Author: Vitalik Buterin

Translator: Karen, Foresight News

In Ethereum, resources were limited until recently and were priced using a single resource called "Gas." Gas is a unit of measurement for the "computational effort" required to process specific transactions or blocks. Gas combines various types of "computational effort," including:

- Raw computation (e.g., ADD, MULTIPLY);

- Reading, writing, and writing to Ethereum storage (e.g., SSTORE, SLOAD, ETH transfer);

- Data bandwidth;

- Cost of generating ZK-SNARK proofs for block production.

For example, the transaction I sent consumed a total of 47,085 Gas. This includes: (i) a base cost of 21,000 Gas, (ii) 1556 Gas consumed by the calldata bytes included as part of the transaction, (iii) 16,500 Gas consumed by reading and writing to storage, (iv) 2149 Gas consumed by generating logs, with the remainder used for EVM execution. The transaction fee that users must pay is directly proportional to the gas consumed by the transaction. A block can contain a maximum of 30 million Gas, and the gas price is continuously adjusted through the EIP-1559 targeting mechanism to ensure that each block contains an average of 15 million Gas.

This approach has a major advantage: because all content is merged into a virtual resource, the market design is very simple. It is easy to optimize transactions to minimize costs, and optimizing blocks to collect the highest possible fees is relatively easy (excluding MEV), and there are no strange incentive mechanisms encouraging some transactions to be bundled with others to save costs.

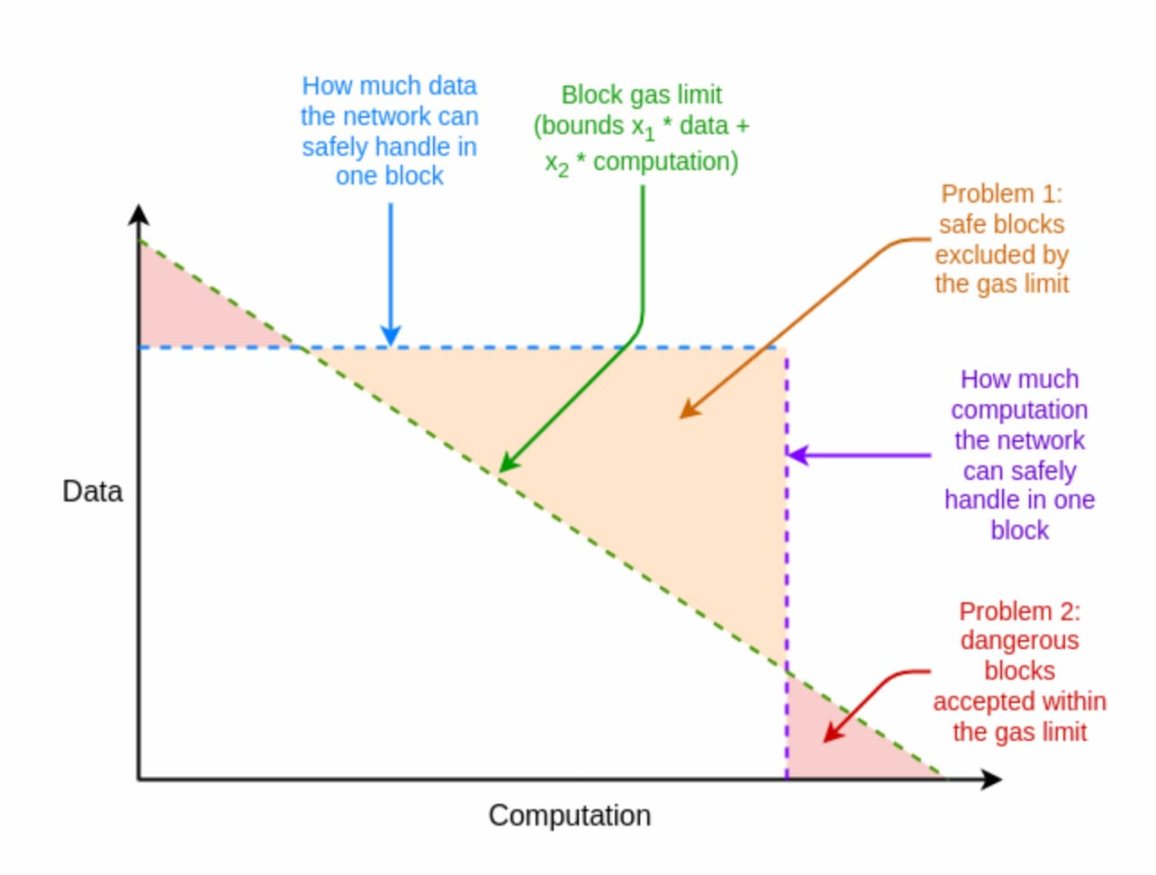

However, this approach also has inefficiencies: it treats different resources as interchangeable, while the actual underlying constraints are not the same. To understand this issue, you can first look at the following chart:

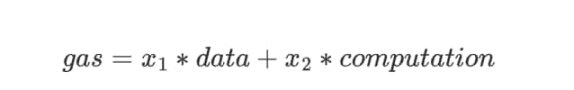

Gas limits impose a constraint:

The actual underlying security constraints are usually closer to:

This difference means that gas limits either arbitrarily exclude actually secure blocks or accept blocks that are actually insecure, or both.

If there are n types of resources with different security constraints, one-dimensional gas may reduce throughput by up to n times. Therefore, people have long been interested in the concept of multi-dimensional gas, and through EIP-4844, we have actually implemented multi-dimensional gas on Ethereum. This article explores the advantages of this approach and the prospects for further enhancement.

Blob: Multi-Dimensional Gas in Dencun

At the beginning of this year, the average block size was 150 kB. A large part of this was Rollup data: Layer2 protocols store data on-chain. This data is very expensive: although the cost of transactions on Rollup is only 5-10 times that of corresponding transactions on Ethereum L1, this cost is still too high for many use cases.

So why not reduce the gas cost of calldata (currently 16 Gas for non-zero bytes and 4 Gas for zero bytes) to make Rollup cheaper? We have done this before, and we can do it again now. But the answer here is: the maximum block size is 30,000,000/16=1,875,000 non-zero bytes, and the network can barely or almost cannot handle blocks of this size. Reducing the cost by 4 times would increase the maximum value to 7.5 MB, which would pose a huge risk to security.

This problem was ultimately solved by introducing a separate, Rollup-friendly data space (called a blob) in each block.

These two resources have different prices and limits: after the Dencun hard fork, an Ethereum block can contain a maximum of (i) 30 million Gas and (ii) 6 blobs, each of which can contain approximately 125 kB of calldata. Both resources have separate prices and are adjusted through a pricing mechanism similar to EIP-1559, with the goal of averaging 15 million Gas and 3 blobs per block.

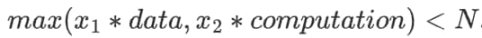

As a result, the cost of Rollup has been reduced by 100 times, the transaction volume on Rollup has increased by more than 3 times, and the theoretical maximum block size has only slightly increased: from about 1.9 MB to about 2.6 MB.

Note: Rollup transaction fees provided by Growthepie.xyz. The Dencun fork occurred on March 13, 2024, introducing multi-dimensional blob pricing.

Multi-Dimensional Gas and Stateless Clients

In the near future, storage proofs for stateless clients will also face similar issues. Stateless clients are a new type of client that will be able to verify the chain without needing to store a large amount or any data locally. Stateless clients achieve this by accepting proofs of the specific parts of Ethereum state that transactions in that block need to access.

The figure above shows a stateless client receiving a block and proofs of the current values of the state-specific parts (e.g., account balances, code, storage) touched by the execution of that block, allowing nodes to verify a block without any storage.

A storage read costs 2100-2600 Gas, depending on the type of read, and storage write costs even more. On average, a block performs about 1000 storage read and write operations (including ETH balance checks, SSTORE and SLOAD calls, contract code reads, and other operations). However, the theoretical maximum is 30,000,000/2,100=14,285 reads. The bandwidth load of stateless clients is proportional to this number.

The current plan is to support stateless clients by transitioning Ethereum's state tree design from Merkle Patricia trees to Verkle trees. However, Verkle trees do not have post-quantum security and are not the optimal choice for newer STARK proof systems. Therefore, many are interested in supporting stateless clients through binary Merkle trees and STARKs, either completely skipping Verkle or upgrading to it after a few years, once STARKs become more mature.

STARK proofs based on binary hash tree branches have many advantages, but their key weakness is the long time it takes to generate proofs: Verkle trees can prove over 100,000 values per second, while hash-based STARKs typically can only prove a few thousand hashes per second, and proving each value requires including many hash "branches."

Considering the numbers predicted today from highly optimized proof systems like Binius and Plonky3, as well as specialized hashes like Vision-Mark-32, it seems that proving 1000 values per second will be feasible for a while, but proving 14,285 values will not be feasible. The average block will be fine, but potential worst-case blocks (published by attackers) will disrupt the network.

Our default method for handling such situations is to reprice: increase the cost of storage reads to reduce the maximum value per block to a safer level. However, we have done this many times, and if we do it again, it will make too many applications too expensive. A better approach is multi-dimensional Gas: to limit and charge for storage access separately, keeping the average usage at 1,000 storage accesses per block, but setting a limit for each block, for example, 2000 accesses.

Universality of Multi-Dimensional Gas

Another resource worth considering is the growth in state size: the operations that increase the Ethereum state size, which subsequently need to be saved by full nodes. The uniqueness of state size growth is that the reason for limiting it comes entirely from long-term sustained usage, rather than peak usage.

Therefore, adding a separate Gas dimension for operations that increase state size (e.g., zero-to-nonzero SSTORE, contract creation) may be valuable, but with a different goal: we can set a floating price to target a specific average usage, but not set a limit for each block.

This demonstrates a powerful property of multi-dimensional Gas: it allows us to separately ask for each resource (i) what is the ideal average usage? (ii) what is the safe maximum usage per block? Unlike setting Gas prices based on the maximum value per block and letting the average usage follow, we have 2n degrees of freedom to set 2n parameters, adjusting each parameter based on considerations for network security.

In more complex cases, such as when security considerations for two resources partially overlap, this can be handled by making an opcode or resource consumption use multiple types of Gas in some quantity (e.g., a zero-to-nonzero SSTORE might consume 5000 stateless client proof Gas and 20000 storage expansion Gas).

Max (transaction) for each transaction (choose the one that consumes more data or computation)

Let ?1 be the Gas cost for data and ?2 be the Gas cost for computation, so in a one-dimensional Gas system, we can write the Gas cost for a transaction as:

In this scheme, we define the Gas cost for a transaction as:

In other words, transactions are charged not based on data plus computation, but based on which of the two resources it consumes more of. This can easily be extended to cover more dimensions (e.g., ???(…,?3∗???????_??????)).

It should be easy to see how this increases throughput while ensuring security. The theoretical maximum data volume in a block is still GasLIMIT/?1, the same as in a one-dimensional Gas scheme. Similarly, the theoretical maximum computation is GasLIMIT/?2, also the same as in a one-dimensional Gas scheme. However, the Gas cost for any transaction that consumes data and computation will be reduced.

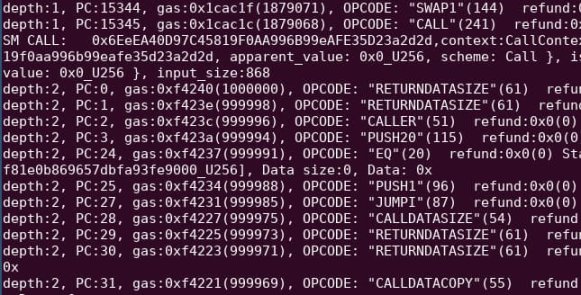

This is probably the approach adopted in the proposed EIP-7623, to reduce the maximum block size while further increasing the blob count. The precise mechanism in EIP-7623 is slightly more complex: it keeps the current calldata price at 16 Gas per byte but adds a floor price of 48 Gas per byte; transactions pay the higher of (16 * bytes + execution_Gas) and (48 * bytes). Therefore, EIP-7623 reduces the theoretical maximum transaction call data in a block from about 1.9 MB to about 0.6 MB, while keeping the cost for most applications unchanged. The benefit of this approach is that it is very easy to implement with minimal changes compared to the current one-dimensional Gas scheme.

However, this approach has two drawbacks:

- Even if all other transactions in a block use very little of that resource, transactions that heavily use one resource will unnecessarily incur a large cost;

- It incentivizes data-intensive and computation-intensive transactions to be bundled together to save costs.

I believe that rules like those in EIP-7623, for both transaction calldata and other resources, can bring significant benefits, even with these drawbacks.

However, if we are willing to invest (significantly more) development effort, a more ideal approach will emerge.

Multi-Dimensional EIP-1559: A More Difficult but Ideal Strategy

Let's first review how regular EIP-1559 works. We will focus on the version introduced for Gas and Blobs in EIP-4844, as it is more mathematically elegant.

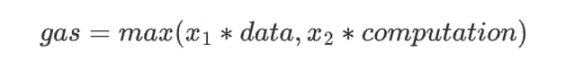

We track a parameter excess_blobs. During each block, we set:

excessblobs -- max(excessblobs + len(block.blobs) - TARGET, 0)

where TARGET = 3. This means that if a block has more blobs than the target, excessblobs will increase, and if a block has fewer blobs than the target, excessblobs will decrease. Then we set blobbasefee = exp(excessblobs / 25.47), where exp is the exponential function ???(?)=2.71828^?.

In other words, every time excessblobs increases by about 25, the blob base fee will increase by about 2.7 times. If blobs become too expensive, the average usage will decrease, and excessblobs will start to decrease, automatically lowering the price again. The price of blobs is continuously adjusted to ensure that, on average, blocks are half full, meaning that each block contains an average of 3 blobs.

If there is a short-term peak in usage, there will be a constraint: each block can contain a maximum of 6 blobs, in which case transactions can compete with each other by increasing the priority fee. However, under normal circumstances, each blob only needs to pay the blob_basefee plus a small additional priority fee to be included.

This type of Gas pricing has been in Ethereum for many years: as early as 2020, EIP-1559 introduced a very similar mechanism. Through EIP-4844, we set two separate floating prices for Gas and Blobs.

Note: Gas base fees within one hour on May 8, 2024, in gwei. Source: ultrasound.money

In principle, we can add more independent floating fees for storage reads and other types of operations, but I will detail an issue to be aware of in the next section.

For users, this experience is very similar to today: you no longer pay a base fee, but instead pay two base fees, but your wallet can abstract this from you and only show you the expected fee and the maximum fee you can expect to pay.

For block builders, the optimal strategy is mostly the same as today: include any valid content. Most blocks are not full—whether in Gas or Blob. A challenging situation is when there is enough Gas or enough Blob to exceed the block limit, and builders potentially need to solve a multi-dimensional knapsack problem to maximize their profit. However, even with fairly good approximation algorithms, the profit gained from optimizing with a proprietary algorithm in this case is much smaller than the profit gained from using MEV for the same operation.

For developers, the main challenge is the need to redesign the functionality of the EVM and its related infrastructure, which is currently designed based on a single price and a single limit, and now needs to be transformed to accommodate multiple prices and multiple limits.

One issue that application developers face is that optimization becomes slightly more difficult: in some cases, you can no longer explicitly say that A is more efficient than B, because if A uses more calldata and B uses more execution, then when calldata is cheap, A may be cheaper, but when calldata is expensive, A may be more expensive.

However, developers can still achieve fairly good results by optimizing based on long-term historical average prices.

Multi-Dimensional Pricing, EVM, and Sub-Calls

There is an issue that does not appear in blobs, and will not appear in a complete multi-dimensional pricing implementation for EIP-7623 or even for pricing state access or any other resource separately, but it will appear if we try to price sub-calls separately for each type of Gas: the Gas limit in sub-calls.

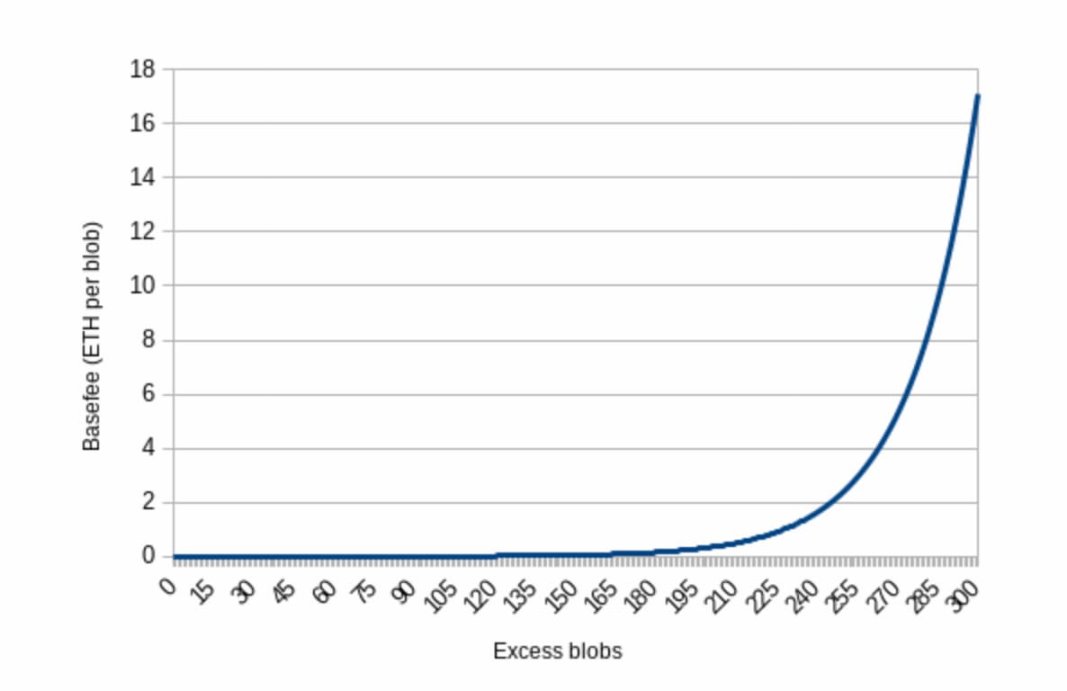

Gas limits in the EVM exist in two places. First, each transaction sets a Gas limit, limiting the total amount of Gas that can be used in that transaction. Second, when a contract calls another contract, the call can set its own Gas limit. This allows contracts to call other contracts they do not trust and still ensure that they have remaining Gas to perform other computations after the call.

Note: The trace of an account abstracting a transaction, where one account calls another and provides a limited amount of Gas to the callee to ensure that even if the callee consumes all the Gas allocated to it, the external call can continue to run.

The challenge is: implementing multi-dimensional Gas between different types of execution seems to require sub-calls to provide multiple limits for each type of Gas, which would require very deep changes to the EVM and would be incompatible with existing applications.

This is one of the reasons why multi-dimensional Gas proposals typically stay at two dimensions: data and execution. Data (whether transaction calldata or blob) is allocated externally to the EVM, so no changes are needed internally to price calldata or blob separately.

We can come up with an "EIP-7623-style solution" to address this issue. This is a simple implementation: during execution, charge 4 times the fee for storage operations; for simplicity, assume each storage operation costs 10,000 Gas. At the end of the transaction, refund min(7500 * storageoperations, executionGas). As a result, after deducting the refund, the user needs to pay the following fees:

executionGas + 10,000 * storageoperations - min(7500 * storageoperations, executionGas)

This equals:

max(executionGas + 2500 * storageoperations, 10,000 * storage_operations)

This reflects the structure of EIP-7623. Another approach is to track storageoperations and executionGas in real-time, and charge 2500 or 10,000 based on how much max(executionGas + 2500 * storageoperations, 10,000 * storage_operations) increases. This avoids transactions needing to over-allocate Gas, which is mainly recovered through refunds.

We do not get fine-grained allowances for sub-calls: sub-calls may consume all the allowance of a transaction for cheap storage operations.

But we do get something fairly good, which is that contracts making sub-calls can set a limit and ensure that once the sub-call is done, the external call still has enough Gas for the necessary post-processing.

The simplest "complete multi-dimensional pricing solution" I can think of is: we treat the Gas limit for sub-calls as proportional. That is, assume there are ? different types of execution, and each transaction sets multi-dimensional limits ?1…?? . Assume at the current execution point, the remaining Gas is ?1…?? . Assume a CALL opcode is called, and the sub-call Gas limit is set to ? . Let ?1=? , then ?2=?1/?1∗?2 , ?3=?1/?1∗?3 , and so on.

In other words, we treat the first type of Gas (actually VM execution) as a special kind of "account unit," and then allocate other types of Gas so that sub-calls get the same percentage of available Gas in each type of Gas. This approach is a bit ugly, but maximizes backward compatibility.

If we want to make this approach more "neutral" between different types of Gas without sacrificing backward compatibility, we can simply represent the sub-call Gas limit parameter as a fraction of the remaining Gas in the current context (e.g., [1…63]/64).

However, in either case, it is worth emphasizing that once we start introducing multi-dimensional execution Gas, inherent complexity (ugliness) will increase, which seems difficult to avoid.

Therefore, our task is to make a complex trade-off: do we accept a certain degree of increased complexity (ugliness) at the EVM level to safely unlock significant L1 scalability gains, and if so, which specific proposal is most effective for the protocol economy and application developers? It is quite likely that neither of the two approaches I mentioned above is the best, but there is still room to propose more elegant and better solutions.

Special thanks to Ansgar Dietrichs, Barnabe Monnot, and Davide Crapis for their feedback and review.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。