作者:Thejaswini M A

编译:Block unicorn

前言

加州理工学院的面试官身体前倾,提出了一个有趣的问题。

「假设我给你无限的资源、无限的人才和 30 年的时间。你像隐士一样把自己锁在实验室里。30 年后,你出来告诉我你发明了什么。你会创造什么?」

当时正在申请教职的博士后研究员卡南,圭迪工程学院攻读本科学位,并参与了印度第一颗学生设计的微型卫星 ANUSAT 的研发。这个项目让他对复杂系统和协调问题产生了兴趣。

2008 年,他带着仅 40 美元的资金来到美国。他在班加罗尔的印度科学研究所攻读电信工程,随后在伊利诺伊大学厄巴纳-香槟分校获得了数学硕士和电气与计算机工程博士学位。

他的博士研究专注于网络信息理论,即信息如何通过节点网络流动。他花了六年时间解决该领域长期未决的难题。当他最终攻克这些问题时,只有他所在子领域的二十个人注意到了。其他人无人问津。

失望引发了一场反思。他一直在追求好奇心和智力之美,而非影响力。如果你不刻意追求,就不能指望现实世界的改变会像副产品一样随机出现。

他画了一二维图。X 轴代表技术深度,Y 轴代表影响力。他的工作稳稳地落在了深度高、影响力低的象限。是时候继续前进了。

2012 年,他参加了一场由人类基因组计划创始人之一克雷格·文特尔主讲的合成基因组学讲座。这个领域正在创造新物种,讨论制造生物机器人而非机械机器人。为什么要浪费时间优化下载速度,当你可以重新编程生命本身?

他完全转向了计算基因组学,在伯克利和斯坦福的博士后研究期间专注于此。他研究了 DNA 测序算法,构建数学模型以理解基因结构。

然后,人工智能让他措手不及。一名学生提议使用 AI 解决 DNA 测序问题。卡南拒绝了。他精心设计的数学模型怎么可能被神经网络超越?学生还是建了这个模型。两周后,AI 碾压了卡南的最佳基准。

这传递了一个信息:十年内,AI 将取代他所有的数学算法。他职业生涯所依赖的一切都将过时。

他面临选择:深入 AI 驱动的生物学,还是尝试新方向。最后,他选择了新的。

从水牛城到地球

加州理工学院的问题一直困扰着他。不是因为他答不出来,而是因为他以前从未这样想过。大多数人都是循序渐进地工作。你拥有 X 项能力,你试图构建 X 项加增量。在已有的基础上进行小幅改进。

30 年的问题要求完全不同的思考。它要求我们想象一个目的地,而不必担心路径。

2014 年,卡南作为助理教授加入华盛顿大学后,制定了他的第一个 30 年项目:解码信息如何存储在生命系统中。他召集了合作者,取得了进展。一切似乎都在正轨上。

然后在 2017 年,他的博士导师打来电话,谈到比特币。它有吞吐量和延迟问题——这正是卡南在博士期间研究的内容。

他的第一反应是?他为什么要为了「胡乱猜测的胡扯」而放弃基因组学?

技术契合度很明显,但这似乎与他宏大的愿景相去甚远。然后他重读了尤瓦尔·诺亚·哈拉里的《人类简史》。一个观点让他印象深刻:人类之所以特别,不是因为我们创新或聪明,而是因为我们能够大规模协调。

协调需要信任。互联网连接了数十亿人,但留下了一个缺口。它让我们能够跨大陆即时通信,但却没有提供任何机制来确保人们会信守承诺。电子邮件可以在毫秒内传递承诺,但执行这些承诺仍需律师、合同和集中式机构。

区块链填补了这一缺口。它们不仅仅是数据库或数字货币,而是将承诺转化为代码的执行引擎。陌生人第一次可以在不依赖银行、政府或平台的情况下达成具有约束力的协议。代码本身就让人承担责任。

这成为了卡南新的 30 年目标:构建人类的协调引擎。

但在这里,坎南学到了许多学者常常忽略的一点。拥有 30 年的愿景并不意味着你能直接跳到 30 年。你必须赢得优势,才能解决更大的问题。

移动地球所需的能量比移动一头水牛多一百万倍。如果你想最终移动地球,你不能只是宣布这个目标,然后指望获得资源。根据坎南的说法,你必须先移动一头水牛。然后可能是一辆车。然后是一栋建筑。然后是一座城市。每一次成功都会为你带来更大的筹码,以应对下一次挑战。

世界这样设计是有原因的。给一个从未移动过水牛的人移动地球的权力,整个世界都可能爆炸。渐进式杠杆可以防止灾难性的失败。

卡南第一次尝试移动水牛的项目是 Trifecta。这是他和另外两位教授共同打造的一条高吞吐量区块链。他们提出了一个每秒 10 万笔交易的区块链方案。但没有人为其提供资金。

为什么?因为没人需要它。团队优化了技术,却没有理解市场激励或明确客户。他们雇佣了思维方式相同的人——都是解决理论问题的博士。

Trifecta 失败了。卡南回到了学术和研究领域。

然后他再次尝试,创建了一个名为 Arctics 的 NFT 市场。他曾是 Dapper Labs(运营 NBA Top Shot)的顾问。NFT 领域看似很有前景。但在构建市场时,他不断遇到基础设施的问题。如何为 NFT 获取可靠的价格预言机?如何在不同链之间桥接 NFT?如何运行不同的执行环境?

这个市场也失败了。他不了解 NFT 交易者的思维。如果你不是自己的客户,你就无法构建出有意义的产品。

每个问题都需要同一个东西:一个信任网络。

他应该构建一个预言机?一个桥?还是应该构建解决所有这些问题的元事物——信任网络本身?

这点他明白了。他正是那种会构建预言机或桥的人。他可以成为自己的客户。

2021 年 7 月,卡南创立了 Eigen Labs。名字来自德语「自己的」,意为任何人都可以构建他们想要的东西。其核心理念是通过共享安全实现开放创新。

技术创新是「再质押」。以太坊验证者锁定 ETH 来保护网络。如果他们能同时使用这些资产来保护其他协议呢?新的区块链或服务无需从头构建自己的安全机制,而是可以借用以太坊已建立的验证者集。

卡南向 a16z 提出了五次这个想法才获得资助。一次早期的推介会因为错误的原因而令人难忘。卡南想基于 Cardano 构建,因为它有 800 亿美元的市值但没有可用的智能合约。a16z 的合伙人从 Solana 会议外接听了电话。他们的反应是:这很有趣。你为什么选 Cardano?

反馈迫使卡南思考专注度。初创企业是指数级游戏。你希望将线性工作转化为指数级影响。如果你认为自己有三个指数级想法,你可能一个也没有。你需要选择指数最高的那一个,并全力以赴。

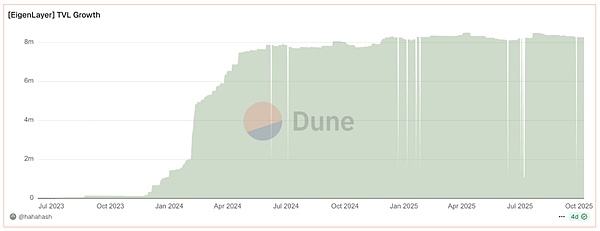

他重新聚焦于以太坊。这个决定被证明是正确的。到 2023 年,EigenLayer 从包括 Andreessen Horowitz 在内的公司筹集了超过 1 亿美元。协议分阶段推出,最高时锁定总价值达到 200 亿美元。

开发者开始在 EigenLayer 上构建「主动验证服务」(AVS),从数据可用性层到 AI 推理网络,每一个都可以利用以太坊的安全池,而无需从头开始构建验证器。

然而,成功也带来了审查。2024 年 4 月,EigenLayer 宣布了其 EIGEN 代币分发,随后引发了强烈反响。

空投将代币锁定了数月,阻止接收者出售。地理限制排除了美国、加拿大、中国等司法管辖区的用户。许多早期参与者(存入数十亿美元)认为这种分配方式偏向内部人士而非社区成员。

这一反应让卡南措手不及。协议的总锁定价值暴跌 3.51 亿美元,用户撤资以示抗议。这场争议暴露了卡南的学术思维与加密世界期望之间的差距。

随后是利益冲突丑闻。2024 年 8 月,CoinDesk 报道称,Eigen Labs 员工从基于 EigenLayer 的项目中获得了近 500 万美元的空投。员工集体从 EtherFi、Renzo 和 Altlayer 等项目中认领了数十万代币。至少有一个项目迫于压力,将员工纳入其分配范围。

这一揭露引发了指控,认为 EigenLayer 正在损害其「可信中立」的立场,利用影响力奖励向员工提供代币的项目。

Eigen Labs 通过禁止生态系统项目向员工空投并实施禁售期来回应。但其声誉已受损。

尽管存在这些争议,EigenLayer 仍处于以太坊演变的核心。该协议已与谷歌云和 Coinbase 等主要参与者建立了合作伙伴关系,后者担任节点运营商。

卡南的愿景远超再质押。「加密是我们协调的超级高速公路,」他说。「区块链是承诺引擎。它们让你能够做出并遵守承诺。」

他从数量、多样性和可验证性三个方面思考。人类可以做出并遵守多少承诺?这些承诺可以有多多样化?我们能多容易地验证它们?

「这是一个疯狂的、百年项目,」卡南说。「它将升级人类物种。」

协议推出了 EigenDA,一个设计用于处理所有区块链总吞吐量的数据可用性系统。团队引入了主观性治理机制,用于解决无法仅在链上验证的争议。

但卡南承认工作远未完成。「除非你能在链上运行教育、医疗,否则工作不算完成。我们还远未完成。」

他的构建方法结合了自上而下的愿景与自下而上的执行。你需要知道目标山在哪里。但你也需要找到从你今天站立的地方通往那里的坡度。

「如果你今天无法用你的长期愿景做任何事,那它也没用,」他解释道。

可验证云是 EigenLayer 的下一个前沿。传统云服务需要信任亚马逊、谷歌或微软。卡南的版本让任何人运行云服务——存储、计算、AI 推理——并通过加密证明它们正确执行。验证者对他们的诚实下注。恶意行为者将失去他们的质押。

40 多岁的卡南在华盛顿大学保持着附属教授的身份,同时运营 Eigen Labs。他仍然发表研究,仍然从信息理论和分布式系统的角度思考。

但他不再是那个无法回答加州理工 30 年问题的学者。他现在已经回答了三次——基因组学、区块链、协调引擎。每次回答都建立在前一次尝试的经验教训之上。

水牛已被移走。汽车已开启。建筑也开始移动。他最终是否能移动地球还有待观察。但卡南明白了一件许多学者从未学会的事情:解决大问题的路径始于解决小问题,并积累解决更大问题的筹码。

免责声明:本文章仅代表作者个人观点,不代表本平台的立场和观点。本文章仅供信息分享,不构成对任何人的任何投资建议。用户与作者之间的任何争议,与本平台无关。如网页中刊载的文章或图片涉及侵权,请提供相关的权利证明和身份证明发送邮件到support@aicoin.com,本平台相关工作人员将会进行核查。