Text | Sleepy.txt

When a city uses the rules of yesterday to greet the innovations of tomorrow, it is destined to be lost today.

Today's Hong Kong is shrouded in a sense of enormous fragmentation. Or perhaps it is more like two parallel Hong Kongs, folded into the same city.

One Hong Kong, in the skyscrapers of Central.

In 2025, Hong Kong's economy performed strongly, with the annual GDP real growth expected to reach 3.2%. The Hang Seng Index rose by 27.8%, marking the best annual performance since 2017. The value of goods exports hit a record high, with December's monthly export value reaching HK$512.8 billion, a year-on-year increase of 26.1%. Net capital inflow remained strong, with private wealth management scale exceeding HK$10 trillion.

Here, the sound of champagne bubbles is everlasting, and prosperity is the only theme.

The other Hong Kong, in shared office spaces in Cyberport, on the streets of Sham Shui Po, at the crowded Lok Ma Chau border crossing.

Entrepreneurs are struggling with high costs; shop closures occur frequently in some sectors like retail; the unemployment rate shows a gradual upward trend in 2025; and more and more Hong Kong residents choose to abandon the once "shopping paradise" to shop in Shenzhen and Guangzhou.

Here, disappointment and confusion are the unshakable background noise in the air.

On one side is the fiery cooking of financial data, on the other is the thin ice of public sentiment. This extreme contradiction is the most honest reflection of Hong Kong today. Hong Kong is living off its past, trying to use yesterday's experiences to cope with today's changes, and the results are evident.

Two Crises and Muscle Memory

The rules that Hong Kong follows today are the result of two painful lessons: the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the global financial tsunami in 2008. These two crises left Hong Kong severely wounded and scared. They even formed a muscle memory, where the first reaction to any risk is to retract.

In 1997, shortly after Hong Kong's return, international speculators led by Soros's Quantum Fund targeted this juicy asset, shorting the Hong Kong dollar with one hand and shorting Hong Kong stocks with the other, intending to crush the currency regime. A fierce battle known as the "Hong Kong Financial Defense War" ensued.

The then Financial Secretary, John Tsang, later recalled that it was a suffocating period. The Soroses laid a intricate trap through short selling and borrowing, creating a chain reaction in the stock and foreign exchange markets. They first dumped the Hong Kong dollar heavily in the foreign exchange market, forcing the Hong Kong Monetary Authority to raise interest rates to maintain currency stability. High interest rates inevitably led to stock market declines, which allowed them to close their massive short positions at a profit. The net was cast, and both the stock and foreign exchange markets became their dual ATMs.

Faced with this assault, the Hong Kong government initially retreated step by step. But on August 14, 1998, the government decided to use foreign exchange reserves for direct market intervention. Over the next ten trading days, the government invested a total of HK$118 billion (about US$15 billion) to confront the international speculators head-on.

On August 28, during the futures settlement day for the Hang Seng Index, the turnover reached an all-time high of HK$79 billion, and the government steadfastly defended 7829 points, ultimately forcing the speculators to settle at a high price and return empty-handed.

Although this victory was bitter, it preserved the linked exchange rate, Hong Kong's financial lifeline. However, since then, Hong Kong has left a legacy; regulators established an iron law: stability is above all. Any factor that may pose a potential threat to financial stability must be examined under the strictest scrutiny.

This is the first layer of muscle memory in Hong Kong.

If the crisis in 1997 was merely an external shock, then the 2008 crisis was a wildfire in its own backyard. Although the fire originated from the United States, what it ultimately burned down was the trust of ordinary Hong Kong citizens in the elites of Central.

That year, the collapse of Lehman Brothers across the ocean sent shockwaves like a tsunami crashing onto Hong Kong. Over 40,000 Hong Kong citizens, the vast majority of whom were elderly living on pensions, found their mini bonds linked to Lehman Brothers suddenly worthless overnight.

These mini bonds, packaged as low-risk, high-yield investment products, were sold through bank channels to ordinary people who lacked risk tolerance. This incident exposed regulatory loopholes and sales misguidance within Hong Kong's financial system, severely undermining public trust in financial institutions.

This incident also directly led to stricter investor protection regulations and more complex financial product sales procedures in Hong Kong. Regulators adopted an almost obsessive attitude toward any financial innovations that could trigger systemic risk, especially those that might harm the interests of ordinary investors.

This is the second layer of muscle memory in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong’s financial regulatory system underwent a complete transformation into one that heavily emphasizes stability and safety only after experiencing these two crises. This path dependence has enabled Hong Kong to successfully withstand numerous external shocks over the past twenty years but has made it feel out of place and even unfit when facing an entirely new wave of financial technology innovation characterized by disruption and decentralization.

So, what kind of fragmented economic reality has this muscle memory rooted in historical trauma given rise to in today’s Hong Kong?

Divided Hong Kong: Whose Prosperity? Whose Disappointment?

The scars of history have dragged three significant rifts across Hong Kong's landscape. Today, Hong Kong finds itself in a state of comprehensive economic fragmentation.

The first rift is between finance and the real economy.

While global capital brokers and investment bankers celebrate Hong Kong's return to the top of the global IPO fundraising charts, the city's real economy is enduring a long winter.

According to data from the Hong Kong Bankruptcy Management Office, the number of company liquidation petitions submitted in 2024 reached 589, a new high since the SARS outbreak in 2003. In just one year, over 500 shops quietly shut down, including local old brands like CR Vanguard and Dah Chong Hong, which have accompanied generations of Hongkongers. The once-coveted locations in Causeway Bay and Tsim Sha Tsui are now lined with closed shop shutters and rental advertisements.

The decline of the real economy is directly reflected in the job market. Hong Kong's overall unemployment rate has mostly stayed around 3% throughout 2025, while the unemployment rates in sectors like retail, accommodation, and food services are far above the average. The youth unemployment rate among those aged 20 to 29 remains alarmingly high. On one side, there are abundant job ads in finance with record bonuses for traders; on the other, the retail industry faces ongoing layoffs, leaving ordinary citizens' jobs precarious.

Prosperity has never been so concentrated; disappointment has never been so widespread.

The second rift is between elites and the public.

If the gap between finance and the real economy depicts an industry facing two extremes, then the gap between elites and the public reveals a chasm of alienation. This alienation is most vividly reflected in the flow of money and people.

On one side, global billionaires and mainland elites vote with their money and pour into Hong Kong.

In 2024, Hong Kong's asset and wealth management business recorded a net inflow of HK$705 billion, reaching an all-time high. The total transaction value and number of transactions from mainland buyers in Hong Kong's real estate market surged nearly tenfold, purchasing residential properties worth HK$138 billion in a year. Transactions of luxury homes worth over HK$100 million were booming, seemingly unaffected by economic cycles.

On the other side, ordinary Hong Kong citizens are voting with their feet and heading north to mainland China.

In 2024, the total number of Hong Kong residents traveling north reached 77 million, spending nearly HK$55.7 billion in the mainland, from dining out and having a cup of milk tea to seeing dentists and receiving services. Shenzhen and Zhuhai have become the preferred weekend destinations for Hongkongers.

Deeper demographic movements are reflected in cross-border marriages, education, and elderly care.

According to data from the Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department, the proportion of "Hong Kong women marrying north" surged from 6.1% in 1991 to 40% in 2024; more than 30,000 cross-border schoolchildren travel between Hong Kong and Shenzhen daily; nearly 100,000 elderly Hongkongers choose to retire in Guangdong, enjoying lower living costs and more spacious living environments.

When the elites of a city discuss the globalization of asset allocation, its citizens are pondering where to buy a cheaper meal in Shenzhen. On one side is the glorious afterglow of an imperial dynasty of finance, and on the other side is a stagnant baseline.

The third rift is between assets and innovation.

Hong Kong has never lacked money, but it seems that money does not flow to where it is needed the most.

Hong Kong's research and development intensity, defined as R&D spending as a percentage of GDP, hovers around 1.13% year after year. This number is less than half of Singapore's and even just a quarter of South Korea's. Even more alarming, Shenzhen, just across the river, has already surpassed the 5% threshold in R&D intensity.

Although the number of start-up companies in Hong Kong reached 4,694 in 2024, a year-on-year increase of 10%, the average scale was only 3.8 people, reflecting a situation of many small plants but no large trees.

Capital prefers to chase high-certainty assets, such as real estate and stocks, rather than the high-risk, long-return cycles of technological innovations. The high costs of housing and rent have also greatly squeezed the survival space for start-up companies. In Hong Kong, a young entrepreneur's biggest headache is often not finding a good direction, but being unable to afford next month's office rent.

The rift between finance and the real economy, between elites and the public, between assets and innovation, together paints a bizarre picture of Hong Kong's economy. It resembles the character of Mordor from the Marvel universe, with the head (finance) excessively developed, while the trunk and limbs (real economy, innovation) are withering.

So, in such a soil, how will the seed of financial innovation take root and sprout? Will it transform this soil, or will it be transformed by it?

Financial Innovation with No Winners

The answer is that it has been transformed by this soil. Hong Kong's financial technology innovation has always been a strictly controlled, top-down reform movement.

Here, you cannot tame the flame and expect it to illuminate the dark.

The first battlefield of this reform movement is payment.

Once upon a time, a small Octopus card was a proud innovation for Hongkongers. But as mobile payment swept the globe, the Octopus card reacted slowly, giving mainland payment giants and local innovators a huge opportunity to imagine.

However, in the end, the unified battlefield was not WeChat Pay or Alipay, nor any ambitious start-up, but two products with strong "official" and "establishment" characteristics: HSBC's PayMe and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority's Fast Payment System (FPS).

PayMe was born with a golden key, backed by HSBC, Hong Kong's largest note-issuing bank, with a vast existing customer base and unparalleled brand trust. Meanwhile, FPS was built by the regulatory authority as a cross-bank payment infrastructure.

Their victory is less a victory of the product than a victory of "order." This so-called payment war was never a fair competition. Traditional financial giants and regulators successfully kept other innovators at bay by proactively launching improved products, solidifying their own positions.

If innovation in the payment sector was domesticated from the start, then virtual banks were expected to become "catfish."

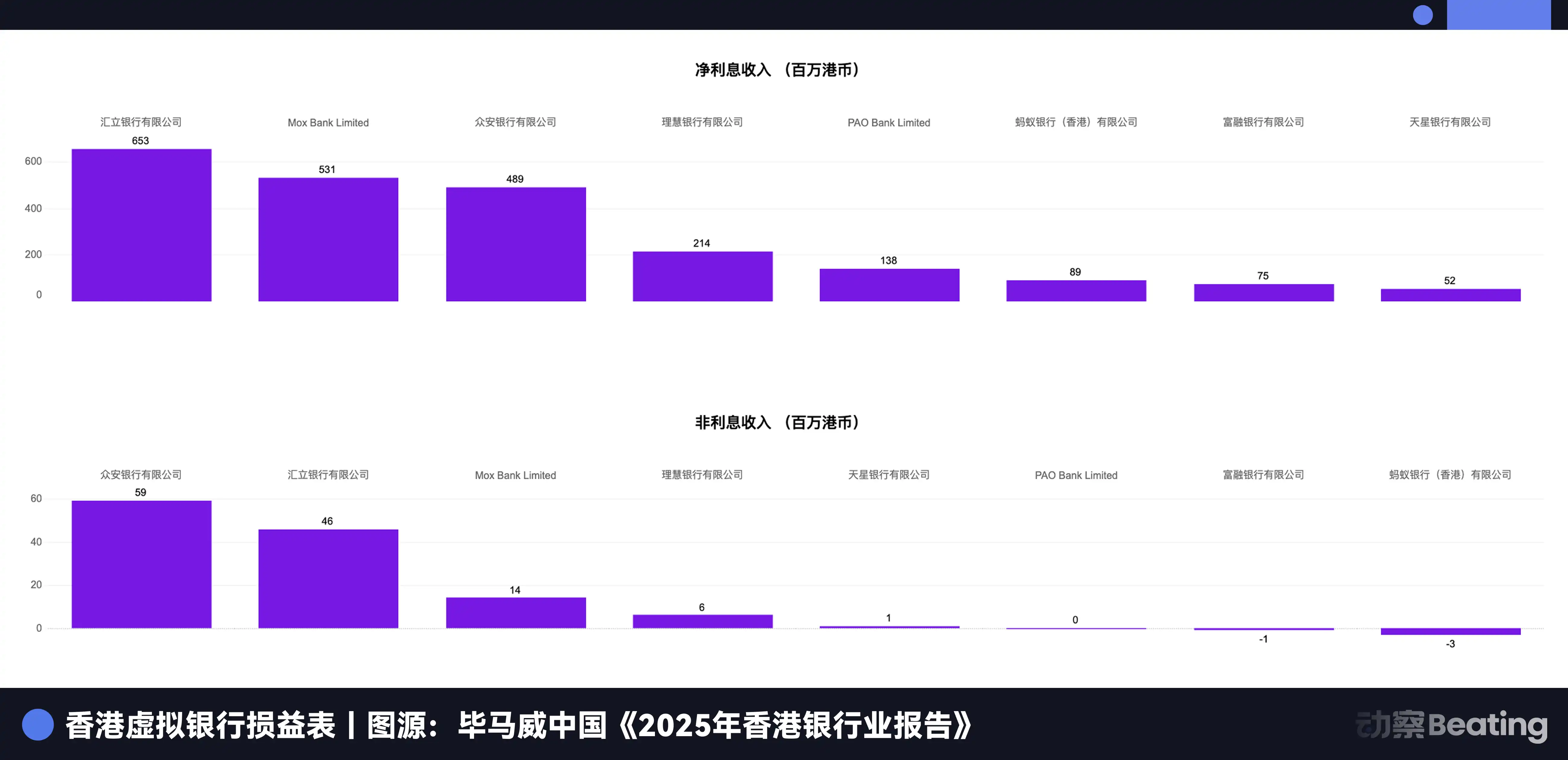

In 2019, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority issued eight virtual banking licenses in one go, hoping to introduce these catfish to stir the stagnant traditional banking sector. However, five years later, the eight virtual banks collectively burned over HK$10 billion, only to capture less than 0.3% of the market share.

By the first half of 2025, three banks—ZhongAn Bank, Livi Bank, and WeLab Bank—finally recorded profits, but the cumulative losses of the eight still reached HK$610 million. The vast majority of Hong Kong citizens still regard traditional banks as their main accounts, while virtual banks are seen more as occasional tools for transfers or promotions.

They have not disrupted anything; instead, they have found themselves in survival dilemmas. The few virtual banks that achieved profitability did so not through disruptive innovation in products or services but by venturing into gray areas traditional banks were hesitant to touch, such as providing account services for Web3 companies.

This is less a victory for the "catfish" than a compromised subjugation. They ended up not becoming challengers but patches in the existing financial system.

More intriguing phenomena occurred in the fields of wealth technology and insurtech.

These two areas are identified by the Monetary Authority as having the greatest growth potential and deserving support because they perfectly align with Hong Kong's core interests, consolidating its position as a global asset management center. Wealth technology makes asset management for high-net-worth clients more convenient, while insurtech makes sales of insurance products more efficient. They are secure innovations serving the existing order and tools that add a touch of icing on the cake.

Thus, we see the "selective prosperity" of Hong Kong’s financial technology. On one side are the asset management scales breaking through HK$35 trillion, while on the other side, virtual banks struggle with only 0.3% market share. Financial technology serving the wealthy has green lights all the way, while that trying to serve the masses or change the landscape runs into walls everywhere.

From payment, banking to wealth management, Hong Kong's financial technology innovation presents a clear pattern: embracing reform, resisting innovation.

This ultimately evolves into a war without winners. Traditional giants may have retained their moats, but they may have also lost the impetus for more thorough and forward-looking innovations; while passionate innovators, after paying a heavy price, have not managed to truly change the game rules of this market.

If even in relatively mature financial technology areas like payment and banking, Hong Kong chooses such a conservative path of subjugation, then how will it choose when faced with a truly wild, unpredictable innovation like Web3, with decentralization as its core?

The Hong Kong-style Embarrassment of Web3

If Hong Kong's approach to financial technology is subjugation, then its attitude toward Web3 is another kind of dilemma: embracing its form, rejecting its essence.

At the end of 2022, Hong Kong boldly announced its ambition to become a global virtual asset hub, and in a flash, policy proclamations flooded in, from the admission of retail investors to regulatory sandboxes for stablecoins, portraying a posture of embracing the future. However, more than two years later, what we have waited for is a typical Hong Kong-style embarrassment.

In April 2024, when Hong Kong launched Asia's first batch of virtual asset spot ETFs ahead of the United States, the entire market buzzed with excitement. However, the honeymoon was as brief as a summer rain. By the end of 2025, the total assets under management of the six virtual asset ETFs in Hong Kong amounted to just US$529 million, more than 80 times less than the US total of over US$45.7 billion.

Both are ETFs with the same assets, yet one is grown in the south and the other in the north; unfortunately, Hong Kong is in the north.

An even deeper layer of embarrassment lies beneath the compliance stranglehold. Hong Kong has set one of the strictest regulatory standards in the world for virtual asset trading platforms, which certainly mitigates the risk of collapses like FTX, but it also brings extremely high compliance costs.

Industry insiders reveal that a licensed virtual asset trading platform in Hong Kong faces monthly operating costs of up to US$10 million, with 30% to 40% of that going toward compliance, legal, and auditing. This is manageable for giants, but for the vast majority of small and medium start-up teams, it is like an insurmountable chasm.

The JPEX incident in 2023 further pushed this embarrassment to the extreme. This unlicensed trading platform attracted a large number of ordinary citizens with aggressive online and offline marketing, offering "zero risk, high yield" as bait, ultimately collapsing with involved amounts reaching HK$1.6 billion.

The negative impact of the JPEX incident is that it created an effect of bad money driving out good on a societal level, causing ordinary people to develop a significant distrust of the entire Web3 industry and making regulatory bodies more determined to adopt strict safeguards.

Thus, a bizarre cycle has formed. The more absolute safety is pursued, the higher the regulatory costs; the higher the regulatory costs, the harder it is for licensed institutions to compete with "wild platforms" operating outside regulation; when "wild platforms" collapse, it further reinforces the necessity for absolute safety.

Hong Kong attempted to build a solid safety house for Web3 but found that when the house was ready, participants in the innovation either chose to start their own fire outside or suffocated inside due to cumbersome rules.

At this point, Hong Kong's true attitude toward Web3 has been revealed. It welcomes cryptocurrency as an alternative asset that can be incorporated into the existing financial system, which can be valued, traded, and managed as a financial product. But it rejects, or rather fears, cryptocurrency as an innovative tool, the kind with decentralization, censorship resistance, and the core spirit of disruption of intermediaries Web3 represents.

The former can add a new segment to Hong Kong's asset management landscape, while the latter may shake the very foundations of the entire landscape.

This reflects the most fundamental conflict between "yesterday's rules" and "tomorrow's innovation." Hong Kong attempts to manage a new species using the logic of managing stocks, bonds, and real estate. As a result, it rejects the innovation itself, leaving only a one-sided policy monodrama with no audience.

The Turning of the Giant Ship

Looking back on Hong Kong's financial technology journey is akin to observing the difficult turn of a giant ship.

This ship named Hong Kong is undoubtedly one of the most successful vessels in the world over the past half century. However, financial innovation does not bring a storm but rather a lowering of sea levels and the rising of new continents. It has exposed countless narrow, twisted, and reef-filled new navigation routes in what was once an unfathomable ocean.

In these new navigation routes, the advantages of the giant ship have turned into its most fatal disadvantages. It is too large to turn around in narrow channels; it is too heavy to navigate in shallow waters; its navigation systems have completely failed in this new hydrological environment.

There is a concept in economics called "the curse of the winner." It refers to the phenomenon where past immense successes create a strong path dependency and mental framework, making it impossible to adapt to an entirely new paradigm and ultimately be bitten back by one's previous success. This may be the most precise summary of Hong Kong's current predicament.

Hong Kong's loss lies not in what it did wrong, but in repeating what it did right in the wrong time. It tries to embrace a flowing feast by building fortresses; it tries to embrace an innovation aimed at demolishing and rebuilding by refining old systems.

Today, this giant ship is docked in the middle of Victoria Harbour, its engine still roaring, but the captain and crew are deeply confused. On the distant sea surface, countless agile speedboats are racing along the new navigation routes, leaving it far behind.

History has never granted any city eternal immunity. When yesterday's glory becomes today's shackles, only the courage to break free can win tomorrow.

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。