Text | Vinko

In 2023, a letter arrived in the mailboxes of one hundred thousand families in Florida, USA.

The letter came from Farmers Insurance, a century-old company in the insurance industry. The content was brief yet cruel: one hundred thousand policies, from homes to cars, were immediately voided.

The promises in black and white turned to waste paper overnight. Furious policyholders flooded social media, questioning this company they had trusted for decades. But all they received was a cold announcement: "We must manage our risk exposures more effectively."

In California, the situation is even worse. Insurance giants like State Farm and Allstate have stopped accepting new homeowners insurance applications, with over 2.8 million existing policies denied renewal.

An unprecedented "insurance retreat" is unfolding in the United States. Once seen as a stabilizer for society, committed to covering all, the insurance industry itself is now engulfed in turmoil.

Why? Let’s take a look at the following data.

Hurricane Helene caused losses in North Carolina that could exceed $53 billion; Hurricane Milton, as estimated by Goldman Sachs, could lead to insurance losses of over $25 billion; while for a major fire in Los Angeles, AccuWeather estimated total economic losses between $250 billion and $275 billion, and CoreLogic estimated insurance payouts to be between $35 billion and $45 billion.

Insurance companies are realizing they are facing the limits of their payout capabilities. So, who can replace the traditional insurance industry?

The Betting Game in the Café

The story begins over three hundred years ago in London.

In 1688, along the Thames River, at a café called Lloyd’s, sailors, merchants, and ship owners were all overshadowed by the same shadow. Cargo-laden merchant ships were setting off from London to distant Americas or Asia. If they returned safely, it meant immense wealth; but if they encountered storms, pirates, or ran aground, they would lose everything.

Risk loomed like a persistent dark cloud over every seafarer’s heart.

Café owner Edward Lloyd was a shrewd businessman. He realized that these captains and cargo owners needed more than coffee; they needed a place to share their risks. Thus, he began to encourage a kind of "betting game."

A captain would write the information about the ship and its cargo on a piece of paper and post it on the café wall. Anyone willing to take on part of that risk could sign their name on this paper and write down the amount they were willing to insure. If the ship returned safely, they would proportionally share in the fee paid by the captain (the premium); if the ship was lost, they would proportionally compensate the captain's losses.

If the ship returns, everyone is happy; if it sinks, everyone shares the loss.

This is the prototype of modern insurance. It lacked complex actuarial models, relying solely on simple business wisdom—sharing an individual's large risk among a group.

In 1774, 79 underwriters united to form the Lloyd’s Association, moving from the café to the Royal Exchange. A trillion-dollar modern financial industry was born.

For over three hundred years, the essence of the insurance industry has never changed: it is a business of managing risk. Through actuarial science, probabilities of various risks are calculated, priced, and then sold to those seeking protection.

But today, this ancient business model faces unprecedented challenges.

When the frequency and intensity of hurricanes, floods, and wildfires far exceed predictions based on historical data and actuarial models, insurance companies find that their measuring stick can no longer quantify the growing uncertainties of this world.

They face only two choices: either significantly raise premiums or, as we see in Florida and California, retreat.

A More Elegant Solution: Risk Hedging

As the insurance industry falls into the predicament of "inability to assess, afford to pay, or dare to insure," we might look beyond insurance and seek answers in another ancient industry: finance.

In 1983, McDonald's planned to launch a revolutionary product: Chicken McNuggets. But a dilemma arose for management; chicken prices fluctuated too much. If they locked in menu prices and chicken prices soared, the company would face huge losses.

The tricky part was that there was no chicken futures market at the time to hedge the risks.

Ray Dalio was a commodity trader at the time, and he offered a genius solution.

He told McDonald's chicken suppliers, "The cost of a chicken is just the chick, corn, and soybean meal, right? Chick prices are relatively stable; it's the prices of corn and soybean meal that are truly volatile. You could buy futures contracts for corn and soybean meal in the futures markets to lock in production costs, and this way, you can provide McDonald's with chicken at fixed prices!"

This concept of "synthetic futures," which seems normal today, was revolutionary at the time. It not only helped McDonald's successfully launch Chicken McNuggets but also paved the way for Ray Dalio to later establish the world’s largest hedge fund—Bridgewater.

Another classic example comes from Southwest Airlines.

In 1993, CFO Gary Kelly began establishing a fuel hedging strategy for the company. From 1998 to 2008, this strategy saved Southwest Airlines around $3.5 billion in fuel costs, equivalent to 83% of the company’s profits during that period.

During the 2008 financial crisis, when oil prices soared to $130 a barrel, Southwest Airlines secured 70% of its fuel through futures contracts at a locked price of $51 a barrel. This made it the only mainstream U.S. airline able to maintain the "free baggage policy."

Whether it’s McDonald's chicken or Southwest Airlines’ fuel, both reveal the same fundamental business wisdom: through financial markets, transforming future uncertainties into present certainties.

This is hedging. It shares the same goals as insurance but operates on fundamentally different logic.

Insurance is about risk transfer. You transfer risks (like accidents, illnesses) to the insurance company and pay a premium for it; hedging is about risk offsetting.

If you have a position in the spot market (like needing to buy fuel), you set up an opposing position in the futures market (like buying fuel futures). When spot prices rise, profits from futures can offset losses in the spot market.

Insurance is a relatively closed system, dominated by insurance companies and actuaries; whereas hedging is an open system, where market participants collectively price risks.

The answer is simple: because there isn’t such a market.

Until a young entrepreneur brought it to us while starting in the bathroom.

From "Risk Transfer" to "Risk Trading"

22-year-old Shayne Coplan founded Polymarket in his bathroom. This blockchain-based prediction market gained fame in 2024 due to the U.S. elections, surpassing $9 billion in annual trading volume.

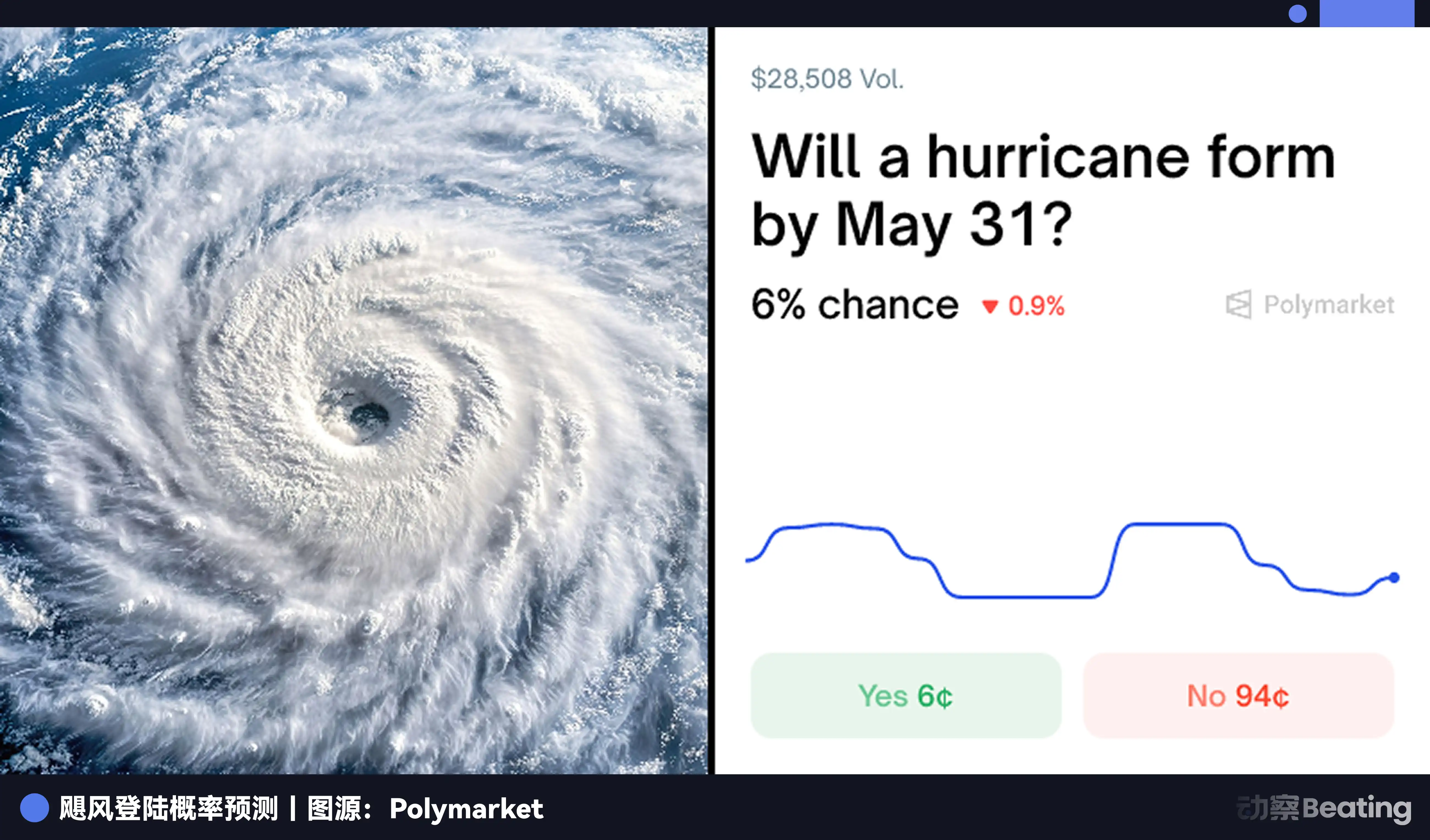

Aside from political bets, Polymarket hosts some intriguing markets. For example, will Houston's highest temperature exceed 105 degrees Fahrenheit in August? Will nitrogen dioxide levels in California exceed average levels this week?

An anonymous trader named Neobrother made over $20,000 by trading these weather contracts on Polymarket. He and his followers are known as "weather hunters."

While insurance companies flee Florida due to unpredictable weather, a group of mysterious players eagerly trades temperature variations of 0.1 degrees Celsius.

Prediction markets are essentially platforms where "everything can be tokenized." They extend the functions of traditional futures markets from standardized commodities (like oil, corn, foreign currency) to any publicly and objectively verifiable event.

This presents a new approach to resolving challenges in the insurance industry.

Firstly, it replaces the arrogance of experts with the wisdom of the crowd.

Traditional insurance pricing relies on the insurance company’s actuarial models. But as the world becomes increasingly unpredictable, models based on historical data become ineffective.

The prices in prediction markets, however, are generated by thousands of participants "voting" with real money. They reflect the market's total information about the probability of an event occurring. The price volatility of a contract regarding "will a hurricane hit Florida in May" itself is the most sensitive and real-time measure of risk.

Secondly, it replaces the helplessness of bearing losses with the freedom of trading.

A resident of Florida concerned about their house being destroyed by a hurricane no longer has just one option of "buying insurance." They can go to the prediction market and buy a contract on "hurricane landfall." If the hurricane does come, the profit from the contract can help cover the expenses of damage to their house.

This represents a personalized risk hedging.

More importantly, they can sell this contract anytime to lock in profits or cut losses. Risk becomes an asset that can be sliced, traded, and bought or sold at will, rather than a heavy burden that needs to be packaged and transferred all at once. They shift from being risk bearers to risk traders.

This is not just a technical improvement; it’s a transformation in thinking. It liberates the pricing power of risk from the hands of a few elite institutions and returns it to everyone.

The End of Insurance or a New Beginning?

Will the prediction market, this "universal risk trading platform," replace insurance?

On one hand, prediction markets are undermining the foundation of the traditional insurance industry in a profound way.

The core of traditional insurance is information asymmetry. Insurance companies have actuaries and vast data models, and they must understand risks better than you to price them. But when the pricing power of risk is replaced by a market that is open, transparent, driven by collective wisdom and even insider information, the information advantage of insurance companies disappears.

Residents of Florida no longer need to blindly trust the quotes of insurance companies; they can simply glance at the price of hurricane contracts on Polymarket to know the market's real judgment of risk.

More critically, traditional insurance is a "heavy model" — sales, underwriting, claims adjustment, payouts... each link is filled with human costs and friction; while the prediction market is an extreme "light model," with only trade and settlement, and almost zero intermediaries.

On the other hand, we see that prediction markets are not a panacea; they cannot completely replace insurance.

They can only hedge risks that are clearly defined and publicly verifiable (such as weather, election results). For more complex and subjective risks (like accidents caused by driving behavior or personal health conditions), they fall short.

You cannot open a contract on Polymarket asking the world to predict "will you get into a car accident next year."

Personalized risk assessment and management remain the core advantage of traditional insurance.

The future landscape may not be a battle of "who replaces whom," but a new and sophisticated relationship of competition and cooperation.

Prediction markets will become the infrastructure for risk pricing. Just as today's Bloomberg Terminal and Reuters serve as foundational data anchors for the financial world, insurance companies may also become deeply involved in prediction markets, using market prices to calibrate their models or hedge catastrophic risks they cannot manage.

Insurance companies will return to the essence of service.

When pricing advantages disappear, insurance companies must rethink their value. Their core competitiveness will no longer be information asymmetry but rather a focus on areas requiring deep intervention, personalized management, and long-term service, such as health management, retirement planning, and wealth inheritance.

The giants of the old world are learning the steps of the new world, while the explorers of the new world need to find routes back to the old world continents.

Conclusion

Over three hundred years ago, in a London café, a group of merchants invented a mechanism for sharing risks with the most primitive wisdom.

Three hundred years later, in the digital world, players are reshaping the way we interact with risk.

History always completes its cycles unexpectedly.

From forced trust to free trading. This may be yet another exciting moment in financial history. Each of us will evolve from passive risk acceptors to active risk managers.

And this concerns not only insurance but also how each of us can better survive in this uncertain world.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。