Original Title: No Rivals

Original Author: Mario Gabriele, The Generalist PodcastOriginal Translation: Lenaxin, ChainCatcher

Broadcast Date: July 8, 2025

Summary:

TL&DR

· The essence of success lies in seeking differences

· Founders Fund manages billions of dollars in assets

· He can foresee the chessboard twenty moves ahead and accurately position key pieces

· Talented and unconventional, daring to explore conclusions that most people are afraid to think

· Since the mid-1998 Stanford speech, the three founders of Founders Fund officially met

· Thiel's strength lies in strategy rather than execution

· Pursuing macro investment achievements, systematizing venture capital practices, and simultaneously founding new companies are all different successes—achieved by solving unique problems to gain monopoly status

· All failed companies are the same; they failed to escape competition. "He comes from a hedge fund background and always wants to cash out." Moritz commented on Thiel

ChainCatcher Editor's Summary:

This article is compiled from the podcast No Rivals, presenting how Founders Fund transformed from a small side project into one of Silicon Valley's most influential and controversial companies. It deeply analyzes Peter Thiel's venture capital empire, including the origin story, how Peter Thiel assembled an extraordinary team of investors, how the fund's concentrated bets on SpaceX and Facebook yielded astonishing returns, and how Peter Thiel's contrarian philosophy reshaped the venture capital industry and American politics.

This report is based on exclusive performance data and interviews with key figures obtained from The Generalist Podcast, revealing how the institution set the record for the best returns in venture capital history. The podcast consists of four parts, and this is the first part.

The Prophet

Peter Thiel is nowhere to be seen.

On January 20, to escape the harsh winter storm, the most powerful figures in America gathered under the dome of the Capitol to celebrate Donald J. Trump’s inauguration as the 47th president.

If you have even a fleeting interest in technology and venture capital, it’s hard not to think of Thiel when looking back at the photos from this event. He was absent yet omnipresent.

His former employee (now the Vice President of the United States); a few steps away stands his old partner from The Stanford Review (the new AI and cryptocurrency affairs director of the Trump administration); sitting a bit further away is his earliest angel investment (the founder and CEO of Meta); beside him is his partner, both friend and foe: Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX, and the world’s richest person.

To say that all of this was orchestrated by Peter Thiel would be an exaggeration, but this former chess prodigy’s career has consistently displayed remarkable talent: he can foresee the chessboard twenty moves ahead and accurately position key pieces: moving JD to B4, pushing Sacks to F3, placing Zuck at A7, positioning Elon Musk at G2, and guarding Trump at E8.

He navigates the core centers of power, including the financial sector in New York, the tech scene in Silicon Valley, and the military-industrial complex in Washington; his actions are always cautious and unconventional, making him hard to pin down; he often mysteriously disappears for months, only to suddenly reappear with a sharp quip, a perplexing new investment, or an engaging act of revenge. At first glance, these actions may seem like missteps, but over time, they gradually reveal his extraordinary foresight.

Founders Fund is the core of Thiel's power, influence, and wealth. Since its establishment in 2005, it has grown from a $50 million fund with an immature team into a Silicon Valley giant managing billions of dollars in assets, boasting a top-tier investment team. Its image is controversial, akin to the "bad boy" brigade of the early 1990s.

Performance data supports Founders Fund's flamboyant style. Despite the fund's continued expansion, its concentrated bets on SpaceX, Bitcoin, Palantir, Anduril, Stripe, Facebook, and Airbnb have consistently generated astonishing returns. The 2007, 2010, and 2011 funds achieved the best performance trilogy in venture capital history: with principal amounts of $227 million, $250 million, and $625 million, they realized total returns of 26.5 times, 15.2 times, and 15 times, respectively.

Contemporaries have described Talleyrand's smile as "narcotic," and even the accustomed salon hostess Madame de Staël exclaimed, "If his conversation could be bought, I would go bankrupt."

Peter Thiel seems to possess a similar charm. This is often evident when tracing the origins of Founders Fund. Encounters with Peter Thiel often leave listeners enchanted: some have relocated cities for him, while others have given up prestigious positions just to immerse themselves in his "strange" thoughts.

Whether on the stage of a conference or in a rare podcast, listening to Thiel speak, you will find that his charm does not stem from a diplomat's smooth talk. Instead, his allure comes from a versatile ability to dance through various topics, articulating them with the profound knowledge of a Trinity College professor.

Who else can weave together Lucretius, Fermat's theorem, and Ted Kaczynski to write a classic on startups, argue for the virtues of monopoly, and share the wisdom of running a business like a cult? How many people's thoughts encompass such rigor and non-religiosity?

Ken Howery and Luke Nosek had already succumbed to this charm years before co-founding Founders Fund with Peter Thiel in 2004. Ken Howery's "conversion moment" occurred during his undergraduate studies in economics at Stanford. In Peter Thiel's 2014 published business philosophy book, Zero to One, he described Howery as "the only member of the PayPal founders who fits the stereotype of a privileged American childhood, the only Eagle Scout in the company." This Texan youth moved to California in 1994 and began writing for The Stanford Review, a conservative student publication co-founded by Peter Thiel seven years earlier.

Peter Thiel's first encounter with Ken Howery stemmed from a Stanford Review alumni event. As Howery was promoted to senior editor, the two kept in touch. On the eve of this Texan's graduation, Thiel extended an olive branch: would he like to be the first employee of his new hedge fund? He suggested they discuss it in detail at the Palo Alto steakhouse, Sundance.

Howery quickly realized this was no ordinary recruitment dinner. During a four-hour intellectual odyssey, the young Thiel displayed complete charm. "From political philosophy to entrepreneurial ideas, his insights on every topic were more captivating than anyone I encountered during my four years at Stanford, and the breadth and depth of his knowledge were astonishing," Howery recalled.

Although he made no commitments on the spot, upon returning to campus that night, Howery confided to his girlfriend, "I might work with this person for the rest of my life."

The only obstacle was Howery's original plan to join ING Barings in New York for a high-paying position. In the following weeks, he asked friends and family whether to choose the lucrative investment bank or follow a new investor managing less than $4 million. "Everyone 100% advised me to choose the bank, but after thinking for weeks, I decided to go the other way," Howery stated.

Before graduation, while auditing his new boss's campus lecture, a young man with brown curls, Luke Nosek, suddenly leaned over and asked, "Are you Peter Thiel?"

"No, but I'm about to work for him," Howery replied, as the young man, identifying himself as Luke Nosek, handed him a business card that simply read "Entrepreneur." "The company I founded," Nosek explained. At that time, Nosek was developing Smart Calendar, one of the many electronic scheduling applications that emerged around the same period, which Thiel had invested in.

This interaction raised a puzzling question: how could Nosek forget his supporter, someone he had shared breakfast with several times? Perhaps it had been a long time since they last met, or maybe this quirky and driven founder simply did not care about the investor's appearance. Or perhaps Thiel had just been momentarily forgotten.

In Nosek, Thiel found the ideal talent prototype: talented and unconventional, daring to explore conclusions that most people are afraid to think. This powerful mind, free thought, and disregard for social norms perfectly aligned with Thiel's values. Thiel soon followed Nosek's lead and signed with the human cryopreservation organization Alcor.

Since the mid-1998 Stanford speech, the three founders of Founders Fund officially met. Although the three spent another seven years establishing their respective venture capital funds, deeper collaboration had already begun immediately.

Spite Store

"I am Larry David, and I want to introduce you to the soon-to-open Latte Larry's coffee shop." In the opening line of the nineteenth episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, the creator of Seinfeld said, "Why get involved with coffee? Because the owner of the shop next door is such a jerk, I had to do something, so I opened a spite store for myself."

Thus, the cultural term "spite store" was born—business retaliation through customer competition.

To some extent, Founders Fund is Peter Thiel's "Spite Store." While the acerbic Mocha Joe inspired Larry David, Thiel's actions can be seen as a response to Sequoia Capital's Michael Moritz. Moritz, a journalist turned investor from Oxford, is a legendary figure in venture capital, responsible for early investments in Yahoo, Google, Zappos, LinkedIn, and Stripe.

Moritz is a literary-minded investment expert who has repeatedly become a stumbling block in Thiel's early entrepreneurial history.

The story begins with PayPal: that summer, Thiel met the Ukrainian-born entrepreneurial genius Max Levchin. He graduated from the University of Illinois, where he developed a highly profitable encryption product for PalmPilot users. After hearing the pitch, Thiel said, "That's a good idea; I want to invest."

Thiel immediately decided to invest $240,000. This underestimated decision ultimately yielded a return of $60 million and marked the beginning of one of the most tumultuous entrepreneurial epics of the internet era. (The book "Founders" provides a comprehensive account of this.)

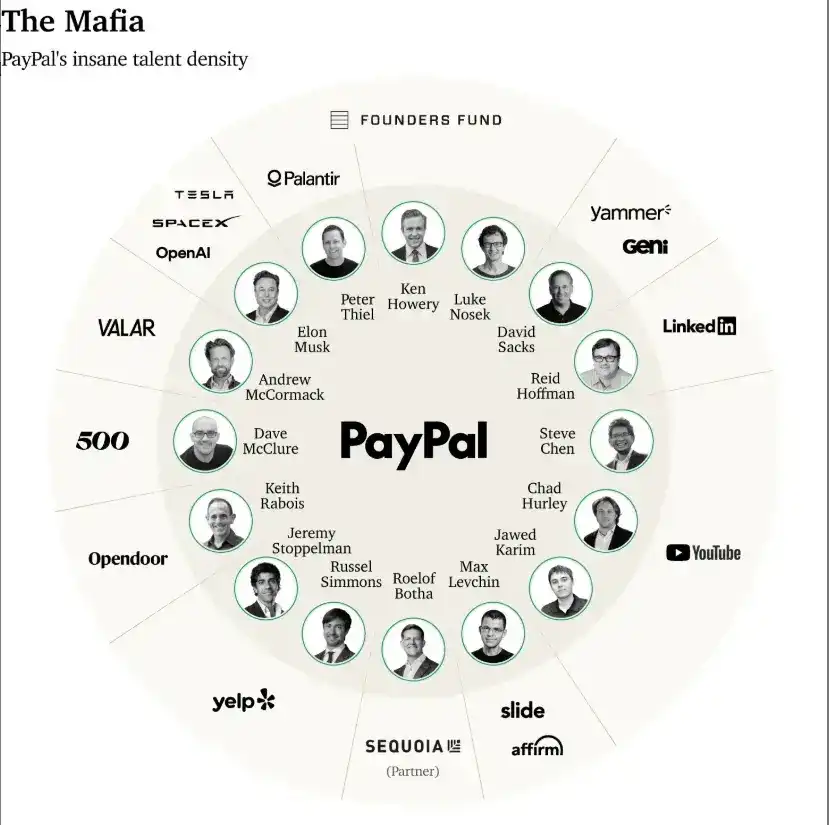

Levchin quickly recruited the failed entrepreneur Nosek. Soon after, Thiel and Howery joined full-time, with Thiel serving as CEO. The addition of talents like Reid Hoffman, Keith Raboy, and David Sachs created one of the most luxurious entrepreneurial lineups in Silicon Valley history.

The company, originally named Fieldlink (later renamed Confinity), soon crossed paths with X.com, founded by Elon Musk. To avoid a war of attrition, the two companies chose to merge, naming the new company "PayPal," derived from Confinity's most popular email address and payment connection.

This merger required not only the integration of two stubborn management teams but also the acceptance of each other's investments and investors.

Moritz, who had invested in X.com, suddenly had to deal with a group of eccentric geniuses. On March 30, 2000, the two companies announced they had secured $100 million in Series C funding—this round was pushed by Thiel, as he anticipated a downturn in the macro economy. His foresight proved correct: within days, the internet bubble burst, and many star companies collapsed.

"I want to thank Peter," one employee said, "he made the judgment and insisted that we must complete the funding because the end was near…"

However, his keen macro interpretation was not enough to save the company. Thiel saw an opportunity for profit. At a 2000 PayPal investor meeting, Thiel suggested: if the market really fell further as he expected, why not short it? PayPal could simply transfer its newly acquired $100 million to Thiel Capital International, and he would take care of the rest.

Moritz was furious, saying, "Peter, it's simple," a board member recalled Moritz's warning, "if the board passes this proposal, I will resign immediately." Thiel found it hard to understand this obstinate reaction; the fundamental disagreement lay in Moritz's desire to do the right thing, while Thiel wanted to be the right person. Finding common ground between these two epistemological extremes was not easy.

In the end, both sides suffered: Moritz successfully blocked Thiel's plan, but Thiel's prediction was entirely correct. After the market crash, one investor admitted, "If we had shorted at that time, the profits would have exceeded all of PayPal's operating income."

This boardroom conflict intensified the distrust between the two, and a power struggle months later led to a complete rupture. In September 2000, under the leadership of Levchin, Thiel, and Scott Bannister, PayPal employees staged a coup to overthrow CEO Elon Musk (who had just been ousted from the parachuted CEO Bill Harris). Musk refused to compromise, and Thiel's rebellious faction had to persuade Moritz to approve Thiel taking over the company. Moritz set a condition: Thiel could only serve as interim CEO.

In fact, Thiel had no intention of running PayPal long-term; his strength lay in strategy rather than execution. But Moritz's terms forced him to humbly seek a successor for himself. It wasn't until an external candidate also expressed support for Thiel to officially become CEO that Moritz changed his mind.

This power game of "first belittling and then praising" deeply wounded this vengeful genius, laying the groundwork for his later establishment of Founders Fund.

Despite the internal conflicts at PayPal, the company ultimately succeeded. And Thiel had to admit that Moritz played a crucial role in this. When eBay made a $300 million acquisition offer in 2001, Thiel advocated for acceptance, while Moritz insisted on independent development.

"He comes from a hedge fund background and always wants to cash out," Moritz later commented on Thiel. Fortunately, Moritz convinced Levchin, and PayPal rejected the acquisition. Soon after, eBay raised its offer to $1.5 billion, five times the exit price Thiel had initially suggested.

This deal made Thiel and his "gang" members very wealthy, adding another brilliant achievement to Moritz's investment record. If the two had different personalities, perhaps time could have eased the hostility, but the reality was that this was just the beginning of a prolonged war.

Clarium Call

As evidenced by the rejected $100 million macro bet, Thiel never extinguished his passion for investing. Even during his time at PayPal, he and Howery continued to manage Thiel Capital International. "We spent countless nights and weekends keeping the fund running," Howery revealed.

To align with Thiel's broad interests, they pieced together a mixed investment portfolio of stocks, bonds, foreign exchange, and early-stage startups. "We completed 2-3 deals annually," Howery specifically pointed out the investment in the email security company Ironport Systems in 2002—this company was acquired by Cisco for $830 million in 2007.

The $60 million profit from the PayPal acquisition further fueled Thiel's investment ambitions. Even during the period of scaling up management, he pursued multiple paths: chasing macro investment achievements, systematizing venture capital practices, and simultaneously founding new companies. Clarium Capital became the core vehicle for these ambitions.

In the same year the PayPal acquisition was completed, Thiel set out to establish the macro hedge fund Clarium Capital. "We are striving for a systematic worldview, as proclaimed by people like Soros," he explained in a 2007 Bloomberg profile interview.

This perfectly aligned with Thiel's cognitive traits—he has a natural talent for grasping civilization-level trends and an instinctive resistance to mainstream consensus. This way of thinking quickly demonstrated its power in the market: Clarium's assets under management skyrocketed from $10 million to $1.1 billion within three years. In 2003, it profited 65.6% by shorting the dollar, and after a sluggish 2004, it achieved a 57.1% return in 2005.

Meanwhile, Thiel and Howery began planning to systematize their scattered angel investments into a professional venture capital fund. Their performance gave them confidence: "When we looked at the portfolio, we found internal rates of return as high as 60%-70%," Howery stated, "and that was just from part-time, casual investments. What if we operated systematically?"

After two years of preparation, in 2004, Howery launched fundraising for a fund initially sized at $50 million, originally intended to be named Clarium Ventures. They invited Luke Nosek to join as a part-time member, as usual.

Compared to the billions managed in hedge funds, $50 million seemed insignificant, but even with the halo of the PayPal founding team, fundraising was still exceptionally difficult. "It was much harder than expected; everyone has a venture capital fund now, but at that time, it was very alternative," Howery recalled.

Institutional LPs showed little interest in such a small fund. Howery had hoped that Stanford University's endowment fund would serve as an anchor investor, but they withdrew due to the fund's small size. Ultimately, they raised only $12 million in external funding—mainly from personal investments by former colleagues.

Eager to get started, Thiel decided to personally contribute $38 million (76% of the initial fund) to fill the gap. "The basic division of labor was Peter providing the money, and I providing the effort," Howery recalled. Given Thiel's other commitments, this division of labor was inevitable.

The 2004 Clarium Ventures (later renamed Founders Fund) inadvertently became the best-positioned fund in Silicon Valley, thanks to two personal investments Thiel completed before fundraising. The first was Palantir, co-founded in 2003—Thiel again took on dual roles as founder and investor, launching the project with PayPal engineer Nathan Gettings and Clarium Capital employees Joe Lunsdale and Stephen Cohen. The following year, he invited his Stanford Law School classmate, the unconventional curly-haired genius Alex Karp, to serve as CEO.

Palantir's mission was highly provocative: drawing on the imagery of the "seeing stone" from The Lord of the Rings, it aimed to use PayPal's anti-fraud technology to help users achieve cross-domain data insights. But unlike conventional enterprise services, Thiel targeted the U.S. government and its allies as clients. "After 9/11, I thought about how to combat terrorism while safeguarding civil liberties," he explained to Forbes in 2013. This government-oriented business model also faced financing difficulties—investors were skeptical about the slow government procurement process.

Kleiner Perkins executives directly interrupted Alex Karp's roadshow, arguing that the business model was unfeasible; old rival Mike Moritz, while arranging a meeting, doodled disinterestedly throughout the entire session—this seemed to be yet another deliberate slight against Thiel. Although they failed to impress the Sand Hill Road venture capital firm, Palantir gained favor with the CIA's investment arm, In-Q-Tel. "What impressed me most about this team was their focus on human-machine data interaction," a former executive commented. In-Q-Tel became Palantir's first external investor with a $2 million investment, which later brought Thiel significant financial and reputational returns. Founders Fund subsequently invested a total of $165 million, and by December 2024, the value of its holdings reached $3.05 billion, yielding a return of 18.5 times.

But the substantial returns would take time, and Thiel's second key investment before founding Clarium Ventures paid off more quickly: in the summer of 2004, Reid Hoffman introduced the 19-year-old Mark Zuckerberg to his old friend Thiel. These two PayPal comrades, who had differing political views yet mutual respect, had already engaged in deep discussions about social networks. By the time they met Zuckerberg in Clarium Capital's luxurious San Francisco Presidio office, they had a mature understanding and investment determination.

"We did thorough research in the social networking field," Thiel admitted at a Wired event, "the investment decision was unrelated to the meeting performance—we had already made up our minds to invest." The 19-year-old, dressed in a T-shirt and Adidas sandals, exhibited the "Asperger's-style social awkwardness" that Thiel admired in "Zero to One": he neither tried to please nor was ashamed to ask unfamiliar financial terms. This quality of stepping away from imitative competition was precisely the entrepreneurial advantage in Thiel's eyes.

Days after the meeting, Thiel agreed to invest $500,000 in Facebook in the form of convertible debt. The terms were straightforward: if users reached 1.5 million by December 2004, the debt would convert into equity, granting a 10.2% stake; otherwise, he had the right to withdraw the funds. Although the target was not met, Thiel still chose to convert the debt into equity—this conservative decision ultimately yielded over $1 billion in personal profit. Although Founders Fund did not participate in the first round of investment, it later invested a total of $8 million, ultimately generating $365 million in returns for LPs (46.6 times).

Thiel later viewed the Series B financing of Facebook as a significant mistake. The first round investment was valued at $5 million, and eight months later, Zuckerberg informed him that the Series B valuation had reached $85 million. "The graffiti on the office walls was still terrible, the team had only eight or nine people, and every day felt unchanged," Thiel recalled. This cognitive bias led him to miss the opportunity to lead the investment, only doubling down when the Series C valuation reached $525 million. This taught him an intuitive lesson: "When smart investors lead a valuation surge, it is often still underestimated—people always underestimate the acceleration of change."

Sean Parker's decision to blacklist Michael Moritz had its reasons. The son of a television advertising broker and an oceanographer, Parker shocked the tech world at the age of 19 with the P2P music-sharing application Napster. Although Napster was ultimately shut down in 2002, it earned Parker both reputation and controversy. That same year, he founded the contact management application Plaxo, whose social features and "dangerous prodigy" aura attracted investors like Moritz from Sequoia Capital, who invested $20 million.

Plaxo repeated the fate of Napster: it started strong but declined. Reports at the time indicated that Parker's management style was erratic—disorganized schedules, a distracted team, and volatile emotions. By 2004, Moritz and angel investor Ram Sriram decided to remove Parker. When Parker attempted to cash out his shares and was blocked, tensions escalated: Plaxo's investors hired private detectives to track his whereabouts, discovering signs of drug use in his communications (Parker claimed it was for recreational purposes and did not affect his work). This farce ended with Parker's exit in the summer of 2004 but unexpectedly led to a turning point—after leaving Plaxo, he immediately began collaborating with Mark Zuckerberg. The two had met earlier that year when Facebook rapidly took over the Stanford campus, and Parker proactively reached out to the young founder to discuss development.

Parker even flew to New York to have dinner with Zuckerberg at a trendy Tribeca restaurant, even overdrawing his bank account. As Plaxo fell apart, he reunited with Zuckerberg in Palo Alto and soon became Facebook's president, initiating a brief yet legendary collaboration. His first move was to take revenge on Michael Moritz and Sequoia Capital—when Facebook's user count surpassed one million in November 2004, Sequoia sought to engage. Parker and Zuckerberg devised a cruel prank: they deliberately arrived late in pajamas, presenting a slideshow titled "Top Ten Reasons Not to Invest in Wirehog," mocking Sequoia with slides that included "We have no revenue," "We arrived late in pajamas," and "Sean Parker is involved." "Given their actions, we could never accept Sequoia's investment," Parker stated. This missed opportunity may have become one of Sequoia's most painful losses in history.

As this episode illustrates, the Napster founder played a key role in early Facebook financing, guiding Zuckerberg into the world of venture capital. Therefore, when Zuckerberg met Thiel and Hoffman in Clarion's Presidio office, Parker was also present.

Although Thiel and Parker had crossed paths during their early days at Plaxo, the real foundation for their collaboration was laid during the Facebook era. In August 2005, Parker was arrested while renting a party villa in North Carolina due to the presence of a minor assistant and a cocaine search incident (though he was not charged and denied knowledge), ultimately being forced to leave Facebook. This, however, became a turning point for all parties involved: Zuckerberg was ready to take over management, investors were relieved to be rid of a talented yet elusive spokesperson, and Parker admitted that his "sprint and then disappear" personality was not suited for daily operations.

Months later, Parker joined Thiel's venture capital firm as a general partner—by this time, it had been renamed Founders Fund (eventually dropping the definite article like Facebook). This name better aligned with its ambitions and positioning. "We had some criticisms of certain investors from the PayPal era; we believed we could operate in a completely different way," Howery stated. Its core philosophy was simple yet disruptive: never oust the founders.

This seemed commonplace in today's "founder-friendly" market, but at the time, it was groundbreaking. "They pioneered the 'founder-friendly' concept; the norm in Silicon Valley was to find technical founders, hire professional managers, and ultimately kick both out. Investors were the actual controllers," commented Ryan Peterson, CEO of Flexport.

"This was how the venture capital industry operated for the first 50 years until Founders Fund emerged," summarized John Collison, co-founder of Stripe, regarding the history of venture capital. Since the 1970s, Kleiner Perkins and Sequoia Capital had achieved success through active management involvement, and this "investor-led" model had proven effective in cases like Atari and Tandem Computers. Even 30 years later, top venture capitalists retained this mindset—power belonged to the capital side rather than the entrepreneurs. Sequoia's legendary founder Don Valentine even jokingly suggested that mediocre founders should be "locked in the Manson family's dungeon."

Founders Fund's "founder-centric" philosophy was not only a differentiating strategy but also stemmed from Thiel's unique understanding of history, philosophy, and the essence of progress. He firmly believed in the genius value of "sovereign individuals," arguing that constraining those who break conventions was not only economically foolish but also a civilizational destruction. "These people will destroy the creations of the world's most valuable inventors," Luke Nosek articulated the team's disdain for traditional venture capital.

Sean Parker perfectly embodied this philosophy, but his joining at the age of 27 still raised concerns among investors. Reports announcing his appointment bluntly stated, "His past experiences made some LPs nervous." Parker himself admitted, "I always lack a sense of security; after meetings, I constantly ask myself if I provided value."

This concern drew the ire of old rival Mike Moritz. After raising $50 million in 2004, Founders Fund aimed for $120-150 million in 2006. By this time, the team had undergone a transformation: Parker joined, Nosek came on board full-time, and with Thiel's aura as Facebook's first external investor, this small firm, originally a side project of a hedge fund, was evolving into a rising force.

This move clearly angered Moritz. According to Howery and others, the Sequoia leader attempted to obstruct their fundraising: "During our second fundraise, a warning slide appeared at the Sequoia annual meeting—'Stay Away from Founders Fund.'" Two years later, Brian Singerman, who joined at that time, added details: "They threatened LPs that if they invested in us, they would permanently lose access to Sequoia."

Simultaneous reports indicated that Moritz's wording was more subtle. He emphasized at an LP meeting that he "appreciated founders who stayed committed to their companies for the long term," naming several well-known entrepreneurs who failed to do so. This was clearly a veiled reference to Founders Fund partner Sean Parker. "We increasingly respect those founders who create great companies rather than those who prioritize personal interests over the team," Moritz later wrote in response.

This "boomerang" effect actually propelled Founders Fund forward: "Investors became curious: why was Sequoia so wary? This released a positive signal," Howery stated. In 2006, the fund successfully raised $227 million, with Thiel's contribution ratio dropping from 76% in the first fund to 10%. Howery pointed out, "Stanford University's endowment fund led the investment, marking our first recognition from institutional investors."

As early investments began to show results, Founders Fund's unique investment philosophy started to demonstrate its power. Thiel's aversion to institutionalized management kept the fund in a state of "efficient chaos" during its first two years. Howery was busy scouting projects, while the team refused to adhere to fixed agendas or routine meetings.

Since Thiel had to balance his commitments to Clarium Capital, his time was extremely limited. Howery stated, "I could only arrange for him to participate in key meetings." Although Parker's addition did not change the fundamental operation of the fund, it brought more systematic approaches: Howery explained, "When Luke and Sean joined, the three of us could evaluate projects together, or one person could do an initial screening before bringing it to the team for a decision."

Core team formation with complementary abilities: "Peter is a strategic thinker, focusing on macro trends and valuations; Luke combines creativity with analytical skills; I focus on team evaluation and financial modeling," Howery analyzed. Parker then completed the product dimension: "He has a deep understanding of internet product logic, and his experience at Facebook made him proficient in identifying consumer internet pain points, allowing him to accurately spot opportunities in niche areas." His personal charisma also became a negotiating tool: "He is highly persuasive, especially outstanding during the closing stages of deals."

In addition to the two iconic investments in Facebook and Palantir, Founders Fund also placed a $689 million bet on Buddy Media, which was sold to Salesforce, but missed out on YouTube—this was a project that should have been "within their range," as founders Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Joed Kareem all came from PayPal, and it was ultimately captured by Sequoia's Roelof Botha, who sold it to Google for $1.65 billion just a year later.

Regardless, the performance of Founders Fund in its early years was already impressive, and even more glorious moments were about to come.

In 2008, Thiel reunited with old rival Elon Musk at a friend's wedding. The former PayPal associate had by then used his cash-out funds to establish both Tesla and SpaceX. While the venture capital market was chasing the next consumer internet hotspot, Thiel's interest began to wane—this stemmed from his obsession with the teachings of French philosopher René Girard during his time at Stanford. "Girard's ideas were out of sync with the times, perfectly suited for rebellious undergraduates," Thiel recalled.

Girard proposed the theory of "mimetic desire": human desire originates from imitation rather than intrinsic value. This theory became the core framework for Thiel's understanding of the world. After Facebook's rise, witnessing the venture capital community collectively chase the mimetic frenzy of social products, Founders Fund did invest in the local social network Gowalla (later acquired by Zuckerberg), but it felt forced.

Thiel succinctly summarized in "Zero to One": "All successful companies are different—they achieve monopoly by solving unique problems; all failed companies are the same, failing to escape competition." Although monopolies are hard to come by in the venture capital field, Thiel still implemented this idea in his investment strategy: seeking areas that other investors were unwilling or unable to touch.

Thiel turned his attention to hard tech—companies that build the atomic world rather than the bit world. This strategy came at a cost: after Facebook, Founders Fund missed major opportunities in social domains such as Twitter, Pinterest, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Snap. But as Howery stated, "You would be willing to trade all those misses for SpaceX."

After the wedding reunion in 2008, Thiel proposed investing $5 million in SpaceX, partly motivated by "making up for the rift during the PayPal era," showing that he was not yet fully convinced of Musk's technology. At that time, SpaceX had already experienced three launch failures and was nearly out of funds. An email mistakenly forwarded to Founders Fund by a former investor further exposed the industry's general pessimism towards SpaceX.

Although Parker chose to avoid the unfamiliar field, other partners pushed forward with full force. As the project lead, Nosek advocated for increasing the investment amount to $20 million (nearly 10% of the second fund), entering at a pre-money valuation of $315 million—this was the largest investment in Founders Fund's history and proved to be the wisest decision.

"This was highly controversial; many LPs thought we were crazy," Howery admitted. But the team firmly believed in Musk and the technological potential: "We had missed several projects from our PayPal colleagues; this time we had to go all in." Ultimately, this investment quadrupled the fund's stake in its best project.

A well-known LP that Founders Fund was negotiating with thus severed ties. "We parted ways because of this," Howery revealed. This anonymous LP missed out on astonishing returns—over the next 17 years, the fund cumulatively invested $671 million in SpaceX (second only to Palantir's holdings). By December 2024, when the company conducted an internal share buyback at a valuation of $350 billion, that holding had reached a value of $18.2 billion, achieving a 27.1 times return.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。