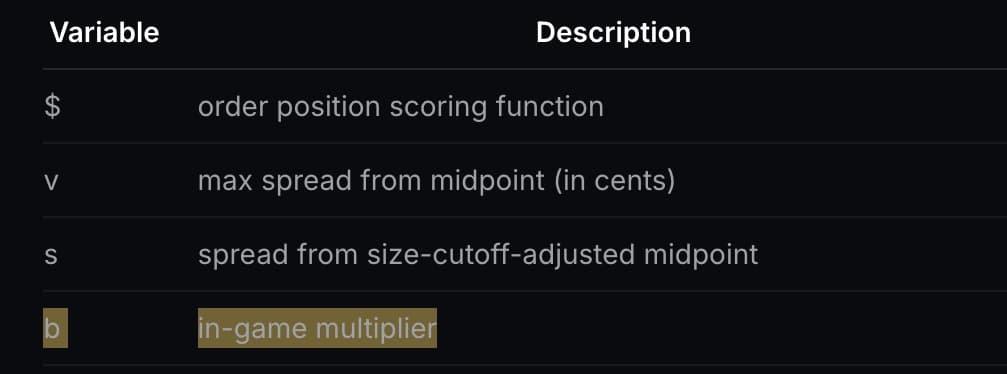

Take a look at Polymarket's developer documentation, which includes a list of variables and their accompanying functions, among which the most interesting is the b value and its role as an in-game multiplier.

We know that both platforms can "boost" liquidity rewards, but it is difficult to say when this occurs and in which markets. Despite this information gap, we can still observe the open contract metrics of these platforms and conclude that neither's rewards are exaggerated enough to squeeze out competitors.

As of September 17, the total open contracts across all markets on Polymarket and Kalshi exceeded $370 million, a significant drop from the combined open contract peak of over $1 billion in Q4 2024, but showing a clear strengthening since the beginning of this year:

Notably, although open contracts have decreased by over 60%, this has not prevented trading volume from approaching historical highs. In fact, regarding the U.S. presidential election, many people are simply holding positions in shares of Trump or Harris rather than trading more short-term markets back and forth. While trading volume is evidently high, we are now seeing different dynamics, with more markets being traded, and due to the unmatched importance of the presidential election results, trading dispersion is common.

The distribution of open contracts held in political markets and their continued lead can be explained by the significant far-reaching impacts associated with U.S. elections, but also because politically charged content is very prevalent on social media platforms like X, where Polymarket and Kalshi frequently utilize the platform for advertising and press releases.

Another situation is that due to the abundance of data online, political prediction markets are relatively easier to market, although this question cannot be answered without directly speaking to market makers. Additionally, not all liquidity is equal; just because one platform has over $100 million in open contracts does not mean that platform has uniform liquidity.

The 2024 U.S. presidential election is the strongest driver of liquidity and trading volume across all platforms and has consistently been the peak of prediction market activity. This market once had over $150 million in open contracts, considering that Polymarket's open contracts were $300 million on October 29 last year, representing over 50% market share.

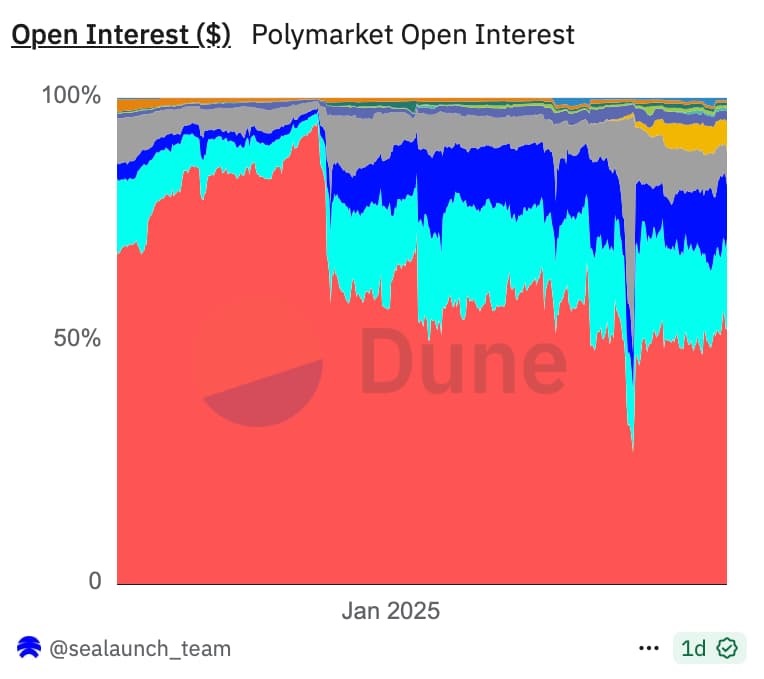

Here is the current status of open contracts on Polymarket categorized, referencing the dashboard created by @sealaunch_:

We see the distribution of open contracts across categories such as cryptocurrency (light blue), other (gray), business (light purple), sports (dark blue), and politics (red), but this severe bias towards a single market is not the norm. Even though the political category maintains about 50% of Polymarket's open contract share, there is a healthy distribution in non-sports categories.

How do these platforms incentivize liquidity in non-political markets, or categories that may inherently be more unpredictable and long-tailed?

Solutions for Liquidity and Their Necessity

Yoshi wrote a short article proposing five unique solutions to the liquidity issues in prediction markets, with the most interesting aspect being that each idea targets different facets of the prediction market space. These include proposals to introduce more futures and options market makers, introducing bonding curves similar to those used by pump.fun to guide liquidity for long-tail prediction markets, and other basic proposals that seem quite realistic and achievable even in the short term.

You might wonder why this even needs to be discussed: if the mechanisms for guiding liquidity or improving liquidity distribution are so obvious, why haven't they been implemented?

That's a good question, but it does not recognize the current situation of Polymarket and Kalshi. Remember that over 90% of Kalshi's trading volume in September 2025 came from sports? If you are a platform seeing significant growth in a specific category's trading volume, you might be more inclined to incentivize that category in the future.

Dustin Gouker posted on X that Kalshi is hiring for two sports-related positions, one of which requires "extensive experience with sports betting platforms—understanding how they operate, common market types, settlement procedures, and edge cases that arise in sports market operations," which credibly indicates this is the direction they are developing.

After all, since legalization in the U.S., sports betting trading volume has exceeded $500 billion and remains a preferred pastime for young men; why not compete head-on with some of the largest sports betting platforms?

You need to make market makers feel not only that their work is compensated but also that the compensation is sufficient to deter them from moving their business to another platform or competitor. From a risk/reward perspective, the incentives should be quite high.

Reducible Errors puts it best: "For binary options, assume the market trading price is around 50%. If you short a lot and the outcome settles as 'YES,' you will incur heavy losses, and vice versa. But you cannot take any measures to reduce the risk. All you can do is hope."

Simply offering more incentives than competitors is one way to maintain liquidity, but given the risks involved, retaining them is more important, especially considering this undeniable reality of adverse selection.

A necessary rebuttal comes from the fact that sports betting platforms are ideal for market makers because they present both the allure of uninformed retail capital flows and a more predatory incentive structure. It is foolish to think that market makers would not take on a small inventory risk on platforms like Polymarket or Kalshi to gain access to a large flow of uninformed retail traffic (along with favorable fee structures or rebates).

Yoshi's suggestion to introduce more futures and options market makers may be the clearest short-term solution to the liquidity stickiness problem, as both have similar payment structures. However, considering the risks that non-professional liquidity providers may face in any specific prediction market, this suggestion is also quite necessary. Since these market makers have experience managing inventory risk and possess the skills to accurately simulate volatility in new markets, their presence could narrow spreads, but their complexity has yet to be mainstreamed on these platforms.

This makes sense theoretically, but it is worth noting that even if these market makers enter prediction market trading with knowledge from other industries, they cannot achieve a 1:1 conversion given the difficulty of hedging binary prediction market outcomes. Futures and options market makers can utilize countless strategies, tools, and financial engineering techniques to hedge any risk, but doing so in the existing prediction market space is quite challenging, if not nearly impossible.

In other liquidity proposals, Yoshi points out that bonding curves promoted by pump.fun and its memecoin liquidity guiding model are a potential avenue for any platform seeking to incentivize long-tail liquidity. We note that Polymarket initially adopted an AMM model for market guidance before shifting to a primarily order book-based system: What if a smaller or riskier subset of markets on Polymarket adopted bonding curves like those of pump.fun?

This is an understandable solution, as any long-tail event carries significant market-making risk (see: Will aliens visit Earth in 2030?); however, if more speculative individuals wish to see greater potential returns on Polymarket, the entire platform would benefit.

To quote Adjacent again: "When a market is newer, niche, small, and has low liquidity, utilizing AMM curves is often very helpful. Liquidity providers typically provide passive liquidity to the AMM, ensuring that traders always have a price at which they can sell."

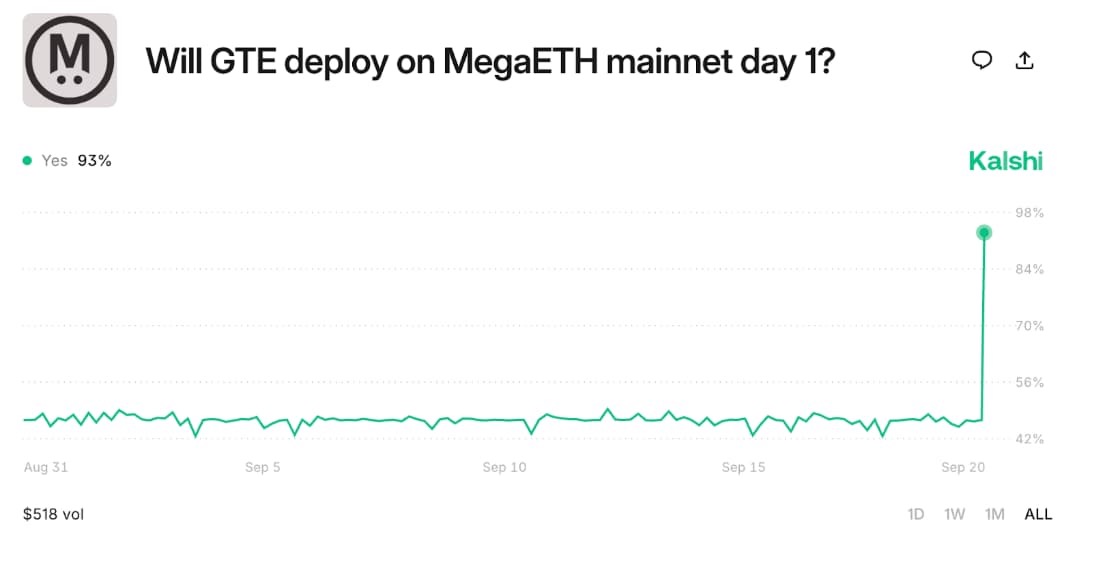

A good example is the market below, where approximately $241 was used to push the event contract price from about 0.4 to about 0.9. Very interesting. For those unfamiliar with the situation, you can refer to the GTE team's tweet about their departure from MegaETH.

A smaller proposal is to implement outcome-based settlement incentives, meaning that market makers' incentives are only allocated (or attributed) after specific market outcomes are revealed. This would curb wash trading and allow the platform to incentivize early liquidity (by adopting asymmetric reward distribution ratios during the market launch phase), but it would require manual oversight of which markets are best suited for this mechanism.

Regarding the topic of wash trading or minimizing market maker misconduct, Kalshi recently introduced a new incentive structure aimed at encouraging all markets to provide deeper and more consistent liquidity, which is the right direction for addressing liquidity issues.

Kalshi's new liquidity program defines three parameters for each qualified market it designates. These parameters are target size, discount factor, and time period rewards.

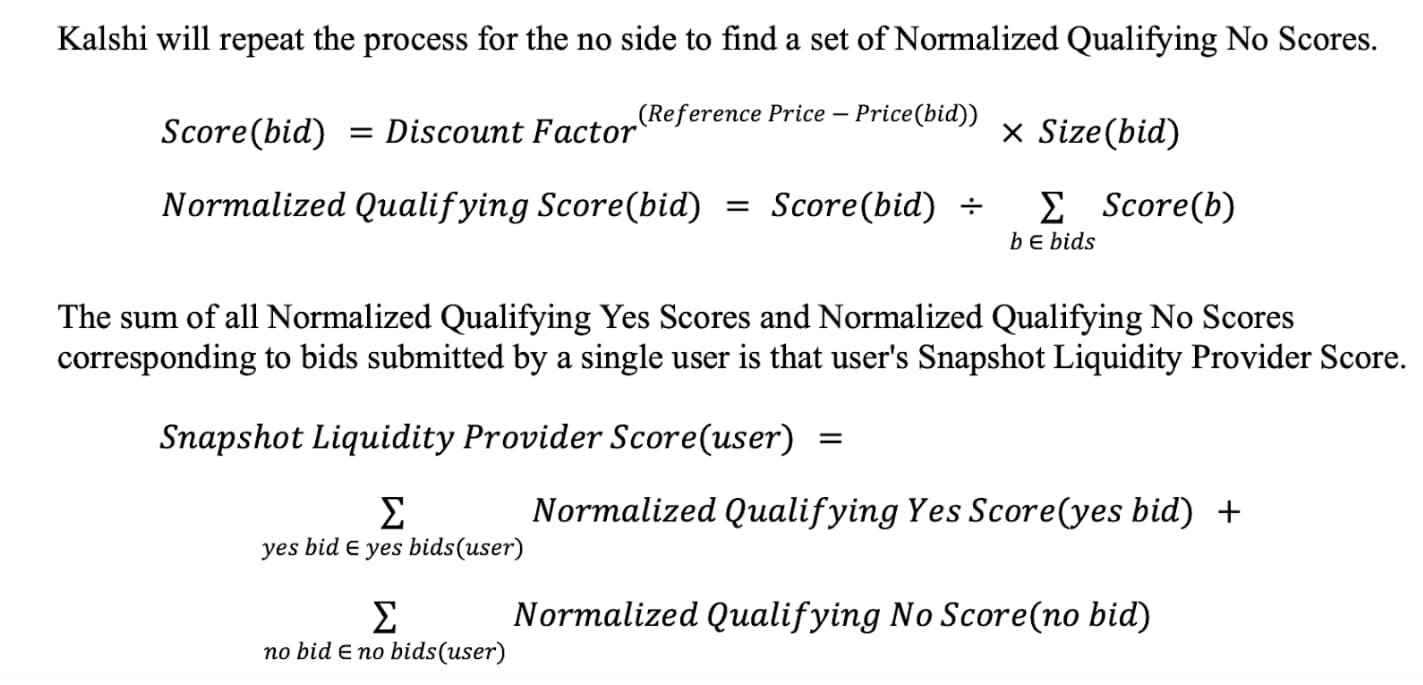

Taking Adhi as an example, an aspiring market maker might place an order for 1,000 contracts in a market with a discount factor of 0.9 and a reward pool of $100. These 1,000 contracts could be distributed across three different price points (the optimal bid, one cent off, and two cents off), representing three different payout structures for that order. The calculation is theoretically quite simple: multiply the size by the discount factor and then by the power of the distance from the best bid.

This straightforward calculation measures the reward rate for Kalshi market makers, clearly prioritizing tighter liquidity through snapshots taken every second, and curbing mercenary-style market making.

Understandably, Kalshi wants to reward more sticky liquidity, but importantly, this revision makes it difficult to determine what systems Kalshi has in place, as its centralized nature makes it nearly impossible to peek behind the scenes.

Recently, rumors have intensified regarding specific market makers enjoying zero fees or zero rebates, although the specific details remain uncertain. SIG was the first institutional market maker to join Kalshi (in April 2024), and we are not here to discuss the business acumen of these teams, but it would be absurd to think that SIG would not agree to such practices and not provide some form of preferential treatment. If this sounds a bit exaggerated, just refer to all the replies to this post as a sentiment check.

While we know that front-running is a significant issue in such markets, both Polymarket and Kalshi strongly incentivize market makers to provide two-sided liquidity and impose strict penalties on those who do not comply with this rule.

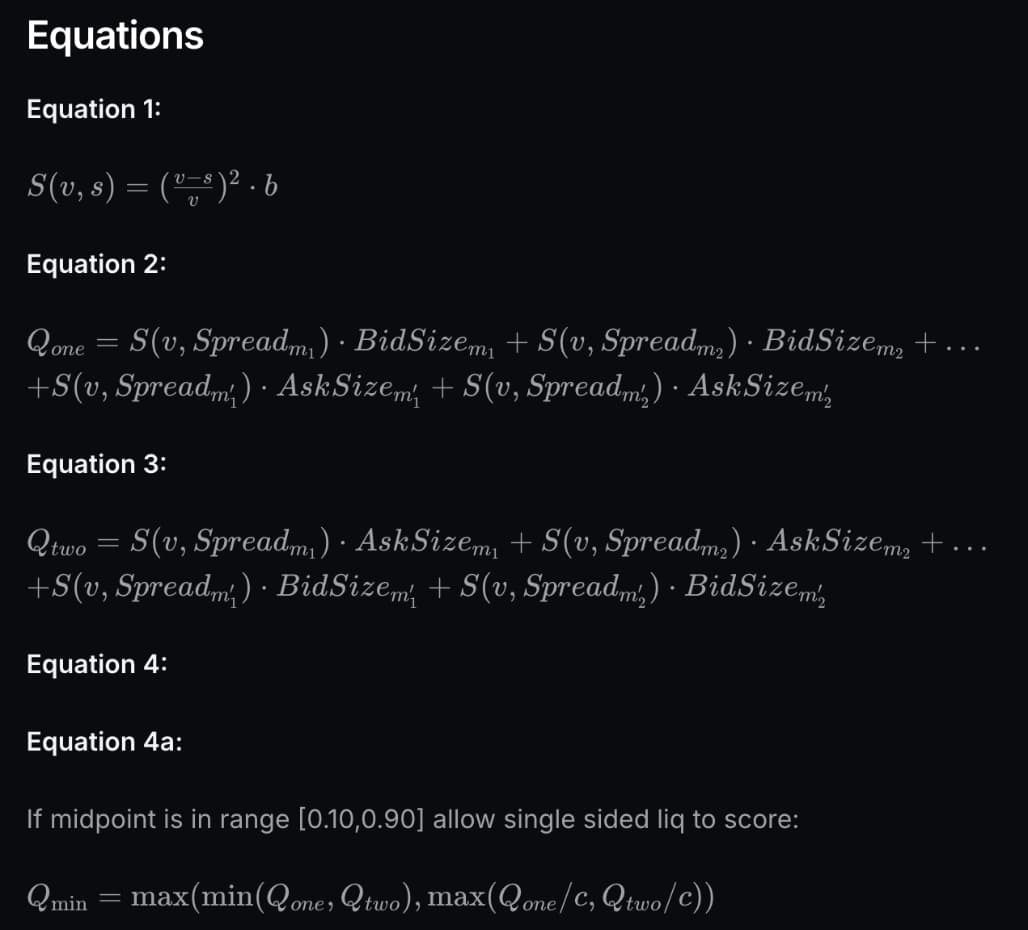

Kalshi incentivizes market makers to provide two-sided liquidity through soft penalties, confiscating from those who do not quote two-sided prices. If a market maker decides to only quote a one-sided price, the earnings on the other side are essentially zeroed out, which greatly incentivizes providing liquidity on both sides of the order book. According to Kalshi's documentation, market makers can only earn liquidity rewards between $0.03 and $0.97. This is reasonable as it curbs speculative behavior that pushes markets to extreme prices.

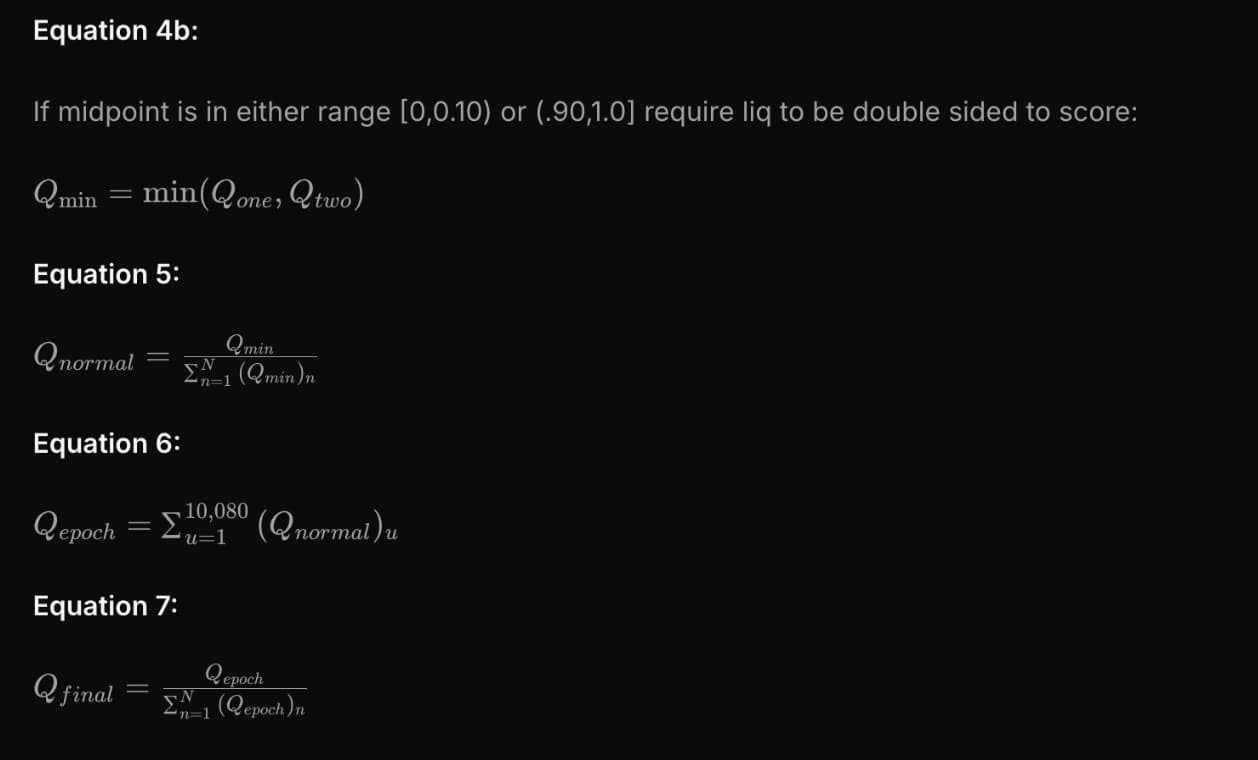

Polymarket's penalties for one-sided liquidity are much harsher. As seen in the formula below, providing one-sided liquidity means that the points you ultimately earn will be divided by 0.3333. Additionally, when the trading price of the token is within the range of [0.1, 0.9], you can only provide one-sided liquidity; if you want to earn points outside that range, you must provide two-sided liquidity.

The conclusion drawn is that Polymarket's penalties for one-sided liquidity are much more severe, which is interesting because, at the same time, the lack of KYC makes its platform more susceptible to insider trading. That is to say, they should be more lenient towards one-sided liquidity providers, as the likelihood of being front-run by insiders on Polymarket is much higher than on Kalshi.

Quoting Adhi from the same post above: "Exchanges do not need to go to great lengths to find and hire a trader skilled in both areas. They can freely choose which markets need more liquidity. Polymarket has enjoyed the convenience of this system for years."

For Kalshi, this is a shift, as their previous model included incentivizing market makers through fee rebates, but this submitted document explains how the restructuring of the incentive system prioritizes trading volume and liquidity. The document also confirms some form of cancellation of the previous rebate program, but does not provide details, merely stating: "For the avoidance of doubt, Kalshi hereby notifies the CFTC that the trading volume incentive program submitted by Kalshi in October 2024, and the fee rebate program submitted in January 2025, are not in effect and are hereby terminated."

Liquidity Incentives and Multiplier Mechanisms

The in-game multiplier mechanism seems to have been replaced by a more decentralized liquidity incentive program. That is, integer rewards are adopted, possibly to simplify the liquidity provision process for market makers. Currently, only 32.3% of active markets have liquidity incentives.

Polymarket spends about $5 million on its liquidity incentive program. Approximately 90.5% of incentivized markets have a daily incentive amount of $5 or less. In sports betting markets, most markets have liquidity incentives close to zero (with a median of $1).

However, some markets related to teams with a high probability of making it to the Super Bowl are receiving heavy incentives, with daily liquidity incentives around $400. This indicates that Polymarket is not genuinely trying to "compete" with Kalshi across all sports betting projects; it is only targeting the markets with the deepest liquidity (like the Super Bowl). This may be due to regulatory reasons, as Kalshi cannot truly offer markets like "Will Company X's earnings per share exceed expectations this quarter?" because it resembles financial products too closely. However, this presents a rather interesting market for Polymarket, as well as a market where they have significant liquidity incentives.

These markets typically open close to their expiration date and can sometimes attract considerable trading volume. COST is currently the market with the highest incentive intensity. Among markets with daily liquidity incentives of $100 or more, 69.5% are politically related, which seems to indicate that Polymarket is more inclined to compete in the culturally relevant/political domain rather than in the sports domain that Kalshi primarily targets.

According to Kalshi's API, there are currently 35 markets offering liquidity incentives, with all but two being sports markets. Since its inception, Kalshi has spent $8.75 million on incentives, with a current daily expenditure of about $35,000, nearly double that of Polymarket. By the way, this website lists 37 active markets being incentivized, although there is significant overlap.

Kalshi's market maker documentation explicitly mentions well-known benefits "including but not limited to economic benefits, fee waivers, different position limits, and enhanced access," but whether certain market makers receive more favorable treatment than others is another matter.

Fortunately, we can more easily understand what Polymarket is doing.

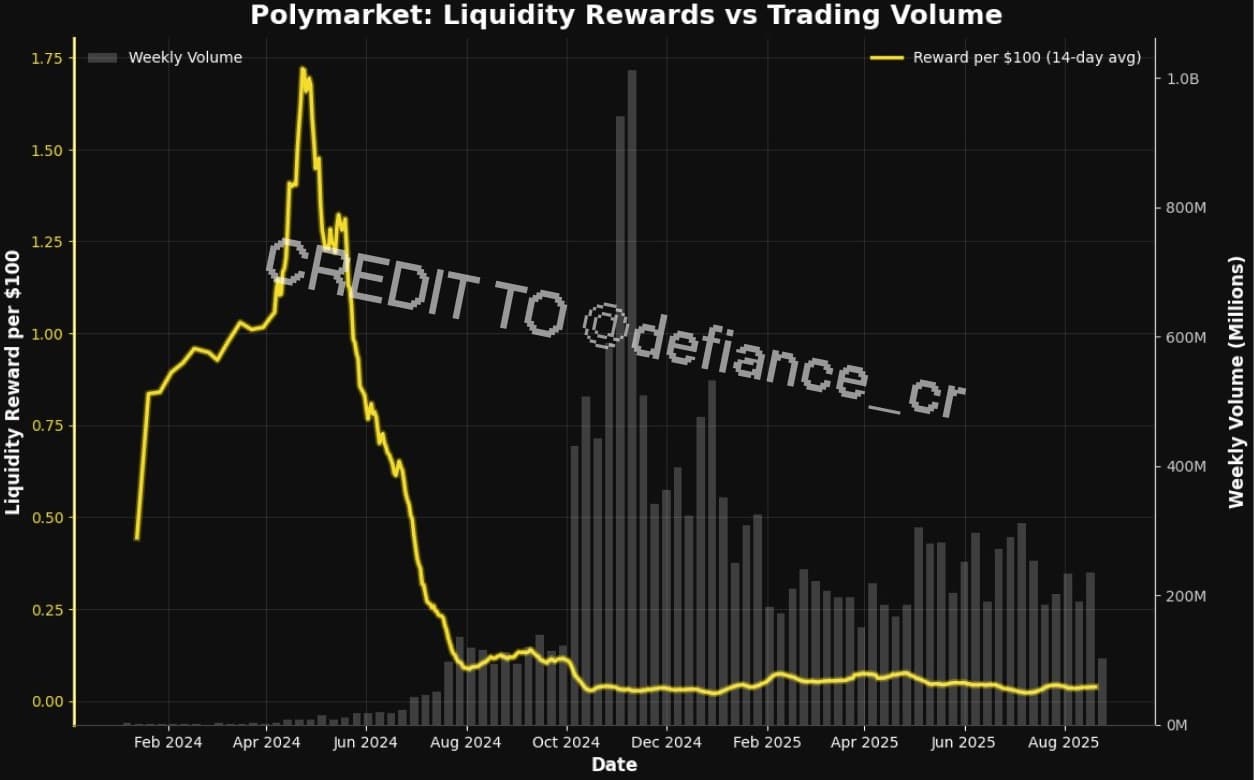

At the beginning of 2024, there was a brief period when Polymarket paid its market makers rewards of up to $1.70 for every $100 in trading volume (source @defiance_cr), before reverting to a more reasonable $0.025 per $100. It is reasonable to assume that this significantly boosted the platform's trading volume, as everyone likes extra income, but in reality, it did not help their trading volume growth much, as shown in the chart below:

The chart shows that after Polymarket adjusted the rewards back to $0.025 per $100 in trading volume, its trading volume actually saw significant growth, indicating that liquidity providers were relatively indifferent or may not have noticed the substantial increase in previous earnings.

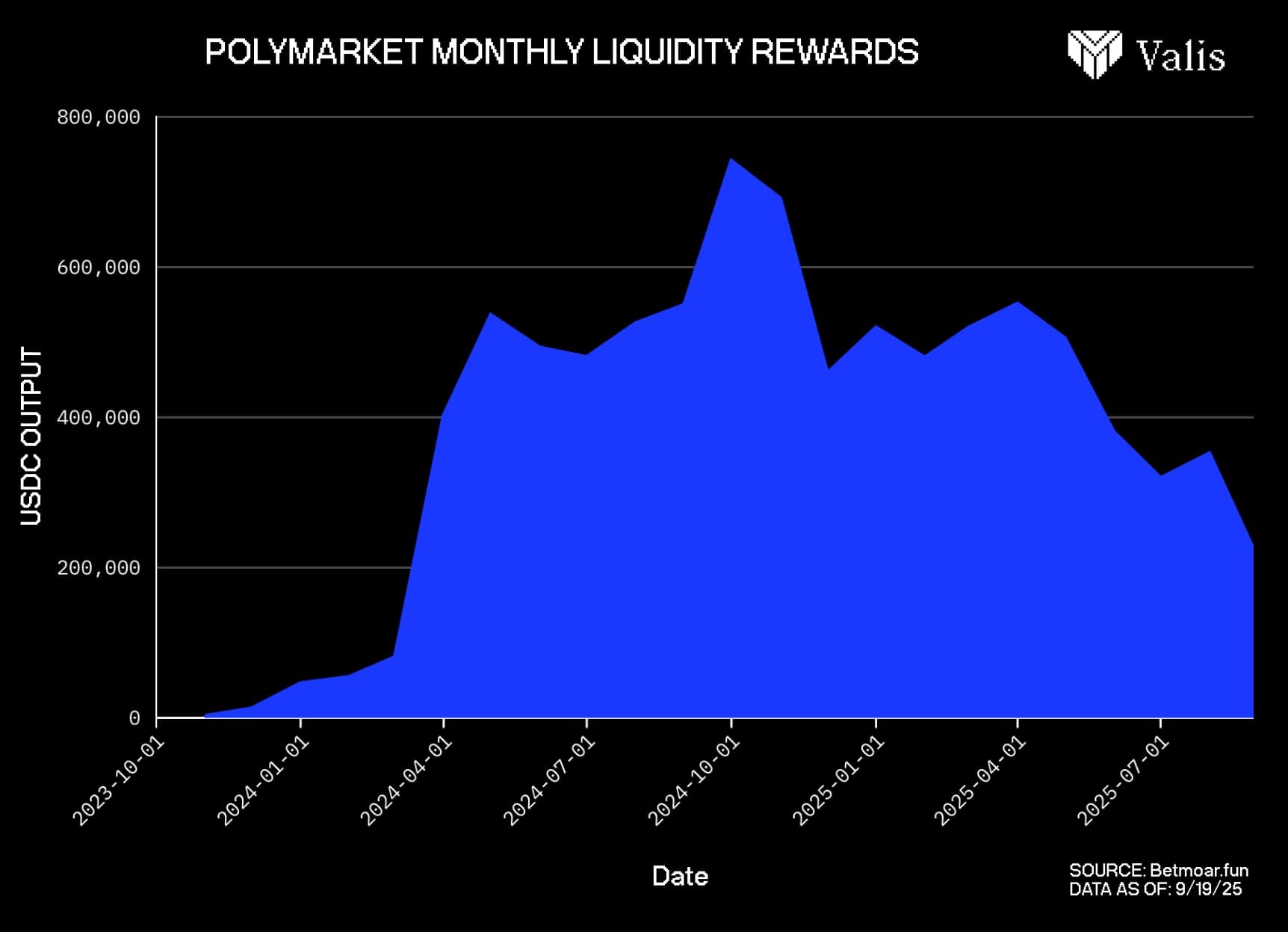

According to data from betmoar.fun, Polymarket has paid nearly $10 million in liquidity rewards since its inception. While we have made it clear that Kalshi's data is opaque, it can be assumed that their payout amounts are similar. It is important to remember that when we say $10 million has been paid, this is entirely in the form of USDC (or other dollar-backed stablecoins) and not token rewards, as neither platform has issued tokens yet.

Adjacent's Lucas has a brief analysis discussing the potential benefits if Polymarket were to issue tokens, and we will leave this brief discussion for later, but it is worth mentioning that issuing tokens would significantly change the competitive landscape between them and Kalshi.

Regarding Kalshi—we cannot conclude that this is conclusive or definitively happening—its underlying reward distribution mechanism may remain unchanged or only slightly increased, but more importantly, it may include a more favorable set of conditions for market makers, particularly third-party or external trading partners like SIG.

In contrast, the liquidity issues are more profound, concerning whether more institutional market makers can be quickly introduced.

Directly quoting the definition from Wikipedia: "Adverse selection is a market situation where information asymmetry leads one party to profit from undisclosed information in a contract or transaction."

Why should we care about adverse selection?

If you are a U.S. citizen looking to trade in prediction markets and are unsure whether to use Polymarket or Kalshi, you can rest assured that this question has an answer. As of the writing of this article, the only way to use Polymarket in the U.S. is to circumvent jurisdictional restrictions and use a VPN, leaving you with Kalshi as your only option.

This is not by design; Polymarket did not voluntarily decide to withhold its product from over 300 million Americans, but rather because Polymarket has yet to gain favor with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, despite their active efforts.

Kalshi obtained its status as a designated contract market in 2020 and won a federal court ruling allowing it to offer event contracts in the U.S. While regulatory and legal terminology may be dry, it plays a significant role in many other topics discussed, especially in market making.

Due to its current legal status, Polymarket has been unable to contract or reach agreements with external/third-party market makers like Kalshi has: most notably, their collaboration with SIG, which was made public last April.

Additionally, Polymarket has also been unable to effectively clear any potential insider trading and adverse selection within its markets, whereas theoretically, Kalshi can do so given its KYC requirements. Due to these barriers, Polymarket has not engaged in market promotion like Kalshi, meaning they cannot fend off "toxic order flow," which also hinders the critical process of attracting more mature market makers (those who may be unwilling to trade in an environment where "toxic order flow" is a possibility).

The main conclusion of this section is that the general statement "market making for prediction markets is bad" may be true, but few consider it a direct concern for the growth of these platforms. Despite the obvious challenges, it is precisely these irregularities and peculiarities of prediction markets that have propelled them to their current status, indicating that addressing these issues as a third party or directly within organizations like Polymarket and Kalshi may hold significant value.

Questions on Combination Betting and Leverage

Discussing the complexities of liquidity and market making is crucial because without this foundation, we cannot argue for the feasibility of combination betting and leverage. Yes, given the current liquidity constraints, it is indeed very difficult to address these issues on a large scale.

Combination betting is very popular and has quickly become a major revenue source for traditional sports betting platforms. Quarterly earnings reports do not explicitly show what percentage of FanDuel or DraftKings' revenue comes from combination betting, but a blog from the PGA Tour in 2023 claims that combination betting accounts for nearly 70% of NFL and NBA bets placed on FanDuel.

Rumors suggest that almost everyone prefers the payout structure of combination betting and the lottery-like outcomes. There is a small but growing ecosystem of content creators on social media dedicated to providing combination betting advice, specific betting setups, and other information targeted at this type of sports betting user.

Sports betting platforms allow users to easily construct combination bets within the app, providing specialized tools to aggregate different bets into a combination bet containing N options without manually calculating odds. All combination bets are different, and absurd posts containing combinations with more than 10 options are ubiquitous on platforms like Reddit, where the implied probabilities of these bets are essentially ludicrously low.

We have discussed that the user base and outcomes of sports betting and prediction markets are comparable, but the way platforms supporting these two forms of speculation handle them is not the same when considering combination betting.

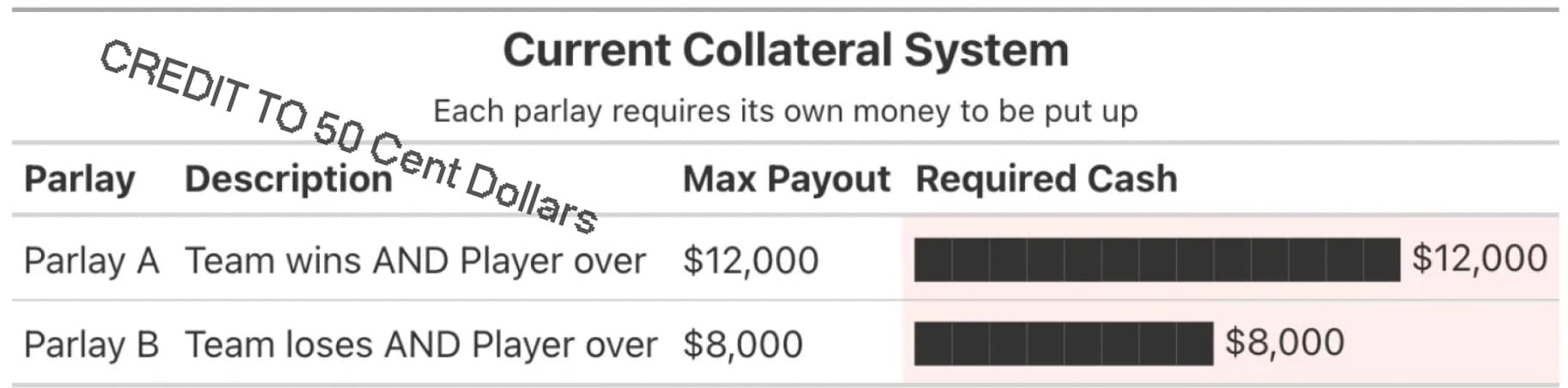

Polymarket and Kalshi must provide full collateral for all positions on their platforms. This means that if the open contracts listed on these two platforms total $150 million, all of that capital is made up of active positions held by platform traders. Sports betting platforms differ in that their users are betting against the house or other market makers who pay out based on the results. This key difference affects the available liquidity on the order book for any specific event market, as the funds must be provided by market makers or users, and these parties must deposit dollars or USDC (in the case of Polymarket) to place bets.

A sports betting platform's daily trading volume can reach billions of dollars, but not all of that capital is real, especially in the case of combination betting. If a user bets $10 on a combination bet with 12 options and odds of +192876, guaranteeing a payout of $19,287, the counterparty market maker does not need to provide that capital immediately. In prediction markets, however, the funds must be in place for settlement, making combination betting quite difficult when considering these long-tail outcomes.

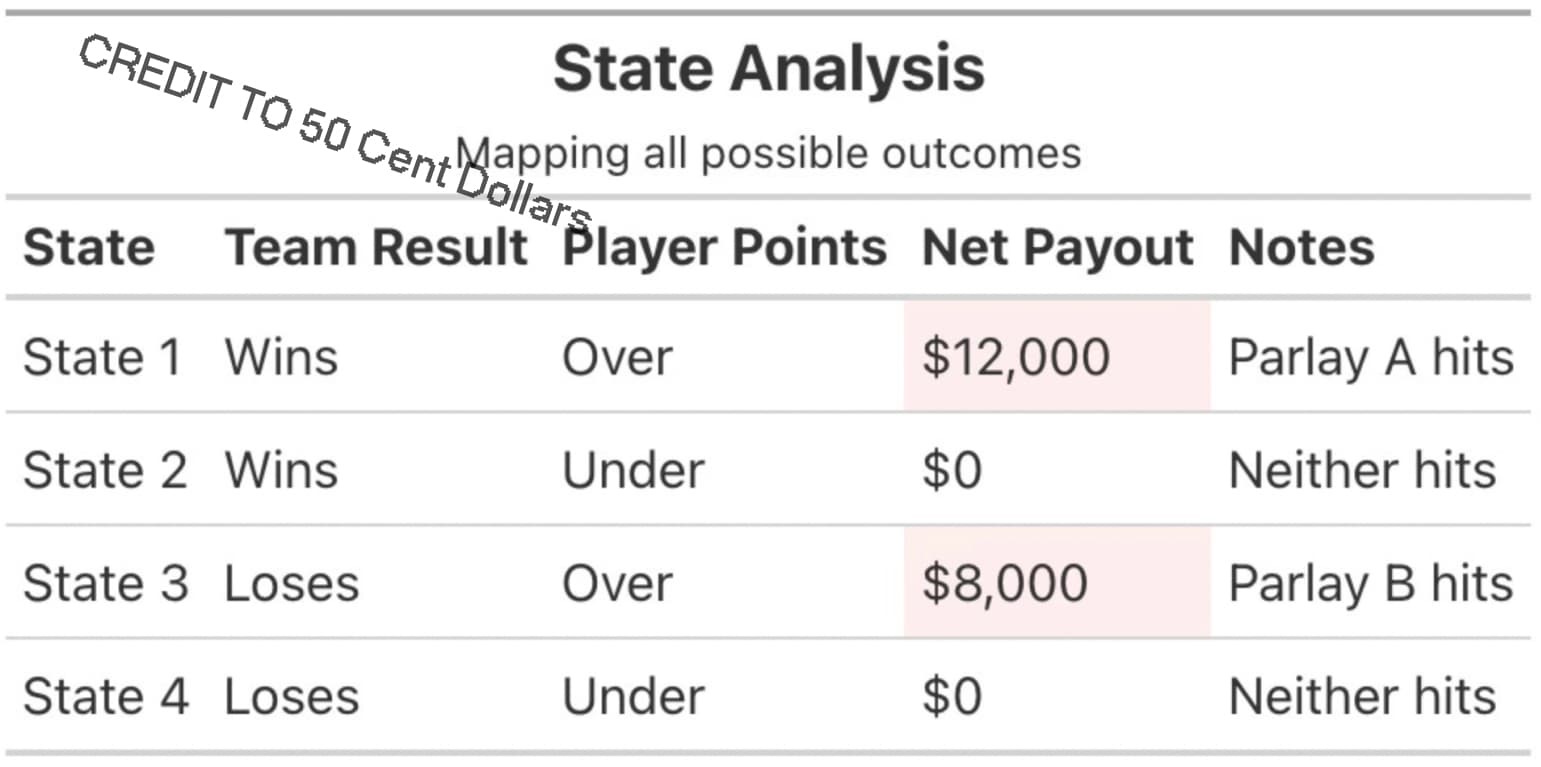

Adhi Rajaprabhakaran provides relevant data here based on a basic hypothetical calculation assuming the usage of prediction market platforms is on par with traditional sports betting:

"When a user bets $S at +X odds, the counterparty must have $S × (X/100) in cash at risk. Therefore, betting $5 at +100,000 odds would lock in ~5,000 dollars, as you could buy ~5000 shares of YES (at $0.1 each). If this is done frequently, these numbers become unattractive. If you accept 2 million tickets with realistic odds combinations in a day, the total cash that market makers need to put up would be hundreds of millions of dollars—if the long-tail effect becomes larger, it would require billions of dollars."

The key conclusion is that "a slight tilt towards high-odds options will cause a surge in collateral demand," making it nearly impossible for existing market makers to meet even a small demand for combination betting. Should they take on 5-10% of the traditional combination betting demand, it would cause a spike in capital requirements for market makers, and considering the previously discussed challenges related to prediction markets—adverse selection, volatility, and inventory risk—this becomes an unnecessary burden for them.

If a cash-collateralized prediction market platform wants to offer combination betting, Adhi lists three possible steps, but each step still represents a version that is much simplified compared to sports betting combination betting:

Strictly limit the betting amounts on high-odds options

Guide users to a preset combination betting menu with at least a minimum amount

Obtain permission for a margin portfolio instead of prepaying for the worst-case payouts for each bet

Regardless of the direction taken, the end result is still a combination betting experience that is significantly less appealing compared to the "self-selection" model of sports betting, and it will lack the typical lottery-style combination betting outcomes that users desire. Kalshi has previously done combination betting, but only for specific or pre-approved markets, and to our knowledge, Polymarket has not explored any form of combination betting. Kalshi's attempts at combination betting so far can be categorized as the second type, which is preset combination betting designated for users seeking more risk, but it is far from traditional sports combination betting.

One interesting aspect of Polymarket's on-chain layout is that third parties could potentially provide this infrastructure themselves, essentially creating a platform that allows users to trade and build combination bets through on-chain Polymarket contracts while managing their own risks. It is currently unclear how the CFTC would view this approach, as its existence would align more with the origins of the DeFi industry rather than anything that exists today. Polymarket may not directly endorse this practice in any case, but it is hard to imagine they wouldn't at least consider the idea.

Kalshi cannot do this; if a third party attempted the above example, it would resemble an over-the-counter business rather than another DeFi protocol, making it less likely to gain attention and fraught with other regulatory risks.

This discussion reveals the flaws in the current collateral system of prediction markets: market makers must provide funds equivalent to the worst-case outcomes, ignoring the obvious fact that two different outcomes are mutually exclusive, and you do not need to over-insure against a scenario that is statistically (and logically) impossible.

From this perspective, observing the full collateral nature of prediction markets shows that it is far less reasonable than it initially appears. The current state of market making means that if a five-option combination bet is created across five independent markets on a platform, even if a fearless speculator bets only $15, the market maker must provide coverage for the worst-case scenario where the trader could win at +4528 odds.

If market makers are forced to stack all their capital to cope with highly improbable events rather than using it for prediction markets that can provide higher capital efficiency independent of combination betting, then the incentives are fundamentally inconsistent. As long as this full collateral requirement exists, it is hard to imagine that combination betting will be rolled out anytime soon, which makes us skeptical about their direct role in the competitive dynamics between these two platforms.

While combination betting may be the primary method for increasing payouts in the sports betting world, leverage is the simplest way in the cryptocurrency space.

We previously showcased the futures trading volume charts of top cryptocurrency exchanges, with monthly totals reaching trillions of dollars. Perpetual futures are popular due to their leverage range, although the specific multiples ultimately depend on the relative liquidity of the exchange and the asset. Assets like BTC, ETH, or SOL may offer leverage of up to 100 times, while tokens with lower liquidity may only provide 3-5 times leverage. This is significant, but it also brings enormous risks, even for experienced traders.

Implementing leveraged prediction markets will be tricky and arguably more complex than the combination betting structures discussed earlier. This relies on prior knowledge of market makers' risk preferences and the challenging role of managing inventory risk, considering that one side of the market is destined to go to zero when the outcome is determined. Market making in leveraged prediction markets will amplify these difficulties, which, while great for speculative users, represents a completely unknown territory for any existing counterparties.

Neither Polymarket nor Kalshi has explored leverage yet, most likely because these platforms are still addressing the challenges of spot market making, but it may also be due to the extremely high annual volatility of prediction markets.

Volatility is just one factor to consider; the inherent structure of binary prediction markets causes liquidity to gradually dissipate from one side of the order book as the outcome approaches certainty. A post by John Wang regarding perpetual contracts on Hyperliquid listed potential solutions such as liquidation bands, pre-expiration leverage decay, oracle rate limits, and pre-settlement auctions.

Some of these solutions are better than others, and we agree that liquidation bands and leverage decay should become the norm for a while in the early stages. This post is good, but there is one flaw I want to point out, particularly regarding scalar markets: "Scalar markets settle within a range, such as CPI percentage or BTC dominance, rather than 0 or 100. This effectively reduces jump risk and supports higher leverage."

Scalar markets are still subject to binary outcomes, even if those outcomes are ranges rather than binary "yes" or "no" options. The issue lies not in how prediction markets are presented, but in how they settle; all these markets settle in the same zero-sum manner. Even though scalar markets may seem different due to their continuity, prices will converge on one side, and jump risk does exist, especially for markets relying on third-party signals.

Over time, it may be possible to introduce safe leverage ratios, but it is unlikely to reach the scale of the cryptocurrency perpetual futures market, let alone markets outside the top 25-30 on these platforms. Keep in mind that while the crypto industry is fascinated by perpetual futures, the leverage issues surrounding Solana memecoins remain unresolved—this is fundamentally a challenging financial engineering problem, and any leveraged product should be handled with extreme caution.

The relevance of leverage and combination betting issues stems from claims that the payouts in prediction markets are not high enough, or that locking up funds for three months or longer in today's market environment is simply a poor risk-reward ratio. While these claims are essentially qualitative, they are absolutely correct and should have been addressed earlier as an obvious issue.

In an industry where a token can emerge with a market cap of $150 million and grow to nearly 15 times that within three days due to billions in trading volume, many prediction market payouts are indeed comparatively weak, but this should not be surprising. The significant role of combination betting in sports betting activities is a relatively recent phenomenon, partly due to previous accessibility issues, but also possibly due to rampant speculation among younger generations.

Regardless of how frequently this sentiment arises, prediction markets cannot compete with the raw excitement present in sports betting, even Kalshi, until these improvements are made.

Forms of Market Manipulation and Historical Accuracy Analysis

Since we will discuss market settlement and the accuracy of these markets before outcomes are determined, it is best to briefly outline how these platforms handle dispute resolution and settlement in their unique ways.

Brief Note on Oracles

For Polymarket, the UMA oracle manages settlement and dispute resolution in a way that can be said to require no human oversight. The UMA protocol is an optimistic oracle and dispute arbitration system that brings a large amount of data on-chain, overseen by a committee of UMA token holders.

Quoting the documentation from Polymarket and UMA: "The UMA Optimistic Oracle allows contracts to quickly request and receive data… The Optimistic Oracle acts as a generalized upgrade game between the contract that initiates the price request and UMA's dispute resolution system (known as the Data Verification Mechanism, DVM)… All contracts built on UMA use the DVM as a backstop for resolving disputes. Disputes submitted to the DVM will be resolved within a few days—determined by a vote from UMA token holders on what the correct outcome should be."

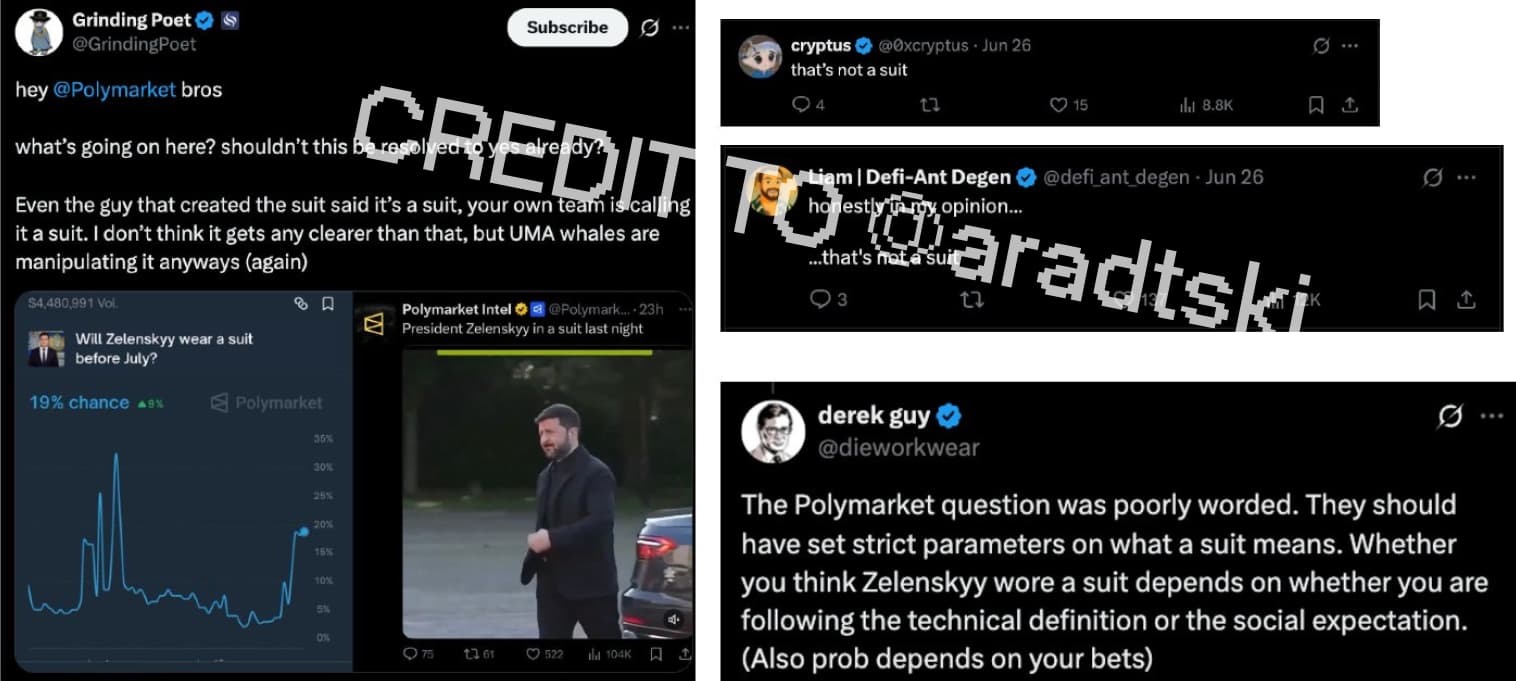

Polymarket's most notorious dispute arose from its market, "Will Zelenskyy wear a suit before July?," which sparked a huge uproar over whether the clothing worn by Zelenskyy could be classified as a suit. This particular market saw over $242 million in trading volume before settling as "no," igniting intense debate across various corners of the X platform, as Zelenskyy appeared to have clearly worn some form of suit.

Polymarket has many other unique examples (@aradtski has listed a good collection), but the Zelenskyy issue stands out particularly because it was a result that everyone could see firsthand.

"The oracle problem is not really an oracle problem because crypto oracles were not originally designed for things like world events," or more simply put, UMA is not suited to manage Polymarket's governance processes in its current state, especially when handling hundreds of millions of dollars each month.

In contrast, Kalshi does not face this issue because they have an internal team responsible for market review and dispute resolution. While this work is slower than a more automated approach with oracles, it likely helps them avoid trouble and negative press. Kalshi utilizes a dedicated market team to handle internal reviews and dispute resolution, but it is worth noting that they may use data sources similar to those of Polymarket, albeit in a slower manner, which may be more resilient to disputes.

Settlement scandals can be seen as a form of manipulation, but ideologically, they are more akin to flaws in platform design. On the other hand, intentional human manipulation can be viewed as a feature and can be achieved through various unique means. Currently, there are not many proposals for improving existing oracles or significant alternative solutions being developed, but if you are interested in the technical aspects of prediction market infrastructure, this is something to keep an eye on.

Manipulation, Crime, and Some Considerations

We have just discussed the historical accuracy of prediction markets, but it is essential to re-examine this concept from a fresh, non-academic perspective. Whether or not you agree that prediction markets are more accurate than mainstream media, polling data, or other sources of truth is not the point: manipulative behavior is not only measurable but can be said to have become a problem.

We propose two different types of manipulation—social coercion and insider arbitrage—and explain whether large players and traders might contribute to this while providing data to support our viewpoint.

Suppose a senior executive at Universal Music Group wants to gauge public sentiment regarding Drake's new album. Perhaps internal surveys and data suggest that the album will perform well, but they are not certain. They have employees from the hypothetical marketing or data science department create a simple multi-outcome market on Polymarket titled something like "Drake's first-week album sales?" and provide a small amount of liquidity.

The outcome range might include less than 1.5 million, 1.5 million-2 million, 2 million-2.5 million, and greater than 2.5 million. From here, you can reasonably gauge consumer expectations for Drake, not only as an artist but also from an investment perspective. Multi-outcome markets are not just boring traders betting on the success or failure of an album; they aggregate beliefs from numerous market makers and possibly informed fans who vote with their money.

Returning to the issue of prediction market accuracy, it is easy to argue that even a market with insufficient liquidity (or this hypothetical case) can provide more value for opinions than an alternative of a survey of a random group of individuals, which cannot measure their internal views or know if they are telling the truth. Suppose hypothetical markets targeting artists like Taylor Swift, Olivia Rodrigo, or Ed Sheeran made headlines, garnering millions of views on the X platform, potentially creating their own mini-marketing waves in the process.

We assume that the record company executive decides to manipulate the order book to boost first-week sales and create a buzz around Drake's new album, to the extent that anyone who sees it will be compelled to pay attention to the upcoming release.

This would obviously cost the record company money, but in this scenario, it is a decent way to generate discussion and create headlines, something that has not been done by others and may be cheaper than typical corporate marketing campaigns targeting artists of Drake's caliber.

If you are a more astute reader, you might notice a problem with this assumption: if an entity were to purchase a large number of contracts for >2.5 million, wouldn't the natural forces of the market push it back toward some equilibrium and fair value?

This is not only correct but has been tested and proven true, even though this hypothetical case differs significantly from real-world market scales.

In June of this year, an analysis by @apralky (also known as Yung Macro) on X pointed out a flaw in Scott Alexander's argument, particularly regarding the claim that large players skewed Polymarket's valuation of Trump's chances of winning the 2024 U.S. presidential election too high.

Scott wrote that the money-based prediction markets priced Trump's chances of winning far higher than non-money prediction market platforms (like Metaculus), which seemed to be caused by large bets from big players skewing the overview away from "fair value." Scott presented a rebuttal argument and a counter-rebuttal to that argument, but we will only look at the objective facts.

Whether large players have distorted the overview from fair value (Trump's winning probability of 54%) to a higher range of 8-10% (Trump's winning probability of 62-64%), the reality is that this market has not corrected the excessive enthusiasm of large players and returned to the assumed fair value. In fact, data from Yung Macro shows that the gap between money-based and non-money platforms has not reverted to fair value but has widened over time.

If traders believe that a large player is distorting the market, causing it to deviate from reality, the sellers should take advantage of this and gradually lower the price over time, bringing it back to the market price before the large player entered. However, this has not happened, and it is illogical to maintain this claim when the data indicates otherwise. In short, the market has functioned, expressing the beliefs of traders, even when experts disagree.

This phenomenon is most evident in the differences between Polymarket and mainstream media coverage of elections. CNN reported that platforms like Polymarket saw things they failed to perceive. However, it is more likely that Polymarket itself did not "see" any particular information but that the collective mindset of those trading on it expressed their truest beliefs and backed them with dollars.

Aashish Reddy echoed these views, stating: "They will self-correct at the margin because any mispricing will attract those who can profit from correcting it: when prices deviate from reality, the next trader to act is likely to be someone who recognizes the error, and their trades will push the market back to the truth."

Without oversimplifying, we occasionally see this phenomenon in traditional finance, such as when a company reports earnings far exceeding expectations, causing its stock price to surge 20-30% after hours, only to self-correct the next day.

This correction may occur after a period of calm, such as when analysts have more time to digest the entire earnings call, or it may simply happen after market makers and all other interested buyers and sellers reach a consensus on the new fair value of the company, which is usually lower than the peak following its earnings surprise.

Looking at the second form of manipulation—insider arbitrage (or insider trading)—we actually have a good example that has been widely discussed since Camilo reported it on the X platform.

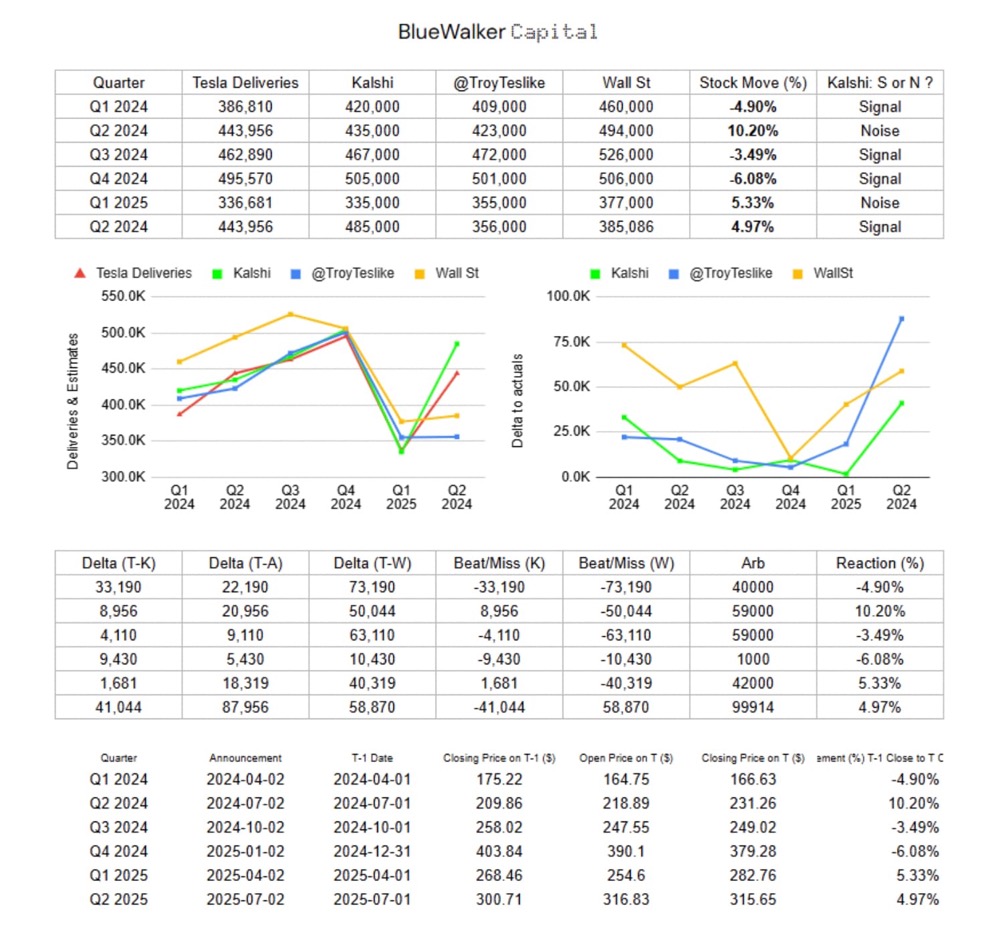

At first glance, Kalshi seems to have predicted Tesla's quarterly delivery numbers more accurately than @TroyTeslike, who specializes in quantitative analysis of Tesla and TSLA, as well as Wall Street predictions.

So, is this an example of collective wisdom surpassing those hired to speculate on such outcomes, or is it another case of large players distorting fair value and causing market imbalance? Or does it represent someone taking advantage of the lax regulatory nature of prediction markets to profit from insider information without facing legal repercussions?